By Ariane Gauthier

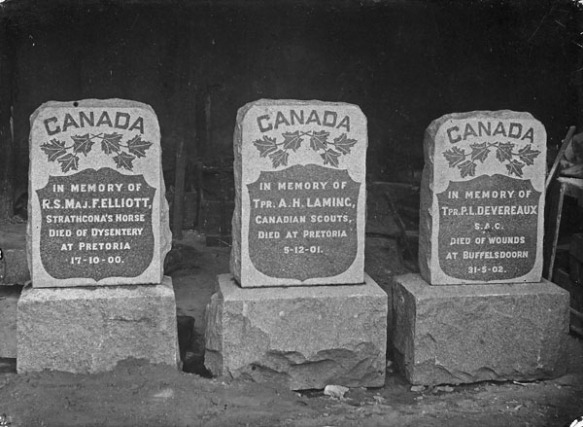

Many Canadian war graves and military cemeteries have been established around the world, as a result of the conflicts in which Canada has been involved since Confederation (1867), from the Boer War (1899–1902) in South Africa to the conflict in Afghanistan (2001–14).

The graves of soldiers Elliott, Laming and Devereaux, killed in the South African War (e006610211).

Colonel H.C. Osborne, war graves (e010679418_s1).

Canadian military cemetery at Bény-sur-Mer, France (e011176110).

Canadian cemetery in Agira, Sicily (e010786150).

Mrs. Renwick lays a wreath on behalf of Canadian mothers and wives on Remembrance Day in Japan (a133383).

Have you ever wondered why so many Canadian families allowed for the final resting place of their loved ones to be where they fell in combat?

Quite simply, because it was the only option—at least, initially.

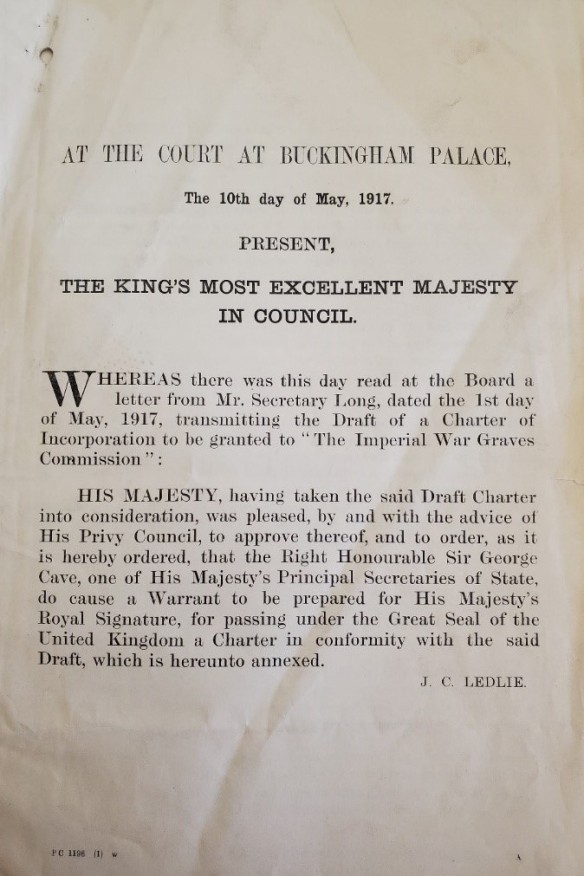

To understand, we must delve into the context of the First World War, the first mass industrial war. The technological and military advances of the modern era caused skyrocketing mortality rates. As a result, the British Empire had to manage the rapid recruitment of reinforcements in addition to the thousands of deaths in a war where the repatriation of bodies was practically impossible if not discouraged. It was dangerous to search for remains in active combat zones, and moving so many corpses could easily have led to worldwide epidemics. That said, the door remained open to changing the status quo once hostilities were over. On May 10, 1917, the Imperial War Graves Commission was created by Royal Charter, with a mandate to look into the issues of deceased soldiers and war cemeteries for the entire British Commonwealth.

War Office (United Kingdom) – Imperial War Graves Commission – Charter (MIKAN 1825922).

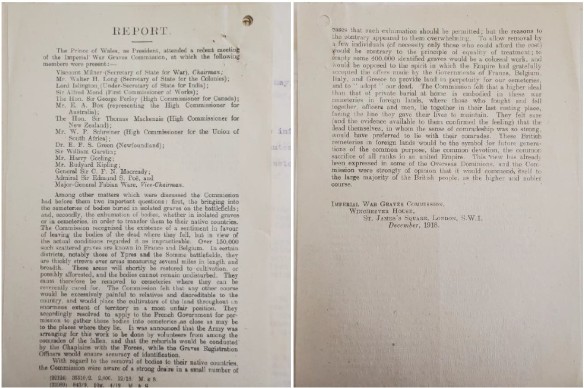

There was no consensus among families regarding the question of cemeteries being maintained in perpetuity. Lively debates about the war graves issue took place in many parliamentary institutions. Speakers appealed to the humanity and compassion of politicians, so that the families of fallen soldiers could bring home the bodies of their fathers, brothers, husbands or sons, and in some cases, their sisters and daughters. However, no petition could change the verdict issued by the Imperial War Graves Commission:

War Office (United Kingdom) – Imperial War Graves Commission – Refusal to permit removal of bodies from countries in which they are buried (MIKAN 1825922).

“To allow removal [of war dead] by a few individuals (of necessity only those who could afford the cost) would be contrary to the principle of equality of treatment; to empty some 400,000 identified graves would be a colossal work, and would be opposed to the spirit in which the Empire had gratefully accepted the offers made by the Governments of France, Belgium, Italy and Greece to provide land in perpetuity for our cemeteries and to “adopt” our dead. The Commission felt that a higher ideal than that of private burial at home is embodied in these war cemeteries in foreign lands, where those who fought and fell together, officers and men, lie together in their last resting place, facing the line they gave their lives to maintain. They felt sure (and the evidence available to them confirmed the feeling) that the dead themselves, in whom the sense of comradeship was so strong, would have preferred to lie with their comrades. These British cemeteries in foreign lands would be the symbol for future generations of the common purpose, the common devotion, the common sacrifice of all ranks in a united Empire. […]”

This decision ensured that Canadians who had died overseas during the First World War remained on those fields of honour. The cemeteries that were built in their memory can still be visited today; they are maintained by the Imperial War Graves Commission, now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. On July 15, 1970, Canada’s policy on the repatriation of soldiers who had died overseas changed. Order in Council P.C. 1967-1894 stated that the family of a soldier killed in action on or after that date could request his or her repatriation for a funeral. The loved ones of deceased service members can now have them brought home.

Additional resources

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission website

- Directorate of History and Heritage, National security and defence

- Online collection: sub-series Correspondence with Canadian and British Government Departments has the original documentation used for this blog post

Ariane Gauthier is a reference archivist in the Access and Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - November 18, 2023 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte