Version française

By William Benoit and Alyssa White

This article contains historical language and content that may be considered offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

The federal government, in cooperation with the Roman Catholic, Anglican, United and Presbyterian churches, operated nearly 700 Federal Indian Day Schools (Day Schools) across the country, in every province and territory except for Newfoundland and Labrador. They operated from the 1860s to the 1990s. Unlike Indian Residential Schools, Day Schools were only operated during the day. However, their purpose was like that of their residential counterparts: to assimilate First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation children into white society and by extension erase their Indigenous languages and cultures.

Fishing Lake Day School, near Wadena, Saskatchewan, ca. 1948. (e011080261)

Many Indigenous students who attended Day Schools faced verbal, physical and sexual abuse during their time in that system. In addition, communities were not given a say in the curriculum or how the schools were run. It was not until the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s—when the federal government started transferring control of Day Schools to the First Nations and Inuit they ostensibly served—that these communities had any management over what and how their children were taught.

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada estimates that between 180,000 and 210,000 individuals attended a Federal Day School between 1923 and 1994, based on historical departmental enrolment data and actuarial expertise. The system did not impact all First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation in the same fashion. The largest percentage of students was First Nations, with Inuit and Métis Nation students representing smaller percentages. Each group had a unique relationship with the federal government – including whether or not the government would acknowledge the Métis or Inuit as being part of their educational or financial responsibility – and distinctive difficulties and problems were created not just in the educational services the government purported to provide to Canada’s Indigenous Peoples, but also in the care and consistency with which they kept their records.

This article will discuss the impact of the Federal Day Schools upon Métis Nation and Inuit communities, as their experiences were different and often less documented than those of First Nations.

Métis Nation children at Federal Indian Day Schools: numbers are not determinable

Did Métis Nation children attend Federal Indian Day Schools across Canada? The answer is yes, though determining the number of identifiable Métis students is practically impossible. But one can safely assume that Métis and non-Status Indian students residing in the catchment areas of Federal Indian Day Schools may have attended those schools. This is particularly probable if there was no provincial or church-run school in the vicinity for those children to attend.

The federal government has focused its attention on individuals who fall under the Indian Act. Historically, it speaks most of those who have Indian Status and less of those whom it identifies as Métis and non-Status Indian. This glib observation is key to any discussion of Métis attendance at Federal Indian Day Schools. It speaks to historical Métis access to education, health programs and other government services. Métis and non-Status individuals have been subjected to what has been referred to as a “jurisdictional wasteland” and “tug-of-war,” since both the federal and provincial governments have denied responsibility for, and legislative authority over, these peoples.

The Indian Act

One must also consider the larger discussion of status as defined by the Indian Act and how it impacts the self-identity of Indigenous peoples.

Under the Indian Act, Status Indians are wards of the Canadian federal government, a paternalistic legal relationship that illustrates the historical imperial notion that Indigenous peoples are like children, requiring control and direction to bring them into more “civilized” colonial ways of life. Federal Indian Day Schools, like Indian Residential Schools, were the federal government’s response to its need to control and direct its wards.

The Indian Act applies only to Status Indians and has not historically recognized Métis and Inuit. As a result, Métis and Inuit have not had Indian status and the rights conferred by this status, despite being Indigenous and participating in Canadian nation-building.

History and context surrounding the identification of Métis Nation children

Accurate attendance numbers of non-Status Indians (First Nations), Métis and Inuit are dependent on whether the federal government acknowledged its legal responsibility to legislate on issues related to them. For Inuit, the government’s legal obligation is usually considered to begin in 1939, following the Supreme Court decision in Reference as to whether “Indians” includes “Eskimo” (1). For Métis and non-Status Indians, the date is 2016, when the Supreme Court ruled that they should also legally be considered “Indians” under the Constitution Act (2).

Federal government records reflect the sad fact that little, or no data was collected when there was no legal obligation to serve these communities. Consequently, Federal Day School records created between the 1860s and the 1990s do not clearly identify Métis and non-Status students. A similar point could be made for Inuit prior to 1939. Unfortunately, this means that government records do not provide a clear understanding of the numbers of Métis children who attended Federal Indian Day Schools.

