By Marc St. Dennis

This article contains historical language and content that may be considered offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

The Day Schools Project at Library and Archives Canada aims to identify, digitize, and describe records related to the federal Indian Day Schools (hereafter Day Schools) system, making them more accessible for survivors, their families, and researchers. Many First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Nation children attended these schools, which were part of a broader system of colonial assimilation policies. The first federally funded Day Schools were established in the 1870s, with the last closing or transferring to community control in the early 2000s. The Day Schools Project began in 2022 and is set to conclude in 2026.

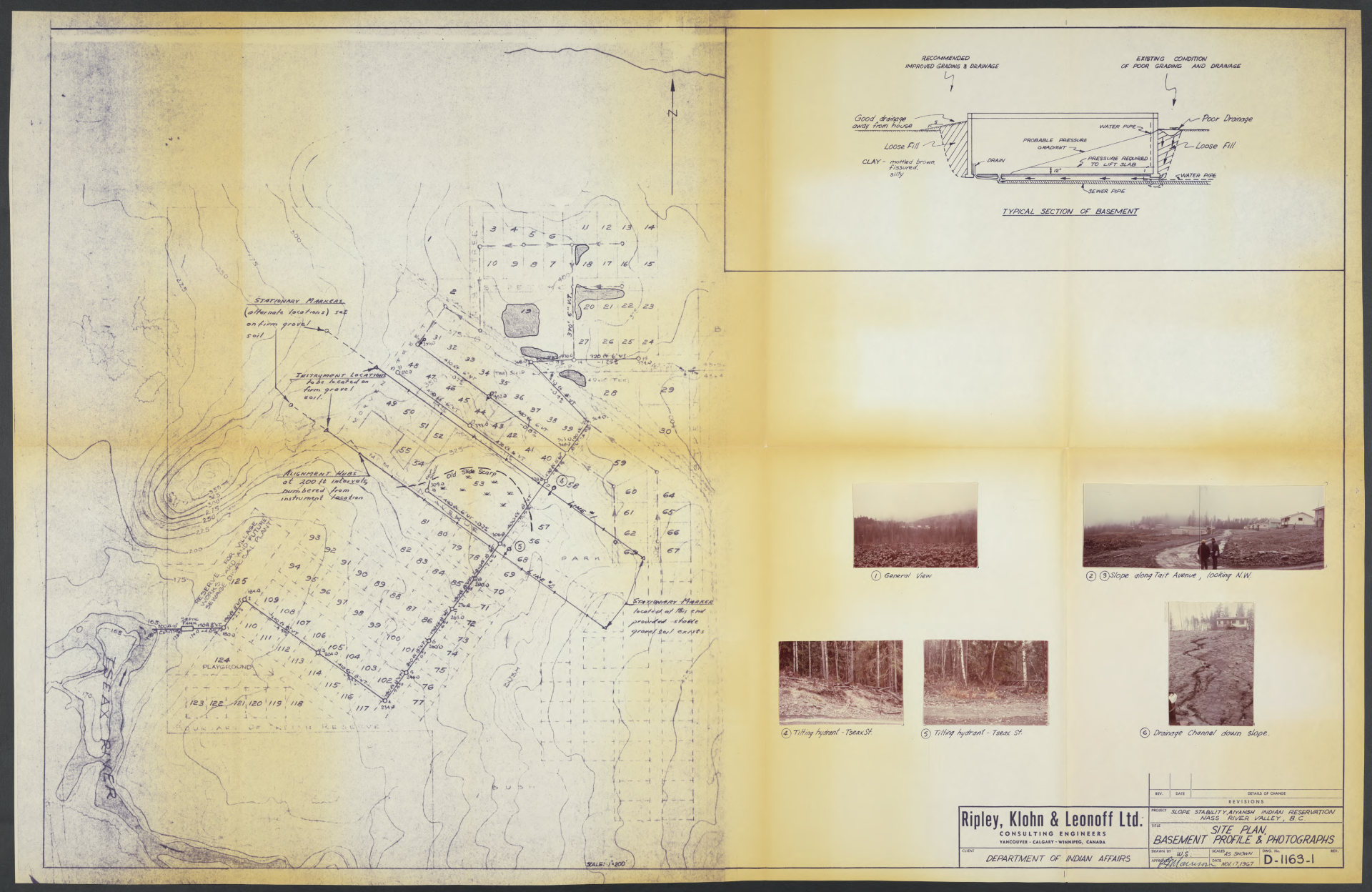

Site and technical plans and photographs of Aiyansh Day School, near Terrace, British Columbia, 1967, RG22, box number 10, file number 2909. (e011814153)

