By Emily Potter

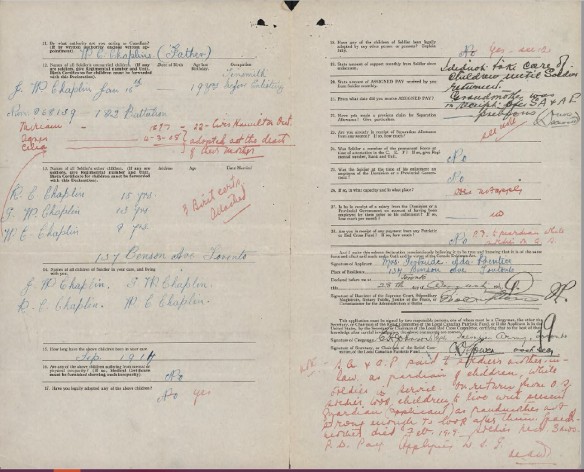

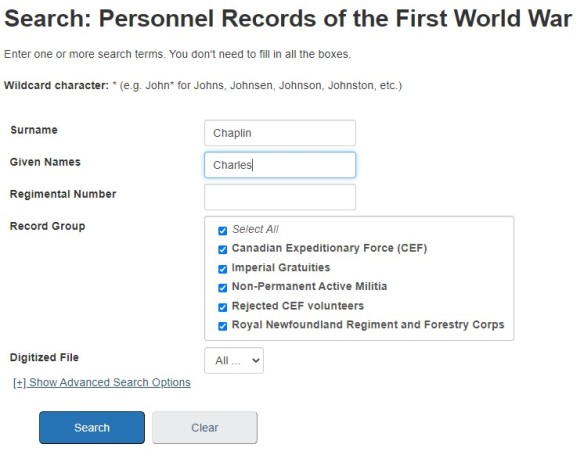

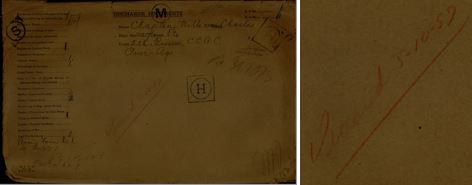

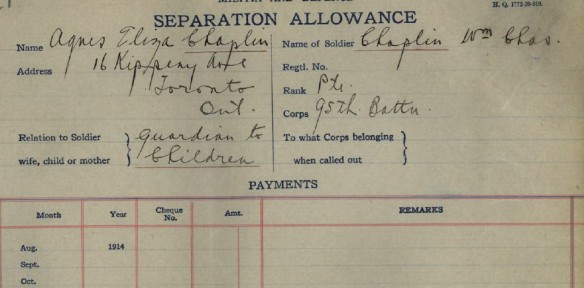

In Part I of this blog article, we explored how to start your genealogy research using a First World War file. I chose a random name to search in Library and Archives Canada’s (LAC) Personnel Records of the First World War database and selected the file of William Charles Chaplin. From his First World War file, we found out the following genealogy information about him:

- Date and place of birth: June 23, 1870, Chatham, Kent, England

- Date and place of marriage: Unknown

- Date and place of death: October 5, 1957, place unknown

- Mother’s name: Unknown

- Father’s name: Unknown

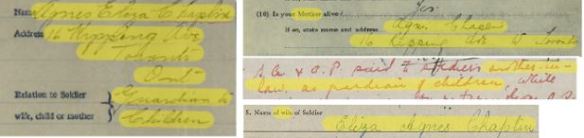

- Spouse’s name: Eliza Agnes Turton, daughter of Agnes Eliza; died before March 2, 1916

- Children’s names: Miriam, James, Richard, George, Agnes, William, and Celia

Now, let’s see whether we can fill in some of those unknowns by searching other genealogy sources held at LAC.

