Canada: Who Do We Think We Are? is a new exhibition by Library and Archives Canada (LAC) marking the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation. This exhibition is accompanied by a year-long blog series.

Canada: Who Do We Think We Are? is a new exhibition by Library and Archives Canada (LAC) marking the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation. This exhibition is accompanied by a year-long blog series.

Join us every month in 2017! Experts from LAC, from across Canada and from other countries provide additional information about the exhibition. Each “guest curator” discusses one item, then adds another to the exhibition—virtually.

Be sure to visit Canada: Who Do We Think We Are? at 395 Wellington Street, Ottawa, from June 5, 2017, to March 1, 2018. Admission is free.

Carte géographique de la Nouvelle Franse faictte par le sieur de Champlain, 1612

Carte geographique de la Nouvelle Franse faictte par le sieur de Champlain [map of New France made by Samuel de Champlain], from the book Les voyages du sieur de Champlain…, 1613, engraved by David Pelletier in 1612 (MIKAN 3919638) (AMICUS 4700723)

Explorer Samuel de Champlain saw Canada as a land of potential. He published this book, with an eye-catching map, to advertise its possibilities to investors. The beautiful drawings of plants are probably his own.

Tell us about yourself

I’ll do that by telling you about the documents for which I’m responsible and how they inspire me. Early maps are a gold mine of historical information. They are also both art and science. I can’t look at them dispassionately, because they reveal so much about their makers: the way they saw the world, their ambitions, how they lived their lives, their relationships with the powers that commissioned their maps or sponsored their voyages (when they were explorers as well), how they obtained previously unknown information about various territories, and so on. It’s hard for us to imagine just how much human and financial effort was required to find new geographic information. People lost their lives trying to advance knowledge. And the individuals who came to possess these extraordinary documents are also exciting subjects. I often think of the François Girard film The Red Violin, which tells the stories, across three centuries, of the people who owned an unusual violin. Similarly, one could follow the work of a 16th-century cartographer, from the so-called Dieppe school, for example, such as Pierre Desceliers, who was always on the lookout for the latest discoveries about the New World. The literature on the history of Canadian and North American cartography is quite extensive, but there are still so many things to discover, and other things that will unfortunately never be recovered. And that’s where imagination comes in. Speaking of imagination, I truly enjoyed reading Dominique Fortier’s novel Du bon usage des étoiles, which created a whole world based on John Franklin’s last, ill-fated expedition. With the recent discovery of the wrecks of Terror and Erebus, reality and fiction blend together.

Is there anything else about this item that you feel Canadians should know?

I could say so many things about this map.

Maps like these are very rare. It’s the only copy that LAC has, and is still attached to the very end of Les voyages, a book published by Champlain in Paris in 1613, with its original binding. Copies of the map may also have been distributed separately. The map was engraved on a copper plate by engraver David Pelletier, probably in 1612, then printed on two sheets that were joined together. The paper also has its story: the watermarks, drawings that are visible when the paper is placed on a light table, are the paper manufacturer’s trademark. They may help to authenticate a document and, since their positioning varies from one document to another, they make each document unique. The watermark on this map is bunches of grapes and, in a cartouche, the manufacturer’s monogram, “A.I.R.,” which we cannot identify with certainty.

This was Champlain’s first large map of North America. Intended for navigators, the map shows his explorations from 1603 to 1611. It also bears the royal coat of arms of France. Champlain had a special relationship with King Henry IV, who was assassinated in 1610.

In the world of discoveries and map-making of his time, Champlain was exceptional: one of the few cartographers who actually explored much of the territory that he showed on his maps. Most cartographers then were not explorers; they worked from maps or accounts provided by others. Champlain travelled with Indigenous people, who were his guides. He recognized their deep knowledge of their territory, questioned them about geography, asked them to draw maps, and incorporated that information into his own maps. He seems to have been the first European to take that approach. In this map, for example, Lake Ontario and Niagara Falls are based on information provided by Indigenous people. Champlain did not actually see Lake Ontario until 1615. He also included information from other European cartographers, particularly for the depiction of Newfoundland. Champlain’s work was frequently copied in turn.

Lake Ontario and Niagara Falls (“sault de eau” [waterfall]) (MIKAN 3919638)

“Chaousarou” (longnose gar) (MIKAN 3919638)

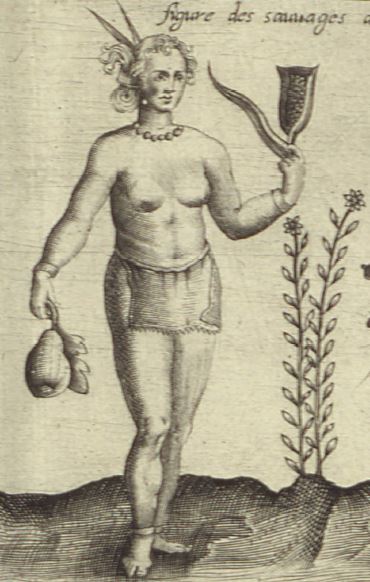

Here we see Champlain the observer in action, as his travels also involved documenting the resources of New France. For example, he purposely shows an Amerindian woman holding an ear of corn and a squash, standing beside a Jerusalem artichoke; these were three North American plants cultivated by sedentary peoples. Champlain probably took Jerusalem artichoke roots back to France, where the plant subsequently flourished.

