By Stephen Danilovich

Imagine that an archive of you has been donated to Library and Archives Canada (LAC). Picture the sorts of things that make it into your collection: a high school diary, this month’s grocery receipts, your last social media post.

Now imagine that you are the archivist processing your own archive. How would you organize all of these items into distinct groupings? Where would you restrict access to sensitive information, and why? And would you try to describe your records fairly … or would you be tempted to tidy things up?

These are some of the questions that arise when working with personal archives: archives produced by individual people, as opposed to institutions or corporations. Needless to say, things can get personal with personal archives. Nowhere else do questions of privacy, original order, donor relations and other archival concerns come into contact so closely with the day-to-day questions of being human.

One thing that makes personal collections unique is that they tend to turn the tables on you, the archivist. You start to consider all of the traces you leave behind, how some future archivist might try to piece together your life. You also notice the many things that slip through the cracks and go unrecorded.

As any archivist will tell you, much of an archivist’s work happens in those blind spots. An archivist has to draw connections between or across the actual items, creating an intellectual arrangement that will give future researchers a way into the collection. So what happens when archivists try to create intellectual order out of a human life, its records and traces?

Two ways of seeing: negative, positive. Miss Ethel Hand, November 10, 1934, photo by Yousuf Karsh (e010680101)

To answer this question, I spoke to archivists in the Social Life and Culture Private Archives Division, which includes the collections of such celebrated authors as Carol Shields, Michael Ondaatje, Daphne Marlatt and others. The fact that many of these authors are still living today makes these questions all the more vital.

“It puts your own life into perspective,” says archivist Christine Waltham, who has been working with the collection of Thomas King. “It’s someone giving their life, really.”

“You really feel you know these people,” says Christine Barrass, a senior archivist whose first encounter with personal archives was the fonds of Doris Anderson. “It seems very transactional, but when you get to know the nitty-gritty of it, it’s a real honour and a real privilege.”

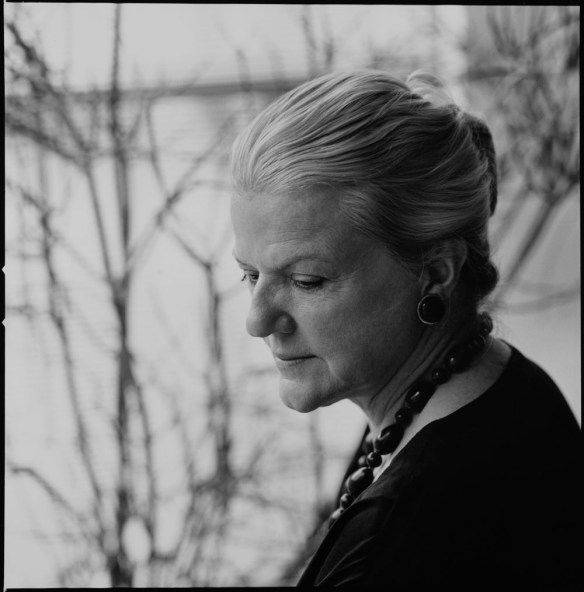

A portrait of a subject: Doris Anderson, October 10, 1989, photo by Barbara Woodley (e010973512)

Perhaps the most unexpected challenge to arise while working with personal archives is the emotional investment that the archivist can begin to develop for the archive and its creator.

“The emotions that come up, that you don’t get in institutional archives, that can be hard to deal with,” Waltham says. “How to describe it respectfully.”

“It can be a bit too much, if that’s not something you want in your daily life,” explains Barrass, who believes that the good and the bad about personal archives are two sides of the same coin: how intimate things can get.

Often, the archivist is the first person to see the material aside from the creator, which calls for an implicit relationship of trust. This privileged view of someone’s life comes with a deep sense of responsibility, leading to what Catherine Hobbs, a literary archivist, calls “archival paranoia.”

“It is the sense of never being able to do enough,” Hobbs says, “which is the sign of any responsible archivist.”

Processing someone’s archive becomes a constant tightrope walk between the creator’s public and private lives. Any item can turn out to be a clue to a secret affair, a feud kept under wraps, or a side of the person that no one knew before. To add to the stakes, what future researchers will find useful can be impossible to predict.

All this requires a careful balancing act between the donor’s privacy on the one hand and access for future researchers on the other, while at the same time upholding LAC’s mandate.

“Our role is to stand in the middle distance: act as guardian, and as the facilitator of research,” says Hobbs.

It is this strange mix of personal intimacy and a bird’s-eye distance that makes working in personal archives so special.

Between mirror and lens: “The Mob,” Dominion Drama Festival, April 24, 1934, photo by Yousuf Karsh (e010679016)

As a summer student employee, taking on archival work for the first time, I hoped to get some clarity on the proper practices for processing a personal archive. But I quickly learned that personal archives are as varied and nuanced as their creators.

“The messiness of life that’s in personal archives is what makes it special,” Waltham says.

And that messiness requires a special touch. Given how unique each personal collection is in both arrangement and content, being too prescriptive about predetermined procedures for creating intellectual order may not always be the best approach. If an archivist tries to formalize too much, some of the uniqueness of a collection could be lost.

“How much you can tell just from what the records look like, the conditions they were kept in,” Waltham adds, “that says a lot about the person.” An overly standardized processing method could mean losing some of that granularity. One could even claim that personal archives go beyond the realm of social science and into something like art—even a collaboration with the archive’s creator.

Hobbs argues that working in an archive is more than a science, “it’s a responsible practice.” The most important thing that an archivist can bring to a personal archive is a sense of “the honesty of the endeavour”: being present with the actual life of these records in an empathetic way, and understanding the rare intimacy that is involved when someone gives up such a private part of himself or herself.

After all, maybe what is required for personal archives is a little self-awareness on the part of archivists—an understanding of the role they play in this grand procession between everyday human lives, record keeping and research. Creating order out of someone’s personal records is itself an unavoidably personal practice. Archivists working with personal archives have to be especially sensitive to the way that we are all participating in what Hobbs calls this “human experiment,” co-creating as much as we are cataloguing when we try to make sense out of another human being.

For all the challenges and emotions that come with personal archives, archivists at LAC do the best they can. The ultimate hope, as Hobbs puts it, is to “leave the archives better than we found them.”

Stephen Danilovich is a student archivist in the Social Life and Culture Private Archives Division of the Archives Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

So who was Miss Ethel Hand of 1934, I wonder. Do you have further information on her? Thank you for the blog by the way. karenprytula33@gmail.com