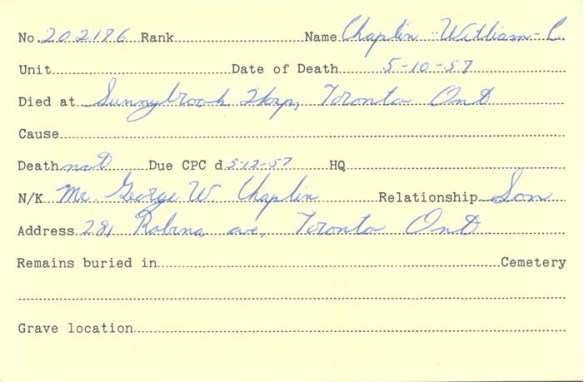

Veterans Death Cards

I’m going to start at the end and see whether we can find out where Chaplin died by searching the Veterans Death Cards. Created by Veterans Affairs Canada, Veterans death cards—although ominous sounding—are index cards that include information about a First World War veteran’s death, such as the date and place of death and the next of kin. They usually also indicate whether the death was a result of the veteran’s military service.

Although a very helpful resource, the cards have limitations. There is not a card for every First World War veteran because Veterans Affairs was not always notified of the death. Moreover, the cards include only deaths that occurred up to the mid-1960s.

By following these instructions, I was able to find the card for William Charles Chaplin:

We know this is the correct card, because the regimental number and the date of death match those we saw on the envelope in Chaplin’s file, as discussed in Part I.

We now know that Chaplin passed away in Toronto. The line that reads, Death not, indicates that his death was not attributed to his First World War service.

Census

Now that we’ve searched the Veterans Death Cards, let’s explore another important genealogy research tool: censuses. Census returns are official Government of Canada records that enumerate the country’s population. They are an invaluable source of information for genealogy research because they provide details about each person in the household, such as age, country or province of birth, ethnic origin, religious denomination and occupation. In some years, the census also indicates the year of immigration.

We already know that Chaplin was born in England, but the 1911 census may help us find out when he immigrated to Canada, as Chaplin was in Canada by the start of the First World War.

After a few tries, I found a reference to Chaplin and his family by using the search terms seen in the image below.

Search screen of the 1911 Census database.

1911 Census database, W Charles Chaplain.

Chaplin’s name in the census appears as “W Charles Chaplain.” This serves as an excellent example of how common spelling variations can be in older documents. If you’re having trouble finding reference to your ancestors in the census, see Research Tips on our census page for help with name and place searching.

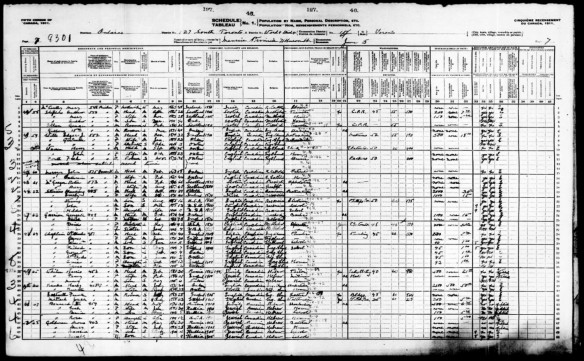

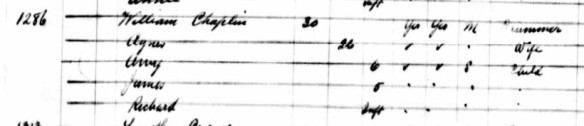

Let’s have a closer look at the census image.

1911 Census, Toronto, Ward 4, page 7 (e002028460).

As we can see from the above image, the family immigrated to Canada in 1904. From what we saw in Part I, Miriam (or Marian) was the eldest child, born in 1898 or thereabouts. In this census, we see reference to a child by the name Annie, or Amia. The year of birth indicates that it is likely this is in reference to Miriam. The name we see here could have been a middle name, a nickname or an error, and we already know how common it is to see name variations in older records. Regardless, from this census, we gather that Annie/Amia/Miriam/Marion was born in England, along with her siblings James and Richard, whereas Agnes, William, Charles and George were all born in Ontario. This suggests that William and Agnes were most likely married in England, not in Canada. Their first child was likely born in 1898. Therefore, they were likely married that year or earlier.