Inuit children at Federal Indian Day Schools: taken far from family and home

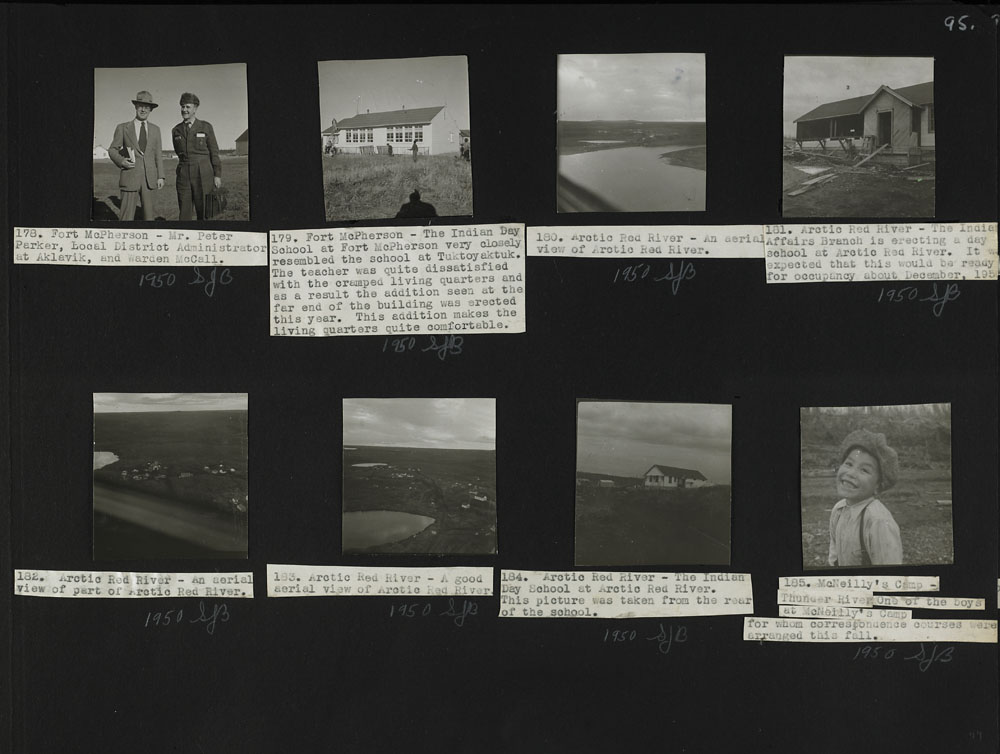

Today, four regions make up Inuit Nunangat: the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (northern Northwest Territories), Nunavut, Nunavik (northern Quebec) and Nunatsiavut (northern Labrador). While the earliest Federal Day Schools in southern Canada were opened in the early 1860s, the opening of schools in Nunavut did not occur until the late 1940s through mid 1950s.

Some of the closest school options for Inuit children would have been at Old Crow Village (Yukon), Fort Simpson (Northwest Territories), Churchill (Manitoba), Fort Severn (Ontario) and Fort George (Quebec), but these schools were not necessarily permanent. It was not uncommon for remote Day Schools to close periodically for years.

In contrast to Indian Residential Schools (or Federal Hostels), which housed students on site and away from their families and homes, Day Schools were built so that students would be able to return home after their school day and not be required to travel extended distances to live elsewhere for months at a time. The catch to this was that Day Schools were typically only built on or near First Nation communities, with little consideration of Inuit communities and students until the 1940s.

Although Day Schools were intended to prevent separation and alienation, Inuit children would end up being taken, sometimes suddenly and without warning for extended distances to live elsewhere to attend a Day School. The schools were often located in areas with completely different climates, ecosystems, social cultures and languages, with unrecognizable plants or animals. Shock would be too gentle a word to describe the sense of alienation those children must have felt on arrival.

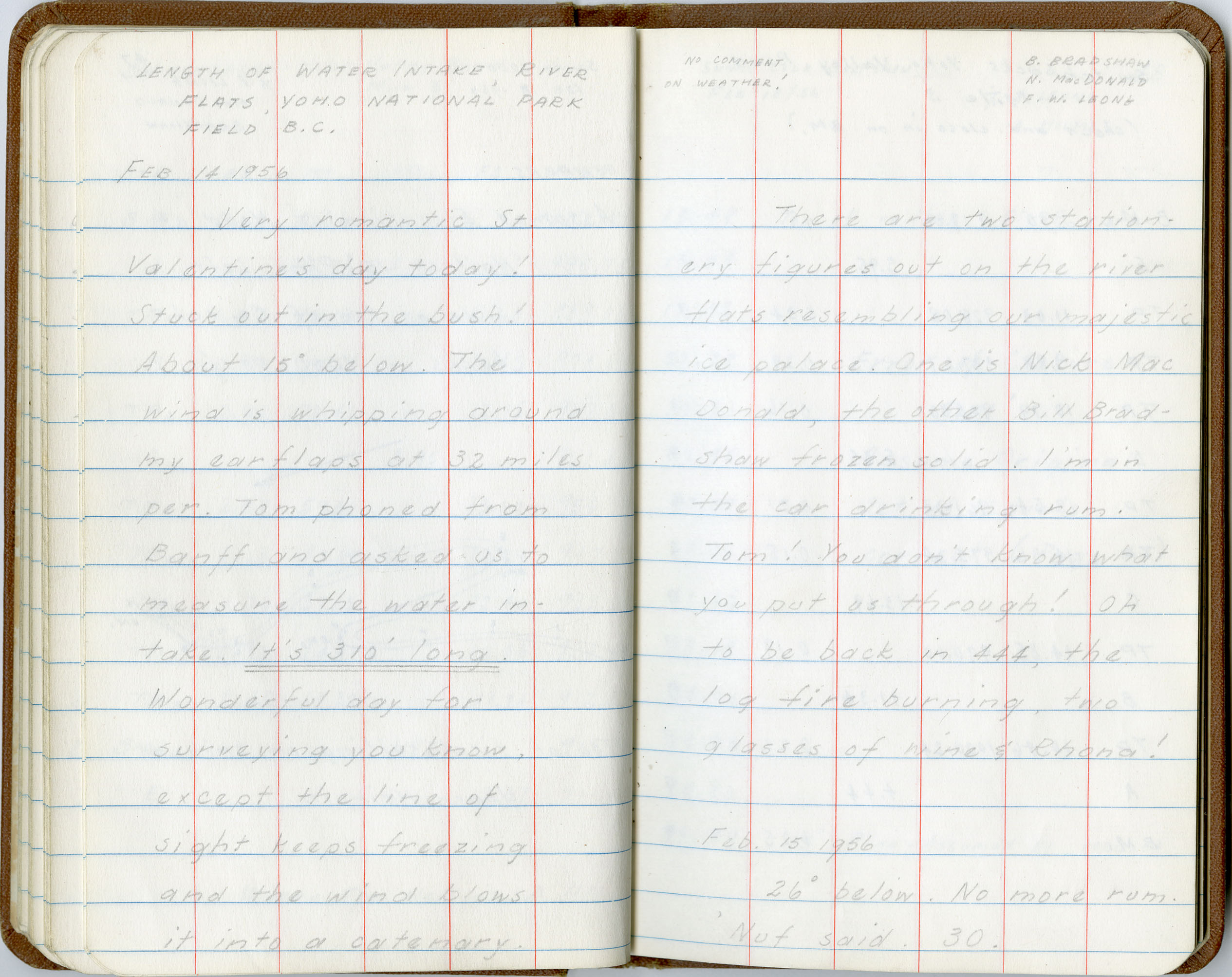

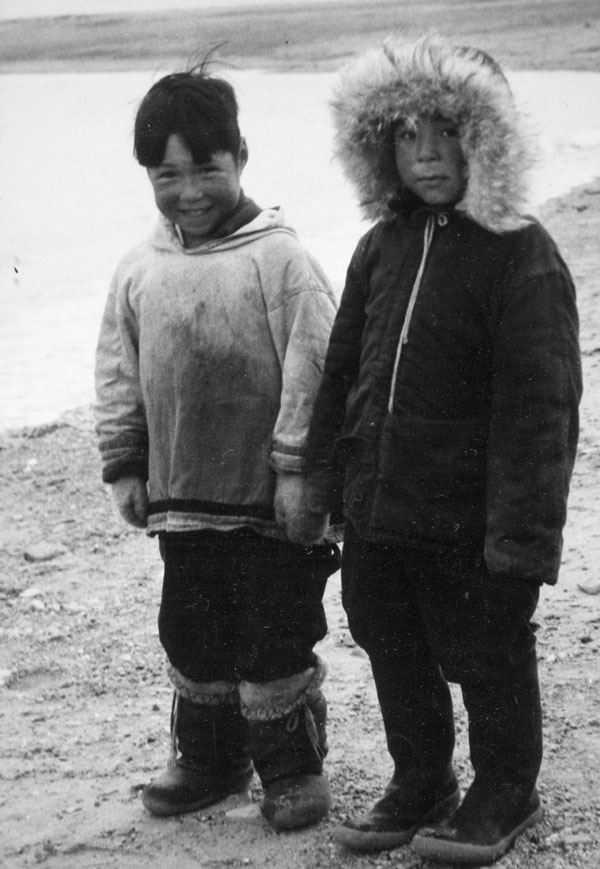

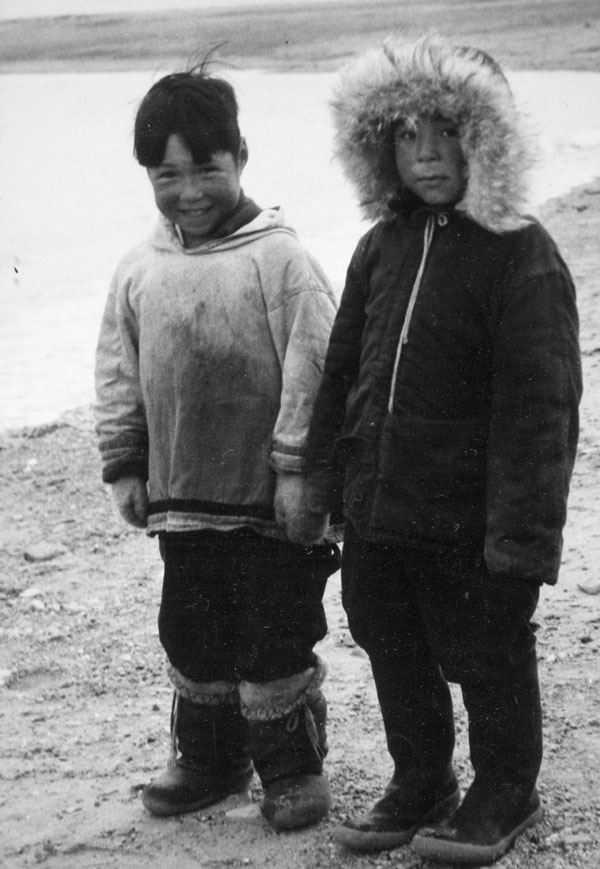

This picture below, by all appearances, shows a happy moment caught on film: two smiling boys enjoying a day out with their families to see an airplane in the hamlet of Iglulik. What this photograph does not show is what happened minutes later, when the boys were put onto the plane and taken 800 kilometres away to Sir Joseph Bernier Federal Day School in Igluligaarjuk (Chesterfield Inlet) without any prior knowledge of what was about to happen. (3)

Kutik (Richard Immaroitok) and Louis Tapadjuk (right), Iglulik, Nunavut, 1958. (e004923422)

Considering that school attendance was compulsory by the 1920s, one can imagine the compounded stress and fear experienced by Inuit families when it came to federal control of their children’s education.