As an archivist working on this project, I spend my days digging through historical records—some fascinating, some routine, and some that carry the weight of the past. If you’ve ever wondered what kinds of documents are tucked away in these files, you’re in the right place.

Researching Day Schools can feel a bit like detective work. You open a file hoping for a clear answer, but instead find administrative reports, financial records, health records, and maybe even a surprise or two—like a hand-drawn school layout sketch on the back of an old memo. The key to understanding these records is knowing what types of documents exist and what they can tell us.

Uncovering Injustices in the Records

While some records may seem routine, they often reveal deeper injustices. Day Schools were part of a system that sought to assimilate First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Nation children, often through harsh discipline, inadequate resources, and a disregard for students’ well-being. Unlike Residential Schools, Day School students returned home (parental or other) in the evenings, but this did not mean they were spared from mistreatment, neglect, or abuse.

Inuit children in front of a nativity scene, Pangnirtung Day School, Nunavut, between 1950 and 1960, Joseph Vincent Jacobson and family fonds. (e011864991)

Many former students recall physical, emotional, and even sexual abuse at these schools. Some files contain evidence of these injustices, including complaints made by parents, records of punishments, or internal reports on misconduct. However, it’s important to recognize that records often reflect the institutional bias of school staff and the federal government. School administrators, teachers, and government agents were more likely to document disciplinary actions in ways that justified their own behaviours rather than acknowledging harm done to students. Reports may downplay or dismiss allegations of abuse, and language in official records often reflects the prejudices of the time, portraying Indigenous students as problematic or difficult rather than victims of systemic mistreatment.

Similarly, events and policies described in these records may be framed in a way that serves the interests of the government rather than reflecting the true experiences of students. For example, improvements in school conditions may be presented as sufficient responses to systemic neglect, even when students continued to face serious hardships. Researchers must approach these documents critically, understanding that what is written on paper does not always align with the lived realities of those who attended these schools. Context is essential—by reading between the lines, cross-referencing sources, and centring survivor testimonies, we can gain a more accurate picture of the injustices that took place.