Amerindian woman holding an ear of corn and a squash, standing beside a Jerusalem artichoke (MIKAN 3919638)

We don’t know the exact number of maps that Champlain made. Some were lost, but 22 have survived. Only one map that he drew with his own hand still exists; created in 1607, it shows the Atlantic coast, from LaHave in what is now Nova Scotia, to Nantucket Sound (the map is in the Library of Congress in Washington). Most of Champlain’s maps are small regional ones, engraved and published in Les voyages in 1613. Les voyages also has two general maps of New France: the one displayed here (1612) and a smaller one, in two versions (1612 and 1613).

One of Champlain’s regional maps, showing the Lachine Rapids (MIKAN 3919889)

Champlain started working on another general map in 1616, but he never finished it (there is only one copy of this map). The cartographer Pierre Duval, who acquired the original copper plate of the 1616 map, had another version engraved in 1653 and attributed it to Champlain. In 1632, Champlain published his last map, a synopsis map, with his Voyages de la Nouvelle-France (there are two versions of this map).

Champlain’s 1632 map (MIKAN 165287)

Champlain returned to the city of Québec for the last time in spring 1633 and died there in 1635. Perhaps we will discover another of Champlain’s maps one day. Who knows?

Tell us about another related item that you would like to add to the exhibition

Amerindians paddling their canoes (details of the 1612 map; MIKAN 3919638)

A canoe! Without the assistance of Indigenous people, their knowledge of the territory and their canoes, Champlain’s work would have been much less complete. In this map, Champlain actually depicts some Amerindians in their canoes. I would have liked to have seen one of these images in the exhibition, enlarged on a big wall behind the showcase containing Les voyages and Champlain’s 1612 map. As I already mentioned, Champlain probably initiated co-operation between explorers and Indigenous people. He questioned them repeatedly about their knowledge of geography. In some cases, he asked them to draw maps, which have unfortunately been lost.

Later cartographers also recognized the vital importance of these relationships, including Jean-Baptiste Franquelin, a very talented explorer-cartographer himself, and even later, Pierre Gaultier de La Vérendrye, who made a map by one of his guides, the Cree Ochagach, famous. Collaboration with Indigenous people continued long after the end of French rule. This watercolour, painted around 1785 by James Peachey, which was originally to be part of a map that has not been found, may very well depict the contribution of Amerindians to knowledge about the territory.

A plan of the inhabited part of the Province of Quebec, James Peachey, circa 1785 (MIKAN 2898254)

Like others before me, I’d also like to be able to show Champlain’s face. He was an intriguing man, a multi-talented leader, and was probably in excellent health; he escaped the diseases and misfortunes that claimed so many of his associates. However, there are no portraits of Champlain. The one we have all seen is a 19th-century fake. We could replace it with another imaginary portrait: the one created by the Québécois actor Maxime LeFlaguais, for example, in the recent television series Le rêve de Champlain.

Champlain’s 1612 map is a document of great historical value. It has been the subject of many research studies and, I’m sure, will continue to generate a lot of interest in the future. But it can also be looked at another way; I’d love to visit a multimedia installation, for instance, that was inspired by this map, to see how artists, particularly Indigenous artists, view Champlain, his work and his impact.

Biography

Isabelle Charron has worked at LAC since 2006, and is an archivist with the early cartography collection. She worked for many years on various exhibition projects at the Canadian Museum of Civilization (now the Canadian Museum of History). She is particularly interested in the history of cartography under French rule and during the early period of British rule. She has a master’s degree in history from the University of Ottawa.

Isabelle Charron has worked at LAC since 2006, and is an archivist with the early cartography collection. She worked for many years on various exhibition projects at the Canadian Museum of Civilization (now the Canadian Museum of History). She is particularly interested in the history of cartography under French rule and during the early period of British rule. She has a master’s degree in history from the University of Ottawa.

Related resources

Heidenreich, Conrad E., Explorations and Mapping of Samuel de Champlain, 1603–1632, Cartographica, Monograph no. 17, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1976. 140 p. (AMICUS 22100)

Heidenreich, Conrad E., Chapter 51: The Mapping of Samuel de Champlain, 1603–1635, in David Woodward, ed., The History of Cartography, Volume Three (Part 2): Cartography in the European Renaissance, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2007, pp. 1538–1549

Litalien, Raymonde, Jean-François Palomino, and Denis Vaugeois, Mapping a Continent: Historical Atlas of North America, 1492–1814, Sillery, Quebec, Les éditions du Septentrion, and Paris, Presses de l’Université Paris–Sorbonne, 2007, 299 p. Produced in collaboration with Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (AMICUS 33519157)

Litalien, Raymonde, and Denis Vaugeois, eds., Champlain: The Birth of French America, Sillery, Quebec, Les éditions du Septentrion, and Paris, Nouveau Monde éditions, 2004, 399 p. In particular, Conrad E. Heidenreich and Edward H. Dahl, “Samuel de Champlain’s Cartography, 1603–32”, pp. 312–332 (AMICUS 30651498)

Trudel, Marcel, “CHAMPLAIN, SAMUEL DE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 19, 2016 (http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/champlain_samuel_de_1E.html)

Excellent article!