Passenger lists

The census indicated that the family immigrated to Canada in 1904. Can we confirm this information?

Library and Archives Canada has several immigration databases, all of which are listed on LAC’s Ancestor’s Search page. For this search, we will be using the Passenger Lists for the Port of Quebec City and Other Ports, 1865-1922 database.

From the database search screen, I searched using only his first and last names. I chose not to enter a year of arrival to keep the search as broad as possible to start.

Luckily for me, there were only eight results, and the first one was in reference to our William Chaplin.

Reference page from the Passenger Lists for the Port of Quebec City and Other Ports, 1865-1922 database for William Chaplin.

As we can see, the family actually arrived in 1905, not in 1904. This is no surprise, because, as we learned in Part I, it is quite normal to see discrepancies in older records.

Detail of passenger list showing William Chaplin’s arrival on the S.S. Dominion to Halifax, RG76, microfilm reel T-499.

William Chaplin, his wife, Agnes, and their three children are listed. Once again, we see Miriam’s name listed under a variation; in this case, it looks like “Amy.” Amy would have been born in 1898. This matches what we saw in the census and in the First World War file for Miriam.

Other than an additional name variation, the passenger list did not add to our list of missing information, but it did confirm the date on which the family immigrated.

- Date and place of birth: June 23, 1870, Chatham, Kent, England

- Date and place of marriage: England, likely 1898 or earlier

- Date and place of death: October 5, 1957, Toronto, Ontario

- Mother’s name: Unknown

- Father’s name: Unknown

- Spouse’s name: Eliza Agnes Turton, daughter of Agnes Eliza; died before March 2, 1916

- Children’s names: Miriam, James, Richard, George, Agnes, William, and Celia

Reviewing our list of information on William Charles Chaplin, we see that we have added that his place of death was Toronto, Ontario, and that he was likely married in England in 1898 or earlier. We also learned more about his family, such as approximate birth dates, the country and province of birth for each family member, and the date on which the family immigrated to Canada.

That being said, we are still missing some key details about Chaplin, primarily… who were his parents?

At this point, we’ve searched through the primary genealogy sources held at LAC, but many other helpful genealogy sources are maintained by other institutions. We won’t search them here, but I’ll outline what my next research steps would be if I were to continue researching Chaplin and his family.

Civil registration

In order to find out the names of Chaplin’s parents, my first step would be to look for his marriage record. Civil registration records are extremely helpful genealogy sources, and both birth and marriage records usually indicate parents’ names.

I would start with Chaplin’s marriage record since we know his wife’s name. This will help us to identify the correct record. If we were to start with his birth record, we would have no means of knowing whether we had found the correct William Charles Chaplin or simply another baby with the same name.

We know that Chaplin was married before he immigrated to Canada. So, we would need to search English records.

British birth, marriage and death records are held at the General Register Office (GRO) in England. The indexes to those records are arranged by year and can be searched on various websites, including FreeBMD.

We could also find out more information about Chaplin’s family by searching civil registration records for each family member. In Canada, the civil registration of births, marriages and deaths is a provincial and territorial responsibility. As a federal institution, LAC does not hold those records. Information about the records, including how and where to access them, can be found on our Places pages, which include resources for each province.

There is definitely a lot more genealogy research we could do on William Chaplin and his family, but after reading these two blogs, I bet you’re itching to get started on your own research.

Information about how to start your family history research can be found on LAC’s How to Begin page.

Finally, don’t forget LAC’s Personnel Records of the First World War database, which you can search for references to your ancestor’s service in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Thanks for reading!

Emily Potter is a genealogy consultant in the Public Services Branch of Library and Archives Canada.

Tags: William Charles Chaplin, genealogy, immigration, passenger list, S.S. Dominion, census, 1911 Census of Canada, Veterans Death Cards

![A typed and handwritten document, titled Particulars of Family of an Officer or Man Enlisted in C.E.F. [Canadian Expeditionary Force], from William Charles Chaplin’s service file in the Personnel Records of the First World War database.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2021/08/pic9.jpg?w=584)