By Richard Yeomans

On August 4, 1914, Britain formally declared war on Germany, a decision that brought Canada into the theatre of conflict in Europe because of its status as a dominion within the British Empire. Though the Dominion Government could decide the extent of its involvement, Prime Minister Robert Borden declared in a speech to the House of Commons on August 19, 1914, that Canada would “stand shoulder to shoulder with Britain and the other dominions in this quarrel. And that duty we shall not fail to fulfill as the honour of Canada demands it. Not for love of battle, but for the cause of honour.” More than half a million Canadians enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) between 1914 and 1918, including volunteers and conscripts, while thousands more found ways to contribute to the war effort on the home front.

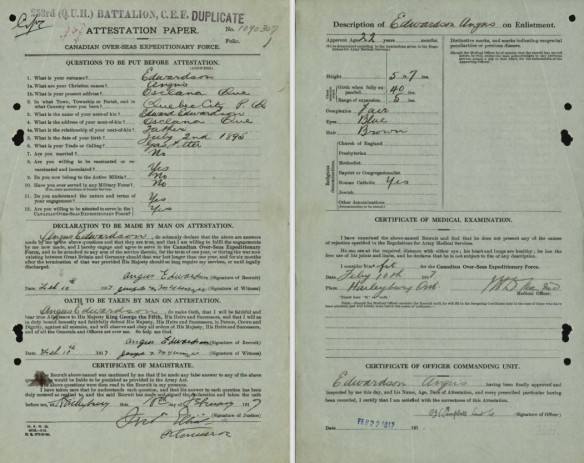

There are roughly 622 000 individual First World War service file records held by Library and Archives Canada (LAC), which document enlistment (attestation), movement between units, medical histories, pay and discharge or notification of death. These files are generally between 25 and 75 pages in length and are excellent sources for many different types of historical and genealogical research.

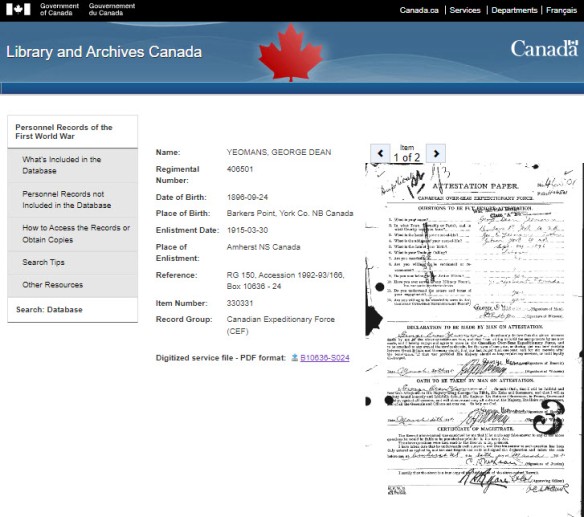

Original Personnel Records of the First World War database (Library and Archives Canada).

Access to the Personnel Records of the First World War database at LAC has been available for free online for nearly two decades via a standalone Personnel Records database. This database incorporated CEF files with Imperial Gratuities, Non-Permanent Active Militia, Rejected CEF Volunteers, and Royal Newfoundland Regiment and Forestry Corps records. Researchers familiar with this older database were able to search the archives by first and last names, regimental numbers, city or province of birth and/or enlistment and box number. Results were displayed in alphabetical order but could be reordered by date of birth, rank or regimental number.

Selecting an individual file from the results list provided a generic description of the record and included a digitized copy of the service file in PDF format that could be either opened and read or downloaded and saved to your computer. Every service file had a unique web URL, which historical researchers and genealogists alike could copy or save to easily access later.

Individual file view in the original Personnel Records of the First World War database (Library and Archives Canada).

For 10 years, this database provided Canadians at home and across the globe with access to a collection of records that document an important part of their family histories and connections to a shared national history. Library and Archives Canada is committed to maintaining and expanding that level of access as we continue to develop and improve upon our digital archival databases including Collection Search, Census Search and our new First World War Personnel Records database.

Launched in November 2023, this new database was developed as part of ongoing work to bring all of LAC’s standalone databases into one federated search tool, Collection Search. This work is necessary because the older web application that hosts the standalone CEF database is no longer sustainable to maintain. To keep these records accessible for years to come, these files were successfully migrated into Collection Search and a new database tool was created to streamline access to the Personnel Records of the First World War. This database tool offers all the same search features as the original application while also offering new ways to search, filter and extract records and data for research.

