By Sevda Sparks

A potlatch is a ceremonial gift-giving feast practiced by indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest in Canada and the United States. The Canadian government’s potlach ban began in 1885, and underwent many amendments to strengthen it until its removal in 1951. Library and Archives Canada’s holdings include a wealth of material on the potlatch, including many letters and petitions on the suppression of the custom as well as efforts to continue it. Of special interest is the correspondence of Kwakwakawakw Chief Billy Assu, Indian Agent William Halliday, and British Columbia Chief Justice Matthew Begbie.

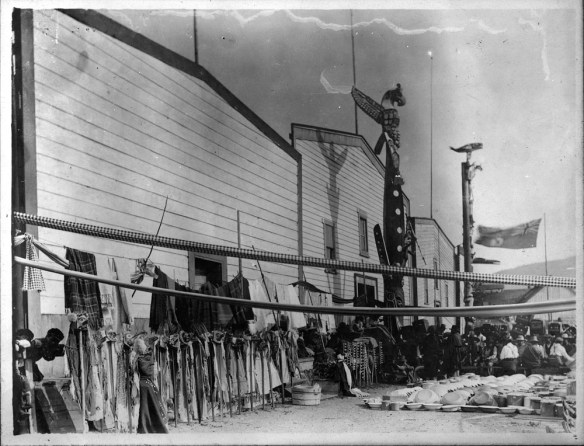

Potlatch, Alert Bay, British Columbia, June 1907 (MIKAN 3368269)

In the midst of the potlatch ban, Chief Billy Assu wrote to the deputy superintendent of Indian Affairs, J. D. MacLean, in 1919, explaining the potlach or “our old custom of giving away.” In describing the roots of the celebration, and the desire to retain it, Assu stated:

“We all know that things are changing. In the old days, the only things that counted were such things as food, dried fish, roots, berries, and things of that nature. A chief in those days would get possession of all these things and would pass them on to those who had not got any… ”

The potlach was a way to hold onto important cultural customs despite the changing times. Assu also commented more broadly on the potlatch in indigenous society:

“…some were trained to make canoes, some to hunt, some to catch fish, some to dry fish, some to get material to make our clothes, then we divided this up amongst the others. This was the beginning of our feast of giving away.”

Section 149 of the Indian Act, which banned the potlach, was a challenge to enforce, both practically and legally. It was difficult to determine exactly what the potlatch was, under the law, and to prove when it was happening. In 1889, Chief Justice Begbie found the legislation on the potlatch to be lacking when it came to sentencing, stating:

“…if the legislature had intended to prohibit any meeting announced by the name of “potlatch” they should have said so. But if it be desired to create a new offence previously unknown to the law there ought to be some definition of it in the statute.”

The law was amended in 1895, and agents were particularly determined to prosecute those who were “incited to potlatch”, despite the lack of legal evidence in some cases, as demonstrated by William Halliday, agent to assistant deputy and secretary J. D. McLean in Ottawa. The methods of curtailing the potlach extended to holding meetings between agents and First Nations leaders, so that the agents could “read to them the specific article…and give reasons why the potlach should be condemned and done away with.” Agents deemed the tradition wasteful, leaving nations “near penury.”

After such a meeting, agent Halliday states:

“Yesterday and today they have been to a certain extent violating that section as they have been holding mourning ceremonies, part of which consists in singing mourning songs and part in receiving gifts from the surviving relatives, but I have not interfered with them in any way.”

Such accounts from agents and other departmental officials illustrate an attempt to monitor, control and suppress basic aspects of First Nations culture, even beyond the potlatch itself. This continued despite efforts by indigenous leaders to explain indigenous lifestyle and customs to government officials.

Potlatch, 1907 (MIKAN 3572940)

The great contrast among Chief Assu’s letter, Justice Begbie’s remarks and Agent Halliday’s account allows for a more complete understanding of the potlatch ban issue. Assu’s letter is straightforward in describing the potlatch and its importance. Begbie’s comments speak to the challenges in attempting to use legislation to control cultural practices. Halliday’s account provides insight into the mindset and practices of the Canadian government at the time. Having access to these multiple perspectives highlights the importance of archival records in researching complex historical issues.

Additional resources

Sveda Sparks worked at Library and Archives Canada’s Vancouver public service point in the summer of 2017 as part of the Federal Student Work Experience Program (FSWEP).