Treaties between Indigenous peoples and settlers were made during early contact and continue to be negotiated today. Subsection 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982 recognizes and affirms the existing Aboriginal (Indigenous) and Treaty rights of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Library and Archives Canada’s (LAC) holdings include pre-Confederation and post-Confederation Indigenous treaties and treaty-related material. A range of this content is available on our website, to promote public awareness and improve access. Modern treaty agreements are located in the Inuit and Indian Affairs Program sous-fonds. LAC preserves many treaties but does not have all of them. There are descriptions of modern treaties in our catalogue, but some are not yet available for public viewing. Many early treaties and agreements from the Western and Maritime regions are archived in other institutions.

Treaty with Saskatchewan Saka wiyiniwak (Cree) at Fort Carlton (Western Treaty No. 6) (e002140161)

The word “treaty” may seem like a dated diplomatic term. In fact, treaties are constitutionally recognized agreements between the Crown and Indigenous peoples. They are therefore still negotiated and signed today. Treaties document how Canada developed into its present form. The historical development of treaties is very complex, and each is unique. Ideally, the intent and scope of a treaty should be based on a clear, shared understanding of the interests and outcomes for the participating parties. In reality, the early treaties were agreements between two parties from two different cultures, which affected understandings and outcomes. Many of these types of documents were detrimental for Indigenous people, resulting in the erosion of their culture and the loss of their territorial land bases.

Western Treaty No. 5 – treaty and supplementary treaties with First Nations at Berens River, Norway House, Grand Rapids and Wapang – IT 285 (e002995143)

First Nations treaty monument at Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan (Western Treaty No. 4) (a019282)

Pre-Confederation: from contact to 1867

Treaties before Confederation involved several changing political entities. The colonists involved may have been Dutch, French, British or other; the land may have been classified under names like New France, British North America, Rupert’s Land, Upper Canada, Lower Canada, Canada West (Ontario), Canada East (Quebec) and Colonial America (the Thirteen Colonies). Early Eastern treaties were known as “peace and friendship” treaties, since their purpose was to prevent conflict. Some involved protocols with the use of oral traditions, symbolic items and gestures such as using pipes, tobacco and wampum belts. This conveyed and signified the importance of a shared message. Beginning in 1818, annual treaty payments were made to individual First Nations who had signed treaties. This practice continues with some disbursements still honoured today and paid out to those who are eligible.

Post-Confederation: from 1867 to 1975

The Western numbered treaties, from 1 to 11, covered areas from the southern tip of James Bay and west to the Rocky Mountains, from the United States boundary line and north to the Beaufort Sea. These should not be confused with the Upper Canada Land Surrenders, which are also numbered. Most of the western plains were ceded to the Canadian government through treaties, which was significant because the Royal Proclamation of 1763 stated that settlers could not occupy land unless it had been surrendered to the Crown by First Nations. In 1871, British Columbia was brought into Confederation with the promise of a transcontinental railway within 10 years. Manitoba was created out of Rupert’s Land in 1870, with Alberta and Saskatchewan following in 1905.

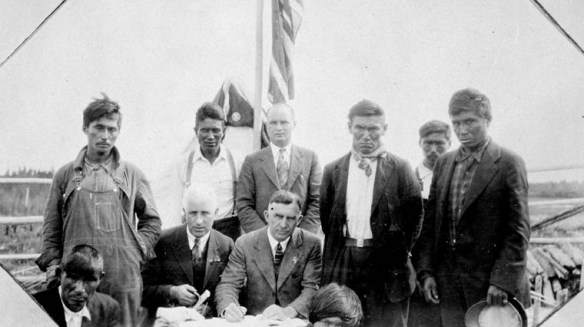

Signing of the treaty at Windigo, Ontario, on July 18, 1930 (Western Treaty No. 9) (C068920)

1937: “6 A.M. and the treaty dance is still going strong” at Fort Rae, Northwest Territories; Tlicho (Dogrib-Behchoko/Rae-Edzo/Edzo) (a073741)

Maskeko wiyiniwak (Cree) camped along the shore in 1935 for Treaty 9 payments at Moose Factory, Ontario (a094977)

Modern treaties: from 1975 to the present

The landmark James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (1975) was the first major agreement between the Crown and Indigenous peoples in Canada since the numbered treaties. It was amended in 1978, by the Naskapi First Nations, who joined the accord through the Northeastern Quebec Agreement. Additional agreements followed: the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (1993), the Nisga’a Final Agreement (2000), the Labrador Inuit – Nunatsiavut (2005) and the Nunavik Inuit – Northern Quebec (2006) agreements, the Eeyou Marine Region Land Claims Agreement (2010), the Tshash Petapen (New Dawn) Agreement with the Innu of Labrador (2011), and more.

Treaties Recognition Week Act, 2016 (Ontario)

Williams Treaty No. 2 – Mississauga First Nations of Rice, Mud and Scugog Lakes and Alderville – IT 488 (e011185581)

The Treaties Recognition Week Act, 2016 was recently enacted by the Government of Ontario. During Treaties Recognition Week in 2018, LAC displayed the original Williams Treaty of 1923, the last historic land cession treaty in Canada, at the University of Ottawa.

The Lubicon (Saka wiyiniwak) Land Claim Settlement (2018)

A land claim settlement was awarded to the Lubicon Lake Band of Cree in Northern Alberta in 2018. They were inadvertently not included in Treaty 8 in 1899, and for decades they had asked the federal and provincial governments to allocate a reserve for them. By the 1980s, oil exploration and wells in their traditional territory made their claim urgent. They made themselves heard in 1988, when the Winter Olympics were about to be held in Calgary, Alberta, with a boycott of a landmark exhibition of Indigenous art and culture, “The Spirit Sings” (ironically, it was originally titled “Forget Not My Land”).

Elizabeth Kawenaa Montour is a project archivist in the Exhibitions and Online Content Division of the Public Service Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/blog-banner.jpg?w=584)

So does signing of treaties mean indigenous peoples have the first right to land? For how long does a treaty last? What if indigenous people refuse to sign a treaty? Can they cancel a treaty?

If you would like more information or sources about treaties, our Reference service can point you in the right direction. Here is a link to the online form: https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/assistance-request-form/Pages/assistance-request-form.aspx?requesttype=3. You may also be interested in this blog post: https://thediscoverblog.com/2019/06/21/treaties-with-indigenous-peoples-past-and-present/.