By Dylan Roy

Sometimes you come across a record that doesn’t necessarily make sense at first glance. This was my experience when I first looked at the archival description of the series HMCS Griffon. HMCS stands for “His/Her Majesty’s Canadian Ship” (you can find this and other military abbreviations used in service files on Library and Archives Canada’s website—this page is a wonderful tool for those not familiar with military abbreviations). Therefore, it shouldn’t be a surprise that I assumed these files were about a ship.

But lo and behold, me mateys, upon consulting the files I discovered that the “ship” turned out to be a facility in Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay).

Photo of HMCS Griffon. Source: Government of Canada, National Security and Defence, Ships’ Histories: HMCS Griffon. Credit: Courtesy of The Royal Canadian Navy.

As the series relates, “[a] vacant garage was leased by naval reservists at the beginning of the Second World War, and, with the establishment of a policy of commissioning all ‘stone frigates,’ the garage became HMCS Griffon in 1941.” This led me down a rabbit hole of secondary sources to learn about stone frigates.

A stone frigate, to put it simply, is a naval vessel established on land. The British first employed this informal term: to bypass legal obligations that prevented them from ruling “over land,” they decided to commission the island Diamond Rock as a ship during one of their many wars with the French. This is a good way of understanding HMCS Griffon and its seemingly confusing title.

The official badge of HMCS Griffon. Source: Government of Canada, National Security and Defence, List of Extant Commissioned Ships: HMCS Griffon. Credit: Courtesy of Department of National Defence.

From the Ships’ Histories on the Canadian government’s National Security and Defence web page, I learned that HMCS Griffon’s creation was based on several factors, most notably its relationship with the Sea Cadet program and the influence of the shipping industry in the Great Lakes region. HMCS Griffon was commissioned in 1940 and moved to its current location in Thunder Bay in 1944. During the Second World War, HMCS Griffon guided newly recruited sailors eastward as they made their way out of the prairies, thus indicating the importance of the facility’s geographic location in Canada.

Once I read up on these facts, I could better contextualize the records we have in our archival collection at Library and Archives Canada—this just goes to show how secondary source work can help researchers gain a better understanding of archival records (primary sources).

As mentioned, the first record I stumbled upon concerning HMCS Griffon was its series-level archival description. Reading through the series, I learned that it only contained five file-level descriptions as well as a linked accession.

Save for the accession, all the files were open, so I decided to peruse their contents. As luck would have it, all the files are found in the same archival box, Volume 11469 (an archival box is equivalent to an archival volume).

With the volume ordered, I was able to delve into the archival treasures found therein, which I shall share below.

The first file, HMCS GRIFFON: Ceremonies and functions, Official opening of HMCS GRIFFON, is a good file to start with as it shares some interesting discussions on the opening of the facility in 1944 and on its namesake. HMCS Griffon was named after a ship dubbed Le Griffon, which was constructed by storied French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle.

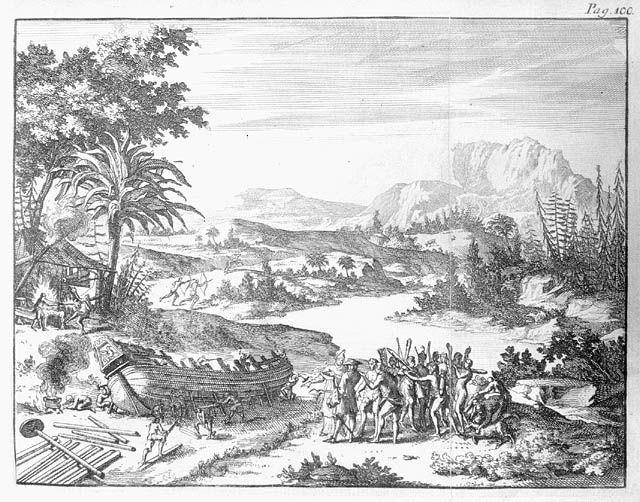

The building of La Salle’s Le Griffon (c001225).

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (c007802).

Le Griffon set sail in 1679 to take part in the burgeoning fur trade. Notably, it was the first full-sized sailing ship on the upper Great Lakes—this is the source of HMCS Griffon’s motto PRIMA IN LACUBUS (First on the Lakes). On its maiden voyage, Le Griffon set sail from an island near Green Bay, Wisconsin, and the ship was never seen again. This mystery intrigued many, including the commanding officer of HMCS Griffon, H.S.C. Wilson.

