This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

by Heather Campbell

The Canadian Eskimo Arts Council (CEAC) was created through funding from the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs in 1961 as a solution to the perceived problem of declining quality in Inuit art and a need for a system to approve images for the new Inuit printmaking practice. The CEAC assumed responsibility for creating a jury to select prints for annual Inuit print collections, primarily in Cape Dorset and Baker Lake, Northwest Territories (now Nunavut). It also launched the internationally celebrated Masterworks exhibition, which toured internationally between November 1971 and June 1973. The CEAC brought Inuit art to the world stage and assisted in the expansion of the Inuit art market. It helped shape what we know as Inuit art today.

The Canadian Eskimo Arts Collection was transferred to Library and Archives Canada in 1991. The collection consists of various operational documents, reports, copyright requests, correspondence, audio recordings of meetings, interview transcripts and documents related to the Masterworks exhibition (also known as Sculpture/Inuit). The collection provides insight into how the Inuit art market was developed from the 1960s to the late 1980s. The CEAC was in charge of approving annual print collections for the Cape Dorset Eskimo Arts Council, and other collections from communities such as Ulukhaktok (formerly Holman) in the Northwest Territories, Pangnirtung in present-day Nunavut, and Povungnituk and Inukjuak in Nunavik (northern Quebec). The CEAC also created the Igloo Tag program, which authenticated Inuit sculptures through a tag or sticker affixed to artwork that included information about the artist (see last image in blog).

In addition to the textual documents in the collection, there is also an extensive collection of Inuit art print and sculpture catalogues, organized by community, as well as audio recordings of conferences and workshops related to sculpture and prints. In these recordings in particular, we hear the concerns of Inuit artists first hand and can better understand the dynamics between the artists and the CEAC. For example, when reading through reports regarding site visits, we learn that they met with artists who wanted their artwork promoted in the south and whose work was deemed marketable. We can read the general criteria for the acceptance or rejection of certain prints. When combing through the minutes or correspondence, we get an idea of the artistic tastes of the CEAC and see why certain artworks were not deemed suitable for promotion.

When seen in its entirety, we recognize the CEAC as a symbol of its time and the prevailing societal attitudes toward Indigenous peoples and their artwork. When we read through the interviews with artists in particular, we start to notice a distinct difference between what the CEAC members considered “good” Inuit art and what the artists themselves thought was “good” art. Generally speaking, Inuit also valued art that was representational and well finished. They did not share the same appreciation that many collectors and CEAC members had at the time for sculptures that were not well finished and were perceived by southerners as “primitive.”

The CEAC influence over Inuit art helped to create a certain “primitive” aesthetic that was, one could argue, not fully representative of the traditional aesthetic of Inuit culture. For example, reading through interviews with artists from Nunavik, we can see that they were baffled as to why the works of some artists were so popular with people in the south. Why were so many Inuit artists forced into this repressive and inauthentic paradigm? In many cases, an Inuit artist was just that—not an individual with his or her own sense of what was aesthetically pleasing or worth expressing on paper, in stone or through whatever material the person deemed fit. As illustrated in the image below from a Government of the Northwest Territories pricing brochure, only “traditional” materials were bought by the wholesalers. Today, we would not dream of imposing these types of restrictions on a non-Indigenous artist living in downtown Toronto, for example, but during that time, this imposition on Indigenous artists was prevalent. Thankfully, there were CEAC members who opposed this approach, but it has taken decades for the expectations of the Inuit art world to change, to set aside this anthropological lens and to be receptive toward artistic expressions by Inuit artists as individuals, rather than as representatives of some collective Inuit consciousness.

On this subject, Natan Obed, President of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, stated in his keynote speech at the 2019 Inuit Studies Conference:

The right to be diverse in society is something that we are fighting for. . . . We don’t have to always have these straw polls about whether or not an Inuk can create something and if that creation is in line with the expectations that the society has. Or a person can be of any faith. A person can reject or take on Inuit traditions, Inuit history. You can be a computer programmer just as much as you can be a hunter. That’s not to say that we’re not encouraging Inuit to live healthy lives within Inuit Nunangat and do traditional things; it’s to say that when Inuit do not feel that that is their path, that we somehow are able to not have those conversations that demean them, that put them down, and that “other” them when it is their right in a society as a peoples to do whatever it is that they feel that they want to do with their lives.

A large contributing factor to the creation of this definition of Inuit art was the fact that formal governance of our own art did not exist in the early years of the art movement. There was minimal communication between the artists themselves and those marketing and selling their art. And without meaningful conversations about the nature of art making, how can true understanding be achieved? How could the practical needs of artists be met if they were not being asked what they truly needed? The CEAC did not have an Inuk member until 1973, with the appointments of Joanasie Salomonie (1938–1977) and Armand Tagoona (1926–1991), who both resigned before ever attending a meeting. Other appointments followed over the last few years of the CEAC.