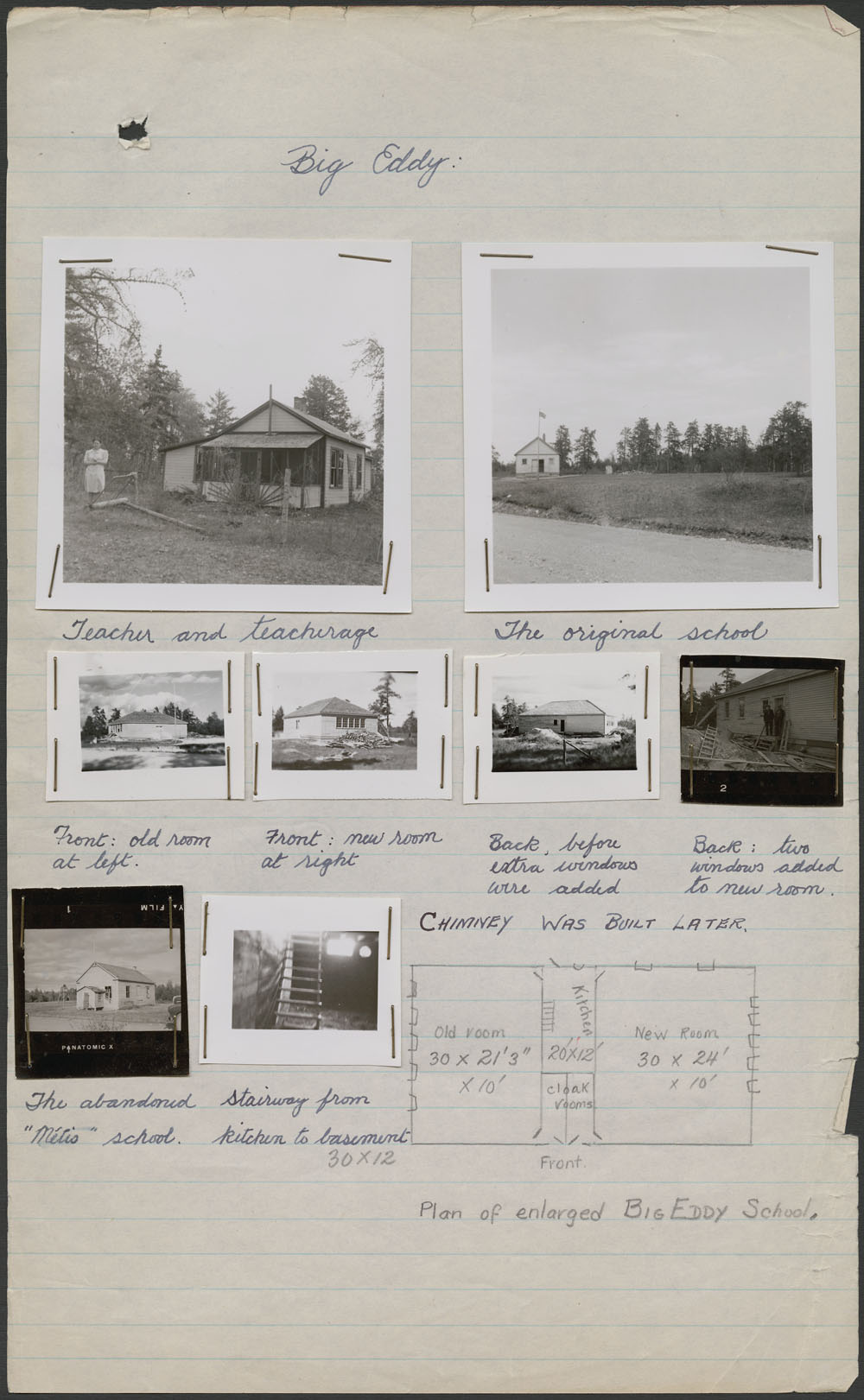

Day Schools in the North were not large facilities, commonly consisting of one to three classrooms and a teacherage, facilitating anywhere from eight to two dozen students at a time depending on location and local population. Once a school was full, any additional children in the area would have been sent further south and west until room could be found for them.

Reindeer Station Day School, Qunngilaaq, Northwest Territories, between 1950 and 1960. (e011864959)

Children who did not have access to a local Day School were sent to residential, boarding or foster homes in communities ranging anywhere from hundreds to thousands of kilometres away from their families and everything that was familiar to them. They would be handed over to the care and keeping of total strangers, in places that would have been entirely strange to them, that they were not free to leave. Visits from family were not guaranteed due to travel costs and time. This meant that Inuit students were separated from their families not just for months but occasionally for years at a time.

Between the 1940s and 1980s, more schools were built across the country, including locations in the far North, such as those serving the remote communities on the southern shore of Ellesmere Island and Resolute Bay in Nunavut.

