By Caitlin Webster

Please note that some of the terms used and documents displayed in this article may contain language that is outdated, insensitive or offensive.

The late 19th century saw thousands of people flock to British Columbia, but few were as remarkable as John Freemont Smith. With an enthusiasm for his new home and a determination to succeed, he flourished as a businessperson, a municipal and federal official, and a civic volunteer. His accomplishments were all the more outstanding given that he was a Black man in a white settler community. He endured racism throughout his life while also earning respect and admiration from his contemporaries. Library and Archives Canada (LAC) holds many records relating to Smith’s work as the Indian Agent for the Kamloops Agency from 1912 to 1923, and a selection of these documents has been prepared as a Co-Lab challenge.

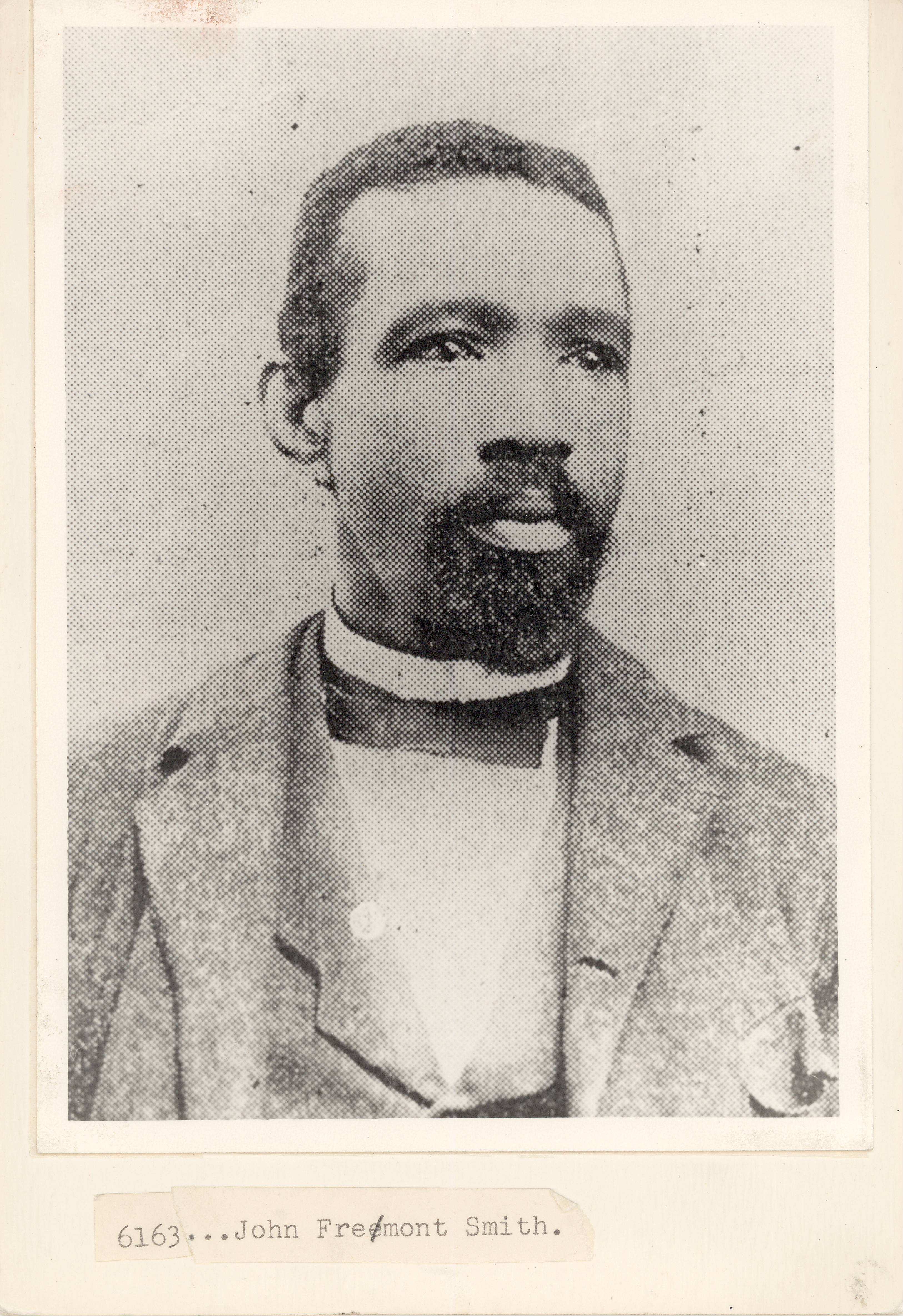

John Freemont Smith, ca. 1870s. Credit: Kamloops Museum and Archives KMA 6163

John Freemont (also spelled Fremont) Smith was born in Saint Croix on October 16, 1850, a few years after slavery was abolished in the Danish West Indies. He received his education and training as a shoemaker in Copenhagen and Liverpool before travelling through Europe and South America. He arrived in Victoria, British Columbia, in 1872, set up a shoemaking business, and in 1877, he married Mary Anastasia Miller.