Wilson had received a bolt from a wreck, supposedly Le Griffon, that had been discovered in 1931 in the Mississagi Strait, near Manitoulin Island. Contrarily, a story surfaced about an Indigenous oral story of the real wreck of Le Griffon being close to Birch Island, near “Lescheneaux” or “Les Cheneaux.” C.H.J. Snider, of the Toronto Evening Telegram, returned a telegram to Wilson refuting the assertions of the latter wreck. This exchange shows the interest that some HMCS Griffon servicemen and women had in the history of their namesake. The location of the wreckage of Le Griffon remains a mystery to this day.

This exchange of telegrams was just part of the file. There were other notable entries, such as the invitation lists for the inauguration of HMCS Griffon and the various preparations made for the event.

Another fascinating file found in the series is HMCS GRIFFON: Reports of proceedings. Reports of proceedings are truly remarkable files as they demonstrate the day-to-day activities within a military establishment via various departments. For example, I was able to determine from the Sports Department that the popular sports at HMCS Griffon included basketball, volleyball and badminton. From a report in May 1955, I learned that baseball was less popular, as “[a]ttempts have been made to organize baseball games but insufficient interest was shown.”

Moreover, we can see the impact that marriage had on some servicewomen in a quote from a report posted by the Medical Department dated February 1955: “Wren Kingsley of the Medical Branch has been discharged following her recent marriage … Lt. Reta Pretrone was married this month resulting in absenteeism from several drills.”

These reports can shed light on both the operational management of the naval establishment as well as the more mundane happenings of HMCS Griffon.

As HMCS Griffon saw many men and women serve at the facility, accidents were bound to happen. The next excerpt, from the file HMCS GRIFFON: General information, RN personnel, shows us, in gruesome detail, a Board of Inquiry in 1945 about an unfortunate accident that occurred in the installation:

Board: What were you doing, that is, just what happened?

Answer: Machinist work, wood-cutting grooving some pieces of wood for boxes. It was a two inch mechanical saw and wood was brought across the bench and off about three feet from the side with about one foot space between the end of the wood and the wall. Most of the wood was wet, this piece was quite wet on the grain and dry on the end. As I was sawing this piece a young boy was trying to get around behind me, I turned my head to see that he did not shove me when at that moment the saw hit the dry end of the wood and it went through the wood very quickly taking my hand with it and cutting my fingers.

Following the inquiry, the board concluded:

It is the opinion of the board that Stoker BLACKMORE E suffered this accident while on leave and that it was not due to Naval Service. The Canadian Naval Authorities permit ratings to work whilst on leave thus alleviating the shortage of manpower. It is felt that this rating was justified in taking up this employment as it is his vocation in civilian life and the accident was primarily due not to inexperience on his part but to the fact that no guard or safety arrangements were supplied for this machine.

The Board of Inquiry process provides a glimpse into some of the practices that the Naval Service employed, such as employing a rating (a junior enlisted serviceman) instead of active servicemen when faced with shortages of manpower. It also illustrates some of the safety precautions, or lack thereof, on HMCS Griffon.

The files of HMCS Griffon series yielded some interesting facts about the stone frigate. Moreover, it gave me some broad and vivid descriptions of multiple events that transpired over time at the installation. It also shows how we can meld secondary sources with the primary sources themselves. All that said, HMCS Griffon will be remembered, in my mind, as the First on the Lakes.

Dylan Roy is a Reference Archivist in the Access and Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

Dylan, Fascinating story and one I had never heard, even with so many trips to Port Arthur from my hometown of Terrace Bay. Thanks!

Fred

Hi Fred! Thank you very much for your comment. I am pleased that I was able to shed some light on an aspect of the history of your region. It was a very interesting endeavor for me and it gives me great joy knowing that others, especially those from around the area, find the story of HMCS Griffon interesting! Thanks again.

-Dylan

When my father grew up in Owen Sound in the 1930s and 40s, there was an old guy around, Orrie Vail, who claimed he had found the wreck of LaSalle’s ship off Tobermory. One of many such claims, I suppose?

That is very intriguing indeed! It seems there were many who have claimed to have found the wreck and that’s what I find so fascinating about this ship. Because the ship was mainly made of wood and therefore deteriorates quicker over time, it’s hard to validate the claims. Nonetheless, it does not mean that the ship wasn’t actually found but rather, there does not seem to be a consensus over its discovery at this time. Thank you so much with engaging with my content! – Dylan