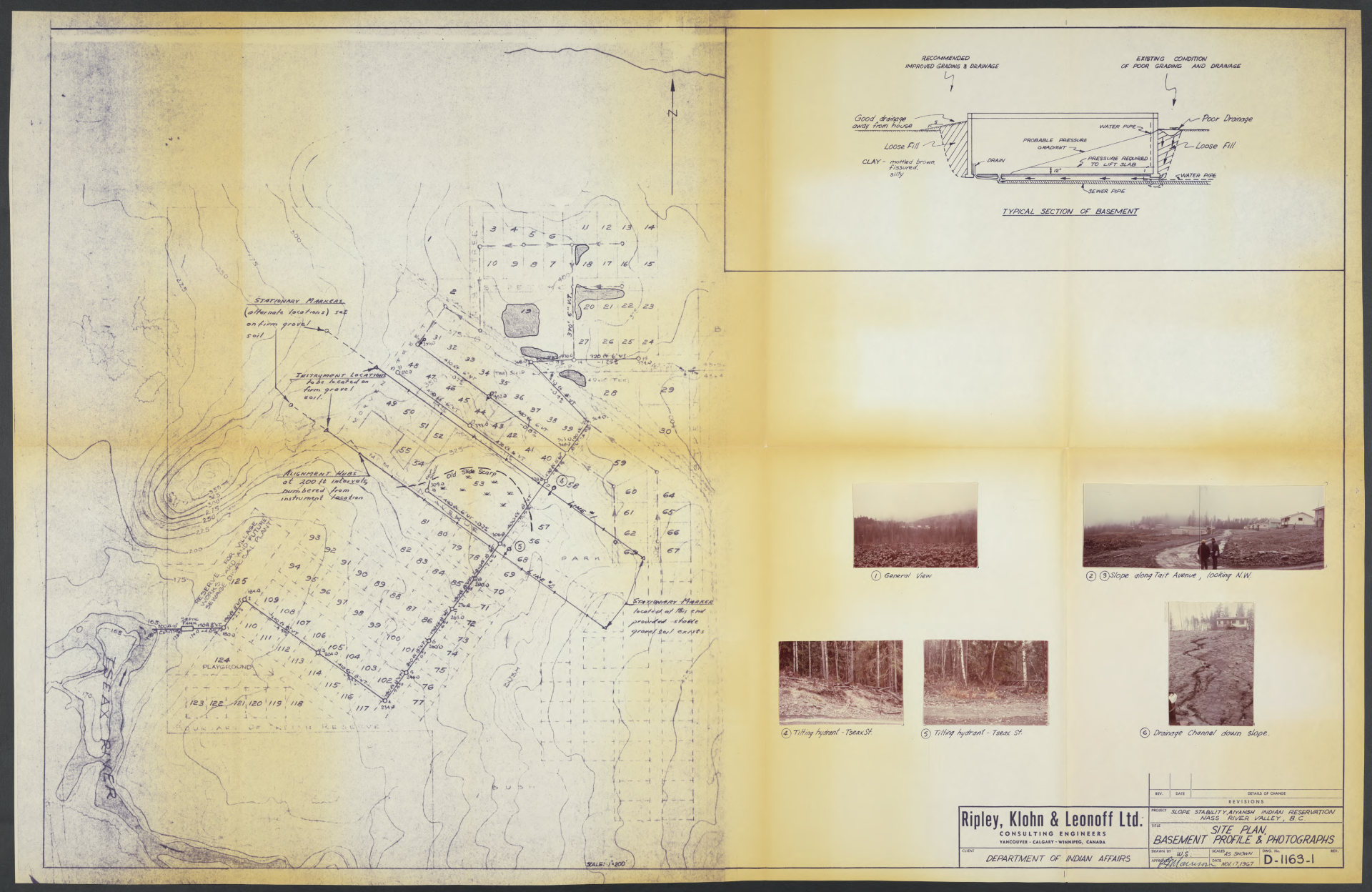

To give a better idea of the spread and demographics of Day Schools in Canada and the struggles of remote communities, of the 699 Day Schools on record, a total of 75 were opened across the combined land masses of the Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut and northern Quebec. Only seven of those existed prior to the 1940s (in the Yukon and Northwest Territories), with the other 68 being built between 1940 and 1969.

The Day Schools Project

The Day Schools Project (DSP) is identifying, describing, digitizing and making accessible government records that include information pertaining to Federal Indian Day Schools. The project’s goal is to prepare these files and documents for public access.