It was not until the formation of the Inuit Art Foundation (IAF) in 1988 that a governing board was created that consisted of a majority of Inuit artists, beginning in 1994. A concerted effort was made by the IAF to train Inuit artists in art marketing, promotion and copyright. In 1995, the IAF created the Cultural Industries Training Program, which taught students Inuit art history and gave an introduction to exhibition design. Thanks in part to the IAF and its programming, Inuit slowly began to enter the arts administration sector. In 1997, July Papatsie, one of the first Inuk curators, co-curated the internationally touring exhibition Transitions at the Indian and Inuit Art Centres (now the Indigenous Art Centre) of the former Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (currently Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada). In 2015, Heather Igloliorte became the first Inuk to edit an issue of the IAF’s Inuit Art Quarterly.

In 2017, the IAF took over the administration of the Igloo Tag Inuit art authentication. For the very first time in 2018, licensee status was given to an Inuit-owned gallery: Carvings Nunavut Inc., belonging to Lori Idlout of Iqaluit. Inuit are finally in the position of saying when a piece of art is genuine Inuit art! Also in that year, four Inuit guest curators—Kablusiak, Krista Ulujuk Zawadski, Asinnajaq and Heather Igloliorte—were selected to curate the first exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery for the former Inuit Art Centre, recently renamed Qaumajuq, which is set to open in February 2021. Inuit are opening, expanding and leading discourse about our own artistic expressions, and I look forward to seeing what the next 50 years hold for the Inuit art world.

These related collections are also found at Library and Archives Canada:

- Charles Gimpel fonds: includes photographs of artists and Cape Dorset Print Shop

- Rosemary Gilliat Eaton fonds: includes photos of artists and Cape Dorset Co-operative

- Judith Eglington fonds: includes photos of artists and Cape Dorset Co-operative

This blog is part of a series related to the Indigenous Documentary Heritage Initiatives. Learn how Library and Archives Canada (LAC) increases access to First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation collections and supports communities in the preservation of Indigenous language recordings.

Heather Campbell is an Inuk artist originally from Nunatsiavut, Newfoundland and Labrador. She was a researcher on the We Are Here: Sharing Stories team at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg)

Thanks for this important story. The IAF was long overdue… Bravo!

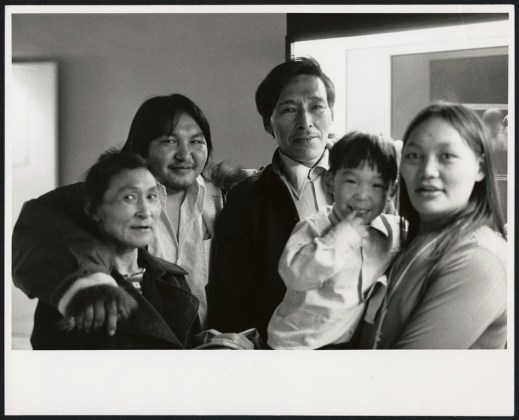

fabulous article! my adopted son’s birth uncle is Andrew Qappik, a well known Inuit print artist, and I knew Ruby (from the picture). Thanks for this great story.

Pingback: The Canadian Eskimo Arts Council — Defining Inuit art — Library and Archives Canada Blog | Ups Downs Family History

Pingback: Library and Archives Canada Blog – Featured Blogger of the Week November 12, 2021 | Ups Downs Family History

Pingback: Gone Fishing . . . for a New Inuit Print | by Cleveland Museum of Art | CMA Thinker | May, 2022 – marthafied

Pingback: Gone Fishing . . . for a New Inuit Print | by Cleveland Museum of Art | CMA Thinker | May, 2022 - Themonet-ART

Pingback: رفته ماهی گیری. . . برای چاپ جدید اینویت موزه هنر کلیولند | متفکر CMA | می 2022 – shahinshahrhonar

Pingback: Gone Fishing . . . for a New Inuit Print | by Cleveland Museum of Art | CMA Thinker – Archelle Art

Pingback: Gone Fishing . . . for a New Inuit Print | by Cleveland Museum of Art | CMA Thinker – Michael Armitage

Pingback: Gone Fishing . . . for a New Inuit Print | by Cleveland Museum of Artwork | CMA Thinker - Shareyday

Pingback: Gone Fishing . . . for a New Inuit Print | by Cleveland Museum of Artwork | CMA Thinker