John Freemont Smith and family, including wife Mary and children Agnes, Louise, Mary, Leo and Amy, ca. 1907–1910. Credit: Kamloops Museum and Archives KMA 10008

After brief stays in New Westminster and Kamloops, the family settled in the Louis Creek area in 1886. There Smith set up a store, prospected for minerals and dabbled in freelance journalism. He also served as Louis Creek’s first postmaster, a position he held until 1898.

That year, a fire destroyed the Smith home in Louis Creek, and the family relocated to Kamloops.

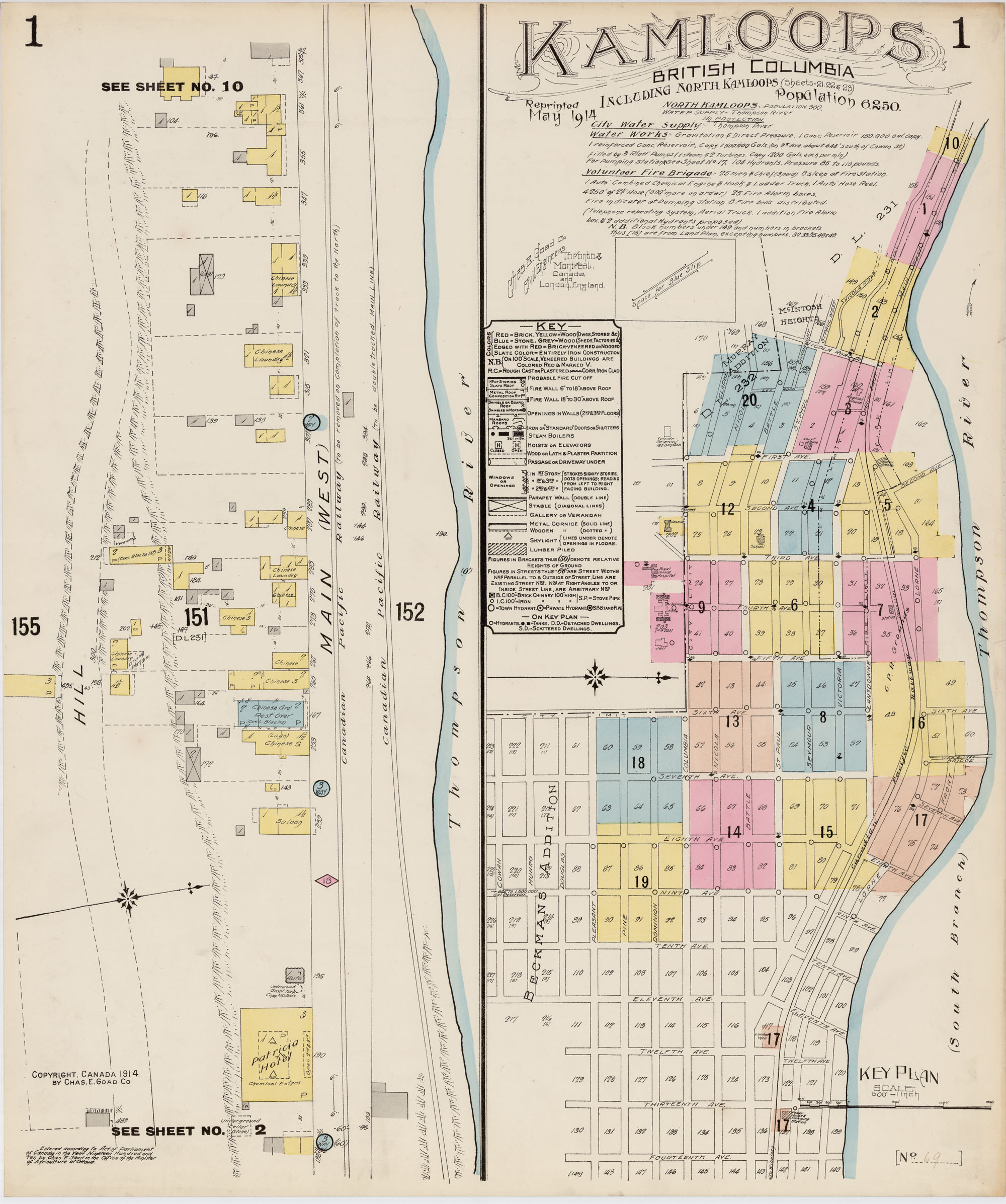

Fire insurance plan of Kamloops, British Columbia, May 1914 (e010688881-v8)