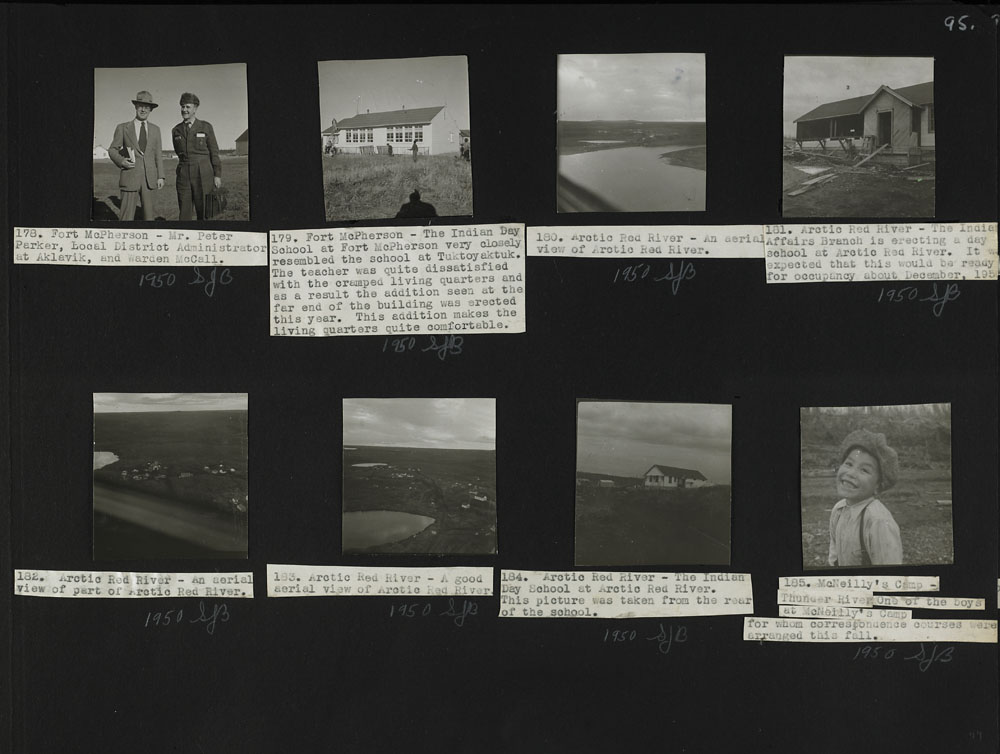

Photographs taken at Tetl’it Zheh (formerly known as Fort McPherson) and Tsiigehtchic (formerly known as Arctic Red River), and in the vicinity of Thunder River, Northwest Territories, the former Department of Indian Affairs, R216, RG85, volume 14980, album 37, page 95. (e010983667)

What’s in the Records

The records we work with come from government departments, school administrators, and other officials involved in the operation of the Day Schools system across Canada. These files provide a detailed picture of what these schools were like, who attended them, how they were run, and the challenges that students faced.

