By Andrew Horrall

In the early morning of October 24, 1944, one week before Halloween, Prime Minister Mackenzie King dreamed about close friends. King—who was fascinated by spiritualism—felt that his dream signified “the presence of relations interested in matters pertaining to myself, and wishing to let their presence be known” (WLMK diary, October 24, 1944, p. 1). During that day, King noticed further signs of otherworldly guidance, as he tried to resolve an issue that was splitting his government and the country.

At the start of the Second World War in 1939, King had promised not to introduce conscription, but now Canada’s army in Europe desperately needed reinforcements. King spent the afternoon chairing a heated discussion in Cabinet about whether to force young men into the military. He was especially annoyed when Thomas Crerar, the Minister of Mines and Resources, insisted that “Zombies ought to be sent overseas” to help end the war (WLMK diary, October 24, 1944, p. 8).

“Come On, pal … ENLIST!” recruiting poster, ca. 1942 (c087427k)

Modern readers might ask themselves, did the government debate sending one-time humans, transformed by infection into cannibalistic undead monsters, into battle? The answer is no. The Cabinet discussion reflected how wartime tensions had transformed the relatively uncommon term “zombie” into a popular Canadian colloquial expression.

Zombies appear in many contemporary movies, comics, books and television programs; however, in the 1940s, zombies were much more obscure and still firmly rooted in Haitian folklore as mindless, mute automatons raised from the dead to perform manual tasks. Most North Americans first heard about zombies in a bestselling 1929 book, The Magic Island, whose author claimed to have met actual zombies in Haiti. Hollywood adapted the book three years later into the first zombie movie: White Zombie. Bartenders also began mixing the “zombie,” a potent rum cocktail whose stupefying effects put people in mind of the addled creature.

The story of zombies in the Canadian army is more complicated. At the start of the war in September 1939, King pledged that he would not introduce conscription for overseas military service. The issue had split the country in 1917, and it threatened to do so once again. Volunteers were instead asked whether they agreed to fight overseas. In 1940, the National Resources Mobilization Act gave the government the power to conscript men, but only for service within Canada. Individuals still had to declare their willingness to become General Service, or “GS” men. Tensions between the two groups—the GS men and those who refused to serve overseas—soon became apparent at basic training stations throughout Canada. GS men derided those who had elected to serve in Canada as “Maple Leaf Wonders” for not accepting dangerous front-line posts. After completing their training, many GS men proceeded overseas, while those who remained at home undertook administrative

tasks and guarded Canada’s coasts.

Troops in basic training, Lansdowne Park, Ottawa (e010778708)

Ongoing political, social and military tensions about conscription resulted in a national plebiscite in April 1942, in which English Canadians voted to give the government the power to force men to fight, while French Canadians opposed the idea in equal numbers. The deep divisions were apparent to King, who tried to chart a middle ground under the slogan “conscription if necessary, but not necessarily conscription.”

James S. Duncan, President and General Manager of the Massey-Harris Company, urging workers to vote in favour of conscription in the forthcoming national plebiscite, 1942 (a164429)

By early 1943, men who refused to fight overseas were being ridiculed as “zombies” by GS men, women in uniform and the public at large. It is not clear when the insult was first used to depict these men as cowardly, passive and unable to think for themselves. The image was reinforced by English-Canadian newspapers and magazines, which reported on how zombies were the target of jokes and were linked to supposedly subversive elements in Canadian society, and how women refused to date zombies. A photograph in the Toronto Star in January 1943, showing a group of shipyard workers who had painted zombie faces on their welding masks, suggests that some men were proud of their decision not to fight and embraced the supposedly degrading term (“Shots behind scenes in Canada’s war factories,” Toronto Star [January 13, 1943], p. 17).

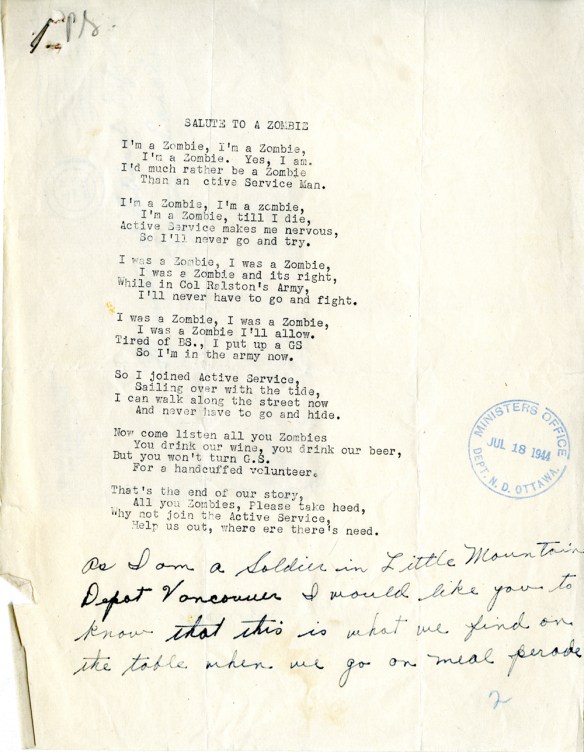

The idea of zombies was seared into the Canadian imagination in July 1943 by reports about a riot at a Calgary military base. Fighting broke out there after GS men taunted those who refused to serve overseas with “Salute to a Zombie,” a song that appears to have been commonly heard across Canada. The copy sent to Colonel J.L. Ralston, the Minister of National Defence, who strongly advocated sending zombies overseas, is preserved at Library and Archives Canada.

By the time King chaired the Cabinet meeting a week before Halloween in 1944, he faced intense pressure from ministers, military commanders and large sections of the public to send zombies into combat, because Canadian army casualties could no longer be replaced by volunteers alone. King resisted until November, when he decided to compel some 17,000 zombies to go overseas, causing a wave of desertions and a short-lived mutiny in British Columbia. In the end, about 2,500 zombies fought in Europe, where 69 of these soldiers died.

A generation of Canadians, mostly in English Canada, associated zombies with bitter social divisions caused by the Second World War. The term’s modern meaning and the creature’s prominent status in popular culture dates to the release of the 1968 film Night of the Living Dead.

Andrew Horrall is a senior archivist in the Private Archives Division at Library and Archives Canada.

Wow! Interesting stuff – who knew?

Pingback: You’re on the Wrong Beach, Zombie! | OneTubeRadio.com

I found this relatively interesting given a larger interest in both Canadian and military history. I was directed here from a short story referencing this one.

I do believe it could use a most beneficial edit with respect to this former Prime Minister’s name. In as much as his full name was William Lyon Mackenzie King, his surname was Mackenzie King, vs the oft incorrectly abbreviated King. Even the Library and Archives Canada gives his surname as Mackenzie King. There is little need to use or publish it incorrectly as the US President of the day did.

Thank you for posting the piece. I look forward to this update.

Thanks for the info. We will look into it.