Smith continued to thrive in Kamloops, serving as alderman from 1902 to 1907, and as city assessor in 1908. He was also active in the community in other ways, helping to organize groups such as the local Agricultural Association, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the Conservative Association, and the Kamloops Board of Trade, where he served as secretary for several years. In 1911, Smith constructed the Freemont Block building on Victoria Street in Kamloops, which still stands today.

Kamloops City Council of 1905: Alderman J.F. Smith, Alderman D.C. McLaren, Alderman R.M. MacKay, Mayor C.S. Stevens, Alderman J.M. Harper, Alderman J. Milton and Alderman A.E. McLean; in background: J.H. Clements and William Charles; taken at the corner of Victoria Street and 3rd Avenue. Credit: Kamloops Museum and Archives KMA 2858

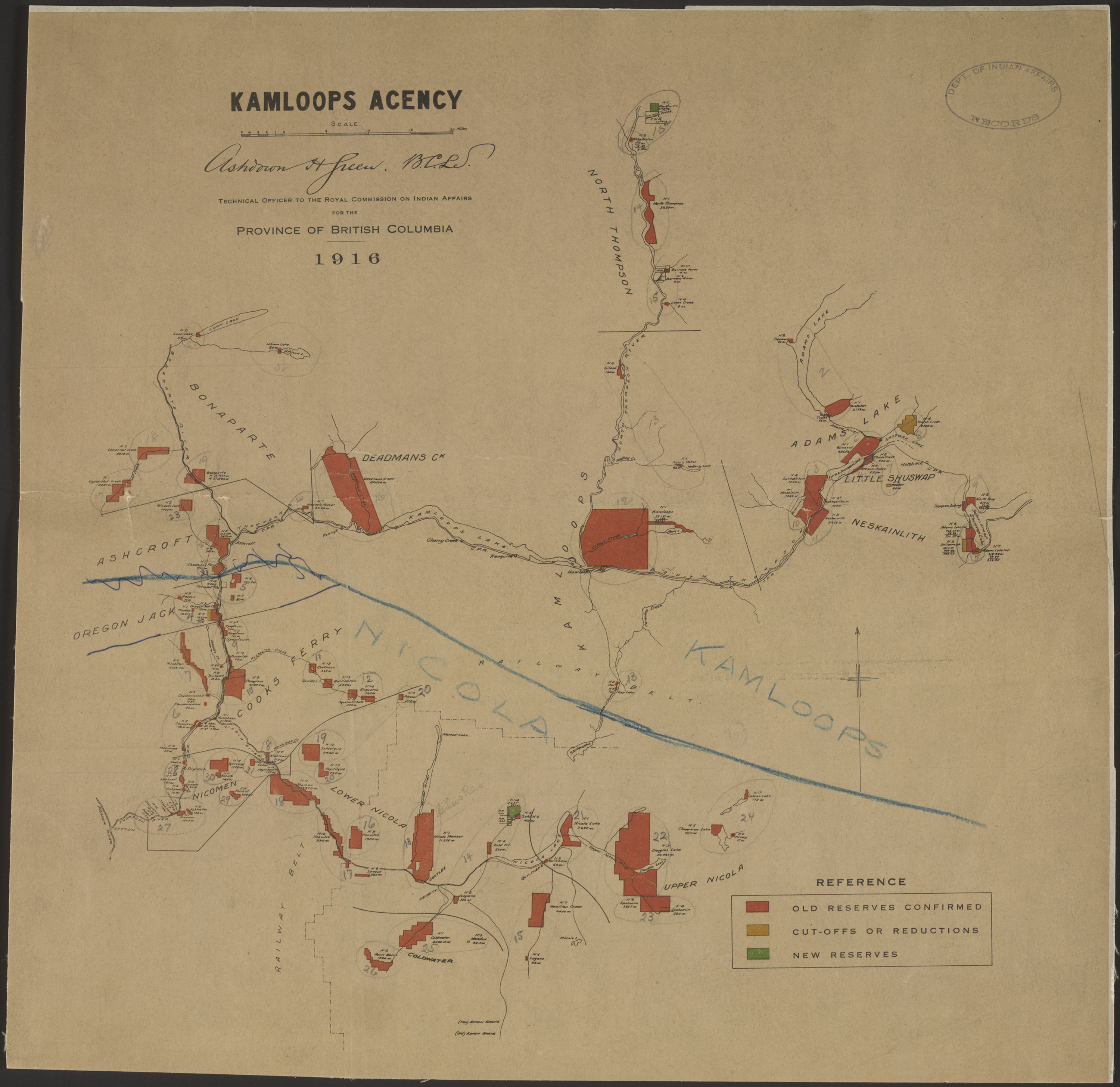

In 1912, at the age of 62, Smith was appointed Indian Agent for Kamloops, a position he held for over a decade. Smith took this role at a challenging time. His predecessor was generally considered ineffective and absent, and the interests of the local First Nation, the Secwepemc, suffered even further as a result. In addition, the Royal Commission on Indian Affairs for the Province of British Columbia was established in 1912. Commonly known as the McKenna-McBride Royal Commission, it had a significant impact on First Nations land bases by adding to, reducing or eliminating reserves throughout the province. Some of Smith’s earliest tasks as Agent were to travel throughout the sprawling agency to collect data for the commission, and then to advocate for the Secwepemc against attempts to cut off the most valuable portions of their reserve lands.

Kamloops Agency, 1916 (e010772172)

In addition, Smith’s situation was complicated. As a Black settler in a predominantly white society, he experienced racism from many in his community. Yet his task as Agent was to carry out the Canadian government’s policy of assimilation for Indigenous peoples. As shown by the 1910 general instructions given to new Agents in British Columbia, the goal was to steer the Secwepemc toward farming and ranching rather than their traditional ways of living, implement a Western system of separate land plots for each family instead of collective land, and encourage an ideal of individual independence over values of mutual aid.