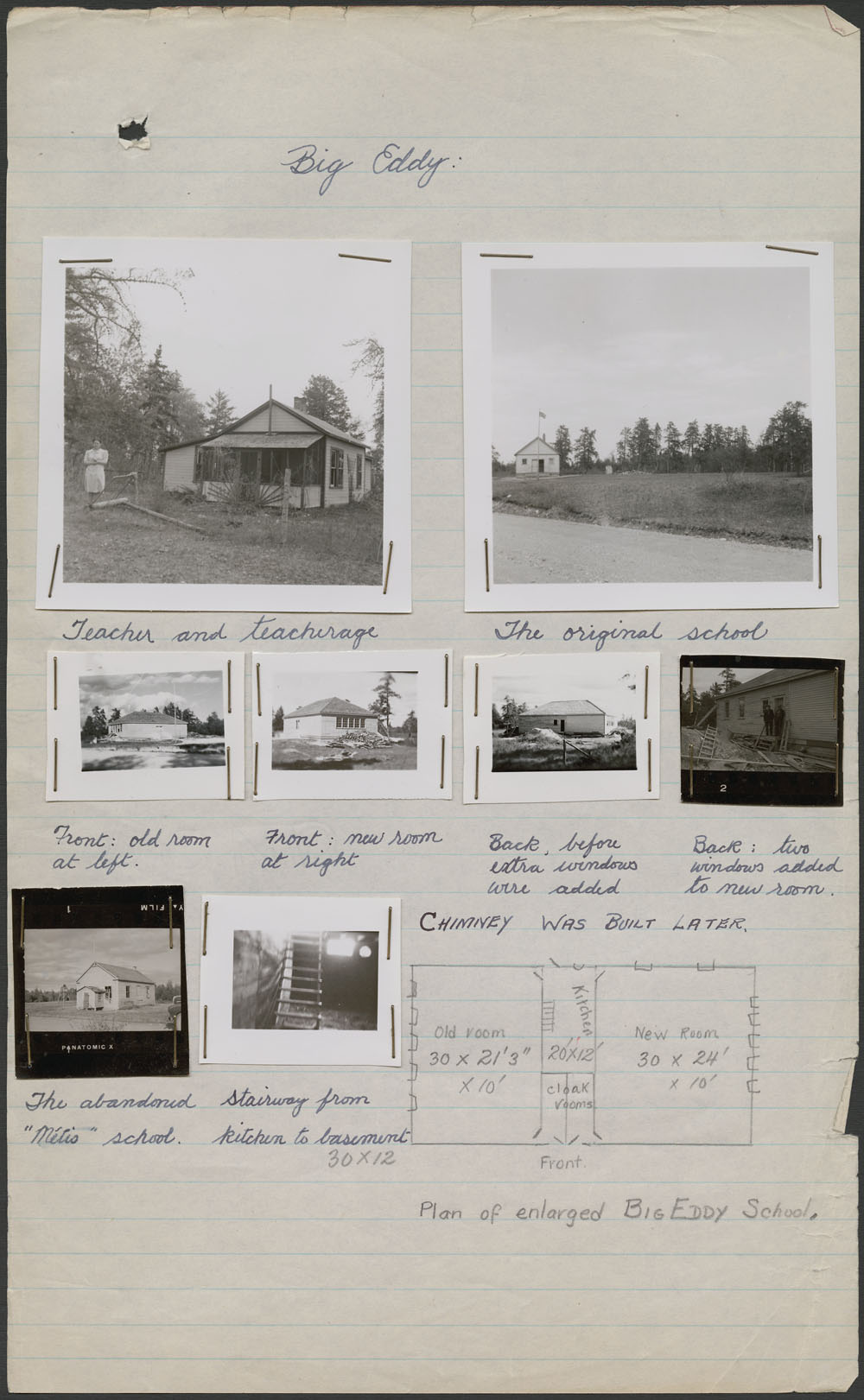

Big Eddy Day School, The Pas, Manitoba, ca. summer 1947, the former Department of Indian and Northern Affairs. (e011078102)

The documents left behind tell a complex story of daily life in these schools. Attendance reports and lesson plans provide glimpses into the classroom, while report cards reflect both student progress and the biases of the system. Medical reports and sanitation records reveal the often-poor conditions children endured, and financial ledgers expose how resources were allocated—or withheld—impacting the quality of education and care.

Letters and memos paint a picture of strained relationships between school staff, government officials, and families. Agreements between governments and school operators illustrate the shifting responsibilities and lack of accountability, while resignation letters hint at the high turnover of teachers. Maintenance reports document deteriorating buildings, and truancy records show how students were monitored and disciplined—often harshly.

Please keep in mind that individual student files might not contain all these types of records.

Together, these records provide crucial context for understanding the experiences of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Nation students at these schools, uncovering both the daily realities and the broader systemic injustices they faced.

How These Records Support Truth and Reconciliation

Understanding what happened in Day Schools is crucial to reconciliation. Survivors have shared their experiences, and historical records provide documented evidence that supports their truths. These files are essential for several reasons:

- Legal claims: Survivors who made claims under the Federal Indian Day Schools Settlement Agreement used these records to help verify their attendance at a specific school or provide supporting documentation for their experiences.

- Family history: Descendants of Day School students can use these records to learn more about their relatives’ education and experiences.

- Academic research: Scholars and historians studying the impact of these schools on Indigenous communities rely on these records to uncover policies, funding disparities, and systemic mistreatment.

- Public awareness: Making these records accessible ensures that Canada does not forget this painful chapter of its history and helps promote broader understanding and accountability.

If you’re researching Day Schools—whether for family history, legal claims, or academic work—these records can be invaluable. But archival research requires patience. Documents might be incomplete, handwritten notes can be hard to decipher, and government jargon is… well, let’s just say it’s not always user-friendly.

That’s where we come in. The Day Schools Project team at Library and Archives Canada is working hard to describe these files to make them more accessible. Due to privacy laws, we cannot include names of students or school staff in descriptions. However, when files do contain names, we add a note to inform researchers. The descriptions include names of schools, communities, the types of documents contained in the file, and whether there are photographs, drawings, maps, or plans. This information is fully searchable. Most importantly, we want researchers to understand what’s in these records and how to navigate them.

So, if you find yourself knee-deep in correspondence about school boiler repairs, don’t worry—you’re on the right track.

Additional Resources (Library and Archives Canada)

- Day Schools Project

- Day Schools Project: Research guide

- Indian Residential School records: Research guide

- We Are Here: Sharing Stories

- Federal Indian Day Schools: Education under the Indian Act—what did this mean for Métis Nation and Inuit children?

- Blog article about the Day Schools Project

External Resources

- Federal Indian Day Schools

- National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

- Official website of the Federal Indian Day School Class Action

- Schedule K: List of Federal Indian Day Schools (Microsoft Word—Document 3)

Marc St. Dennis worked as an archivist on the Day Schools Project at Library and Archives Canada from January 2024 to March 2025.

Marc, Excellent advice re navigating these important records… well done! Fred