By Forrest Pass

This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

On July 20, 2021, British Columbia marks 150 years of provincehood. This photograph of Victoria unintentionally tells an often forgotten story about the new province-to-be on the eve of its entry into Confederation. In the background, across the Inner Harbour, we see a colonial frontier capital with the old government buildings, nicknamed “the Birdcages,” to the right and the warehouses and wharves of the commercial district to the left.

View of Victoria Harbour, about 1870, by Frederick Dally. (c023418)

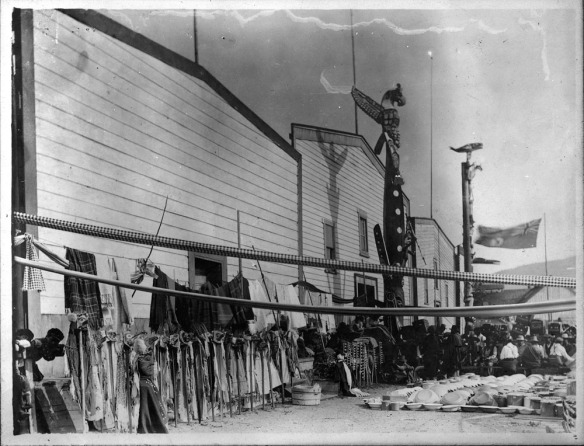

The foreground provides a different perspective. The buildings are the lək̓ʷəŋən (Lekwungen) village at p’álәc’әs (Songhees Point). The lək̓ʷəŋən people have lived in what is now Greater Victoria since time immemorial. Although he may not have intended it, photographer Frederick Dally captured an important truth: “British Columbia” in 1871 was, in fact, a series of First Nations and Métis Nation communities with a very small European settler one.

This fact influenced British Columbia’s entry into Confederation in unexpected ways. Documents in the collection at Library and Archives Canada record the British Columbia negotiators’ efforts to use the large First Nations population in the colony to their own advantage while simultaneously dispossessing those same Nations of their traditional territories and resources.

Vancouver Island had become a British colony in 1849. Nine years later, the discovery of gold in the Fraser River brought some 30,000 fortune seekers to the nearby mainland and prompted the organization of a second colony, British Columbia.

By the late 1860s, however, the gold rush had ended. The island and mainland colonies were united in 1866 as a cost-saving measure, and the settler population of united British Columbia dropped to about 10,000. Having spent a fortune on wagon roads and other construction projects, the government was almost bankrupt. The Canadian government sensed an opportunity and orchestrated the appointment of Sir Anthony Musgrave as British Columbia’s governor in 1869. Musgrave had served as Governor of Newfoundland and although he had failed to unite that colony with Canada, his commitment to Confederation was well known.

“View from the Morning House, Government House, Victoria,” watercolour by Frances Musgrave, about 1870. Frances’ brother, Governor Sir Anthony Musgrave, may have enjoyed a similar view when writing his dispatches on British Columbia’s proposed entry into Confederation. (c028380k)

On arriving in Victoria, Musgrave wrote to the British Colonial Secretary about the prospects of Confederation with Canada. Cost was a major obstacle. Governing a large but sparsely colonized territory was expensive and the annual federal subsidy of eighty cents per resident that all provinces received would be “insignificant” in British Columbia’s case.

Letter from Sir Anthony Musgrave to Lord Granville, British Colonial Secretary, describing the obstacles to Confederation, October 30, 1869: “The machinery of government is unavoidably expensive from the great cost of living which is at least twice as much as in Canada…” (RG7 G21 Vol 8 File 25a Pt 1, Heritage).

Insignificant, that is, unless Musgrave could justify a larger population estimate. This involved some creative math. In an 1870 letter to the Governor General of Canada, Sir John Young (later Lord Lisgar), Musgrave showed his work. British Columbia relied heavily on imported goods, so Musgrave divided the colony’s annual customs revenue (about $350,000, or $7.2 million today) by the per capita customs revenue of the eastern provinces ($2.75, or $56.51 today). By this calculation, British Columbia had a population of 120,000 rather than 10,000 for setting its annual subsidy and its representation in the Parliament of Canada.

To bolster his argument, Musgrave pointed to the First Nations population. After all, he noted, First Nations people in British Columbia were “consumers” and paid customs duties just as settlers did. Including First Nations people brought the real population closer to Musgrave’s creative calculation.

Remarkably, Canada’s negotiators agreed in principle, though the draft Terms of Union reduced the population estimate to 60,000. Nevertheless, when the Parliament of Canada debated the British Columbia agreement in March 1871, the opposition howled that by including First Nations people the Terms violated the principle of representation by population. “We have never given representation under our system to Indians,” complained Liberal leader Alexander Mackenzie. Similarly, David Mills, an Ontario MP, argued that First Nations people were not part of “the social bond, and could not stand on the same footing as the white population.”

But Musgrave never suggested that First Nations people should “stand on the same footing” as settlers. He did not believe that they should vote nor that they should benefit from that larger annual subsidy. In this sense, his formula was similar to the infamous clause in the Constitution of the United States that counted each enslaved person as three fifths of a person when calculating a state’s representation in Congress. Just as the three-fifths compromise used the enslaved population to increase the political influence of slaveholders, Musgrave’s formula increased British Columbia’s national influence without acknowledging the existing rights, title and sovereignty of the Indigenous majority.

Despite opposition objections, British Columbia became Canada’s sixth province on July 20, 1871. The correspondence on the subject in the Governor General’s records at Library and Archives Canada concludes with an official copy of the Terms of Union—a rare original printing of this important constitutional document. In his cover letter, the Colonial Secretary, Lord Kimberley, wished Canada and British Columbia “a career of progress and prosperity worthy of their great natural fertility and resources.”

An original printing of the British Columbia Terms of Union, with the Colonial Secretary’s cover letter to the Governor General of Canada (RG7 G21 Vol 8 File 25a Pt 1, Heritage)

First Nations people would not share much in that “progress and prosperity.” Under the Terms of Union, Canada agreed to follow “a policy as liberal as that hitherto pursued” when dealing with First Nations. This was a cruel joke, as neither pre- nor post-Confederation policy was particularly “liberal.” Except for the Douglas Treaties, a series of controversial land purchases around Victoria in the 1850s, the colonial governments of British Columbia had signed no treaties with First Nations. After Confederation, federal and provincial policy would result in the marginalization of First Nations and the Métis Nation in their own territories and communities. For example, the lək̓ʷəŋən residents at p’álәc’әs would move to another village site in 1911, to make way for the growing settler city. First Nations people were integral to Musgrave’s population formula, which had helped to convince British Columbia settlers to support Confederation with Canada. However, the province’s entry into Confederation was no cause for celebration for most Indigenous people in the region, an important point to remember as we observe the 150th anniversary.

Forrest Pass is a curator with the Exhibitions team at Library and Archives Canada.

![A handwritten page that reads, “On a Memorandum, dated 21st January, 1903, from the Minister of the Interior, stating that application has been made by the Minister of Justice for the transfer to his Department, for the purposes of the British Columbia Penitentiary of Goose Island, situated about the center of Pitt Lake, in Section 25, Township 5, Range 5, west of the Seventh Meridian, in the Railway Belt in British Columbia, the said island being required for the quarrying of stone thereon for use in connection with the penitentiary. The Minister recommends, as the land is vacant in the records of the Department of the Interior, that, under Clause 31 of the Dominion Lands Act, it be transferred to the Department of Justice for the purposes of the British Columbia Penitentiary as above mentioned. The Committee submit the same for approval.” [Signed by] Wilfrid Laurier.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/e008344308-07-v8.jpg?w=584&h=466)