The records being digitized include nominal rolls from various schools across Canada as well as information regarding foster homes, boarding homes, hostels, transfer requests and authorizations, adoption records and school discharge records. These can be used to trace the trail of schools and homes that many Indigenous children passed through.

It is important to note that most of the Day Schools records are restricted by law but can still be accessed according to access to information and privacy legislation. The DSP is trying to build foundations to make access to records as easy as possible. This includes identifying ways to make current procedures and resources easier for people to understand and navigate, for example, by adding detailed information to the archival records. To learn more about accessing records digitized by the DSP, see the Day Schools Project: Overview and the Day Schools Project: Research Guide.

Besides making information more accessible to Indigenous communities, Day School records can be accessed by the public, many of whom were never taught about these histories and as a result never truly understood the scope of the scars they have left behind.

Ultimately, First Nations, Inuit and the Métis Nation need access to the histories for healing, finding closure and continuing the work of building towards their futures. The general Canadian public needs access to these histories to better understand the realities of how this country was formed and to support a future that is and does better for all its people.

The road to reconciliation is long, but the key to progress is in access to information and public education. Indigenous data sovereignty and community access to documents remain some of the greatest hurdles still to overcome.

Additional resources (Library and Archives Canada)

- Day Schools Project: Overview

- Day Schools Project: Research Guide

- Understanding Day School Records at Library and Archives Canada

- Blog article about the Day Schools Project

- Indian Residential School records: Overview

- Indian Residential School records: Research guide

- School Files Series—1879–1953 (RG10)—Library and Archives Canada

- Provides links to digitized Residential and Day School files on microfilm

- We Are Here: Sharing Stories

- Mass digitization initiative (2018–2021, 2022–2024) that provides access to textual material, photographs, artwork, maps and publications related to First Nations, Inuit and the Métis Nation found in government and private records and published works

- Roy and Marg Hall fonds

- Photographs of the Day School, Vuntut Gwitchin community, in Old Crow, Yukon, 1961 to 1964

- Bernice Logan fonds

- Photographs depicting the staff and students at Indian Residential Schools across Canada from 1926 to 1991, with the majority taken in the 1940s and 1950s

- Joseph Vincent Jacobson and family fonds

- 1,370 photographic records related to Federal Indian Residential Schools and Day Schools in Nunavut, Northwest Territories, Alaska and Greenland, dated ca. 1950–1973

- Census search

- Unmarked burials

- Sources and strategies to help identify burial sites associated with Indian Residential Schools. It can also help identify names of children who went to these schools and hospitals

External resources

References

- Reference as to whether “Indians” includes “Eskimo,”1939 CanLII 22, [1939] SCR 104 is a decision by the Supreme Court of Canada regarding the constitutional status of Inuit in Canada. The case concerned section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867, then the British North America Act, 1867, which assigns jurisdiction over “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians” to the federal government. The Supreme Court found that for the purposes of section 91(24), Inuit should be considered Indians.

- Daniels v. Canada (Indian Affairs and Northern Development), 2016 SCC 12, [2016] 1 SCR 99 is a decision by the Supreme Court of Canada regarding the constitutional status of Métis and non-Status Indians in Canada. The Métis Nation and non-Status Indians are also “Indians” under s. 91(24). The Supreme Court of Canada ruled in Daniels v. Canada that the federal government, rather than provincial governments, holds the legal responsibility to legislate on issues related to Métis and non-Status Indians. Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867 concerns the federal government’s exclusive legislative powers.

Note: Recognition as Indians (First Nation individuals) under this section of law is not the same as Indian status, which is defined by the Indian Act. Therefore, the Daniels decision does not grant Indian status to Métis or non-Status peoples. However, the ruling could result in new discussions, negotiations and possible litigation with the federal government over land claims and access to education, health programs and other government services.

- Greenhorn, Beth. “The Story behind Project Naming at Library and Archives Canada.” In Atiquput: Inuit Oral History and Project Naming, edited by Carol Payne, Beth Greenhorn, Deborah Kigjugalik Webster and Christina Williamson, 70-71. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022.

William Benoit is the Indigenous Advisor on the Day Schools Project.

Alyssa White is an Archival Assistant on the Day Schools Project.