By Rebecca Murray

Please note that many of the visuals for this article were taken from digitized microfiche; as such, the image quality varies, and individual item-level catalogue descriptions are not always available.

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) is celebrating 100 years in 2024. Library and Archives Canada (LAC) holds records from the RCAF’s earliest days through to the 21st century. From its role in Canadian aviation to operations abroad, the RCAF has an important place in Canadian military history. Other posts on this site address infrastructure like airports (specifically RCAF Fort St. John) and notable moments such as the Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow. This post will focus on the photographic holdings of the RCAF at LAC, specifically the Second World War–era photographs of servicewomen.

HC 11684-A-2 “Great coat with hat and gloves,” 04/07/1941 (MIKAN 4532368).

Another colleague’s post outlines the history of the RCAF Women’s Division (RCAF-WD), so I won’t repeat it here, except to say that it was formed on July 2, 1941 (officially as the Canadian Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, changing its name by early 1942) and would eventually see more than 17,000 women serving within its ranks.

PBG-3143 “Women’s Division—Aero Engine Mech.,” 23/10/1942 (MIKAN 5271611).

The Department of National Defence fonds (RG24/R112) holds photographs of these women and documents their service during the Second World War era. Comprising over 500,000 photographs, this collection is a rich resource for anyone interested in the period as it includes photographs from both Canada and overseas. Over the past six years, I have been working closely with the photographs to find the servicewomen. Some of them are documented clearly and given centre stage in photographs. Others are found on the fringes, sometimes almost indistinguishable at first glance from their male counterparts in group photographs.

RE-1941-1 “Pay and Accounts Section (Crosswinds),” 25/09/1944 (MIKAN 4740938).

The occasion of the RCAF’s 100th birthday is a fitting moment to share the results of the work with this particular sub-series of photographs while highlighting the role that servicewomen played in the RCAF’s ranks during this period. Composed of 53 sub-sub-series of photographs, usually distinguished by location, the images vary widely—from aerial views of Canada to official portraits to post-war photographs of life and operations at European bases like North Luffenham and Station Grostenquin. The bread and butter of this sub-series, though, for most interested parties, is the imagery that documents the day-to-day operations and lives of servicemen and women during the Second World War, whether at home or abroad.

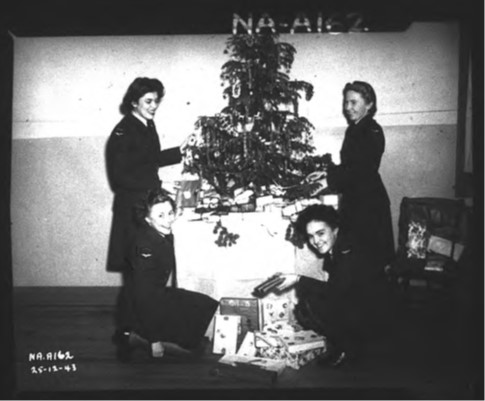

NA-A162 “WD’s Xmas tree & Xmas dance,” 25/12/1943 (MIKAN 4532479).

At over 160,000 distinct images, this sub-series is a treasure trove for any researcher with an interest in the period! Approximately 1,900 of those images (1%) are of servicewomen, both RCAF-WDs and nursing sisters who served in the RCAF. Servicewomen are best represented within this sub-series in photos from Ottawa, Rockcliffe or Headquarters, with strong representation from those taken at regional bases such as those in Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island and British Columbia.

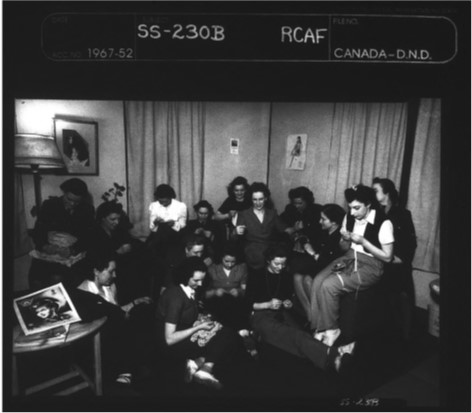

The photographic collection shows us the WDs (as they were known colloquially) at work and play. They are often shown in groups celebrating holidays or fun moments against the backdrop of a horrific war. Other images suggest levity (see images NA-A162 above and SS-230B below) but also show the serious work being done (see image PBG-3143 earlier in this post). Formal group photographs, such as the nursing sisters shown in G-1448 below, are very common. For many of the more remote or rural bases, especially in the earliest years of the war, nursing sisters are the only women present in the associated photographic records.

G-1448 “[Hospital staff, No. 1 Naval Air Gunnery School, R.N., Yarmouth, N.S.],” 05/01/1945 (a052262).

SS-230B “Sewing Circle (WD’s) Intelligence Officers,” 04/04/1943 (MIKAN 5285070).

Do you want to know more? Did your aunty or grandma serve in the RCAF-WD? Are you interested in knowing more about her service?

Check out LAC’s extensive resources and records related to the Second World War, including information on how to request military service files. Service files for Second World War—War Dead (1939–1947) are available via our online database.

Explore other photographic holdings at LAC, such as the PL prefix—Public Liaison Office sub-sub-series, a fabulous resource for RCAF photographs that sits, archive-wise, just outside of accession 1967-052 (the focus for this particular research project). Any researcher looking for a RCAF aunty or grandma (or grandpa!) in the archives should include these photographs in their search.

There’s more information about the RCAF’s Centennial on the official RCAF website.

Rebecca Murray is a Literary Programs Advisor in the Programs Division at Library and Archives Canada.