Page six of a “copy of general instructions to newly appointed Indian Agents in British Columbia,” 1910 (e007817641)

Given Smith’s status and work, it is likely he was not naïve about the nature of these policies, as implementing them would be a requirement of any Agent. This resulted in a complex situation: a racialized individual imposing assimilation policies on another racialized community, on behalf of a colonial governance system. It is evident throughout Smith’s time as an Agent, however, that he approached the work with intelligent pragmatism, an outstanding work ethic and a spirit of advocacy for the Secwepemc.

The vast size of the Kamloops Agency and a constant lack of funds were two overarching challenges of Smith’s tenure as Agent. Additionally, the difficulties of encroaching settlement and its resulting strain on reserve land and irrigation were issues that plagued Smith throughout the 11 years that he held the position. From Smith’s earliest Royal Commission testimony to his reports that were logged a decade later, LAC’s holdings show the frustrating dilemma he faced. His task was to implement a policy to encourage farming and ranching, but there were few financial resources to help move this goal forward. Meanwhile farmers, ranchers and corporations from the settler community diverted water sources, trespassed on Secwepemc territory and lobbied for the removal of desirable lands from reserves.

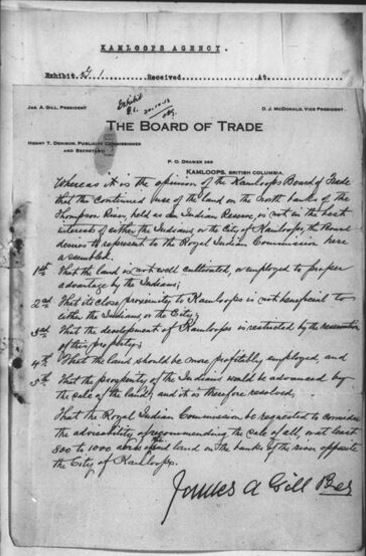

An example of this pressure was the continual vigilance and advocacy required to protect and retain Kamloops Reserve No. 1, which was situated directly across the Thompson River from the city of Kamloops. Prominent individuals in the city lobbied for the removal of the Secwepemc from the reserve as well as the subsequent sale of the land. Attempts during Smith’s tenure as Agent included a submission by the Kamloops Board of Trade to the Royal Commission in 1913 arguing that the Secwepemc would be better off if they sold the land and moved away from Kamloops, and that the city could more readily expand with the removal of the reserve.

Application to the Royal Commission on Indian Affairs for British Columbia by the Kamloops Board of Trade, to sell all or most of Kamloops Reserve No. 1 (RG10 volume 11021 file 538C from Canadiana Héritage)

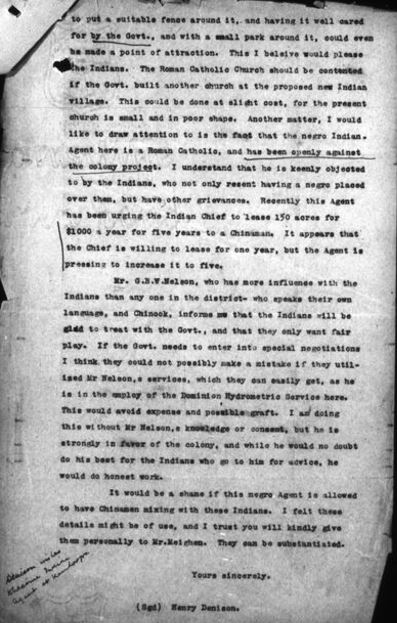

An additional attempt took place in 1919 when Henry Denison, secretary of the Kamloops branch of the Canadian Patriotic Fund, put forward a proposal to use the land as a settlement colony for soldiers returning from the First World War. Unsurprisingly, Smith opposed the renewed bid to obtain the reserve land. This elicited a racist response from Denison in a letter to Member of Parliament H.H. Stevens claiming, without evidence, that the Secwepemc resented having a Black man serve as Agent.

Page two of a letter from Henry Denison to H.H. Stevens, expressing racist and anti-Catholic views (RG10 Volume 7538 File 26 154-1 from Canadiana Héritage)

These experiences, as well as his wealth of knowledge of local politics and officials, made Smith well placed to identify unfair tactics used against the Secwepemc. Acquainted with the cronyism operating in many small towns, Smith could spot the discriminatory practices of some local governments. For example, while attempting to have a peddler’s fee refunded to Chief Titlanetza of the Cook’s Ferry Band, Smith explained the approach of one municipal government: “It is common property that the overhead maintenance charges of the City of Merritt are considerably maintained from money extorted from Indians in fines and other methods.”

Smith continued as Agent until 1923, and he remained in Kamloops for the rest of his life. He continued to write for the local newspaper and carried on with his volunteer duties in civic organizations such as the local Rotary Club. Smith died at his office in the Freemont Block on October 5, 1934.

Co-Lab is LAC’s online tool to tag, transcribe, translate and describe digitized holdings on our website. To commemorate Black History Month, LAC has created a Co-Lab challenge to transcribe records relating to John Freemont Smith’s work as the Kamloops Agent. Please note that some of the documents in this challenge may contain language that is outdated, insensitive or offensive.

To learn more about John Freemont Smith and the lives of the Secwepemc at the time, check out the following resources:

- P. Trefor Smith, MA thesis: “‘A very respectable man’: John Freemont Smith and the Kamloops Agency, 1912–1923” (PDF)

- Ronald Eric Ignace, MA thesis: “Kamloops Agency and the Indian Reserve Commission of 1912–1916”

- Kamloops This Week article by Jessica Klymchuk: “‘Spirit of a true pioneer’”

- BC Booklook article by Michael Sasges: “Grappling with Indian apples”

- CFJC Today article by James Peters: “Time capsule to commemorate historic Kamloops councillor, mark this moment in history”

Caitlin Webster is a senior archivist in the Reference Services Division at the Vancouver office of Library and Archives Canada.

Very revealing and well supported. This is an issue that never ends without decisive action driven by kindness, compassion, and appropriate legislation.

As an interesting aside, I have recently (Jan 2024) completed a renovation of the Indian Affairs office in the Old Federal Building (1900) in Kamloops BC – not the first time my path as an artist and cultural worker in Kamloops intersects JF Smith’s traces!

The building is now known as ‘Old Federal Studios’; here is the fb page for those who would like to see the images of the building and renovations:

https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?vanity=61551800592910&set=a.122115437306060019

Thank you for this post, which I find immensely interesting!

Vaughn

Kamloops BC

Thank you so much for reading this blog post, and for sharing images of this beautiful renovation. Can’t believe that ceiling was hidden.

A fascinating introduction to the story of the Federal Building and the Agent Fremont ~ thank you for the billets to follow up further

Glad you enjoyed this blog post. Thank you!