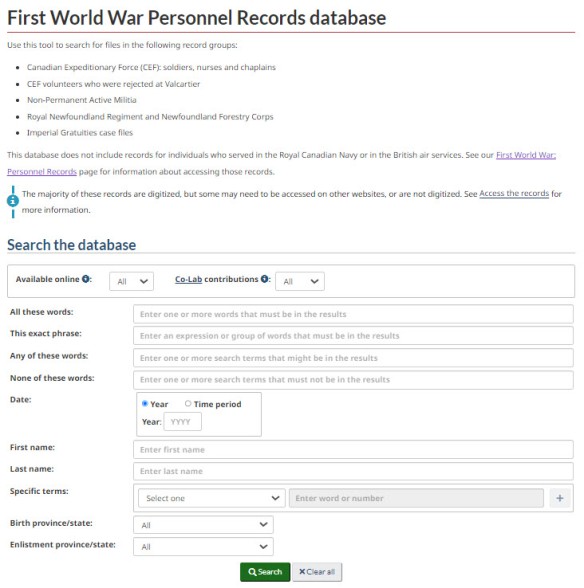

New First World War Personnel Records database (Library and Archives Canada).

Researchers may search the new database by using first and last names, regimental number, enlistment city and province, or by using specific terms including unit number and enlistment date.

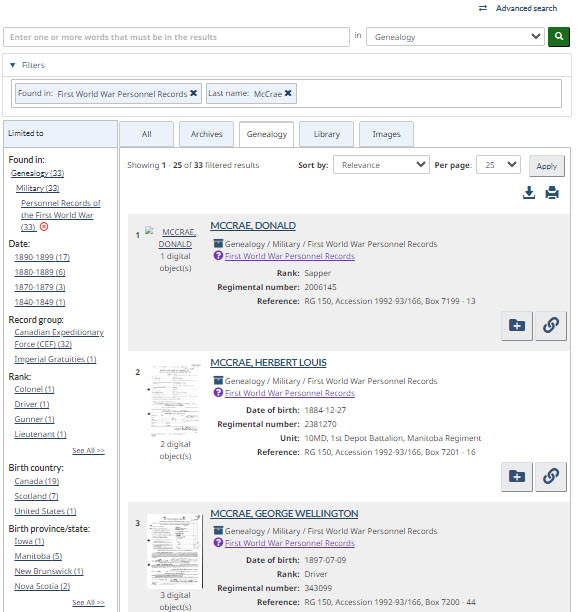

New features include the ability to search by date range, to save records of interest to your My Research using your LAC My Account and to apply filters during your search to help organize and limit the number of record results listed. It is important to note that both databases will provide you with the same number of search results based on similar search criteria. For example, searching the last name McCrae in either database will produce 33 different search results that you may select from. However, in the newer Personnel Records database, you can reduce the number of results using a variety of limiter options located on the search results page. These limiters include information such as military rank, date range for year of birth, birth country or different enlistment geographic options.

Search results for last name McCrae (Library and Archives Canada).

Applying these limiters will generate a reduced list of results that is more specific and refined according to the search parameters that you control. Because you control the search criteria, it is possible to perform both extremely specific and very general searches using the new Personnel Records database.

Finding Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae

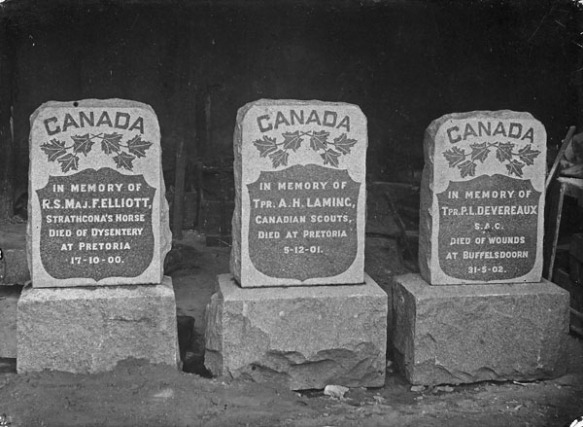

Accessing attestation papers and personnel records available online, for free, through LAC remains an important staple within our digitized archival catalogue. For example, researchers can access digitized archival records using the personnel records of Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae, the Canadian physician and poet best known for authoring the war memorial poem “In Flanders Fields.”

Lieutenant-Colonel McCrae’s records may be found in several different ways, including searching by his first and last name, unit number, city of enlistment, or regimental number. Even just a name is a good starting point. Searching the last name McCrae yields 33 results in both the old and the new database, while searching for John McCrae generates 4 results.

Search results for John McCrae in either database (Library and Archives Canada).

From the list of results, displayed above in both the old and new CEF databases, researchers can also view a general abstract about the file that includes (if available) regimental numbers, date of birth and archival reference information. In the older CEF database, this information could also be used to reorganize the list view of records. In the new database, it is still possible to reorganize results by date of birth or alphabetically, but unlike in the older database, you can reduce the number of results in the list view using the filters available. In this instance, we know that the John McCrae who penned “In Flanders Fields” was born in Guelph, Ontario, and we can select that option located under “Birth City” on the left-hand side of the results list. Doing so will generate a new list, now filtered to only one result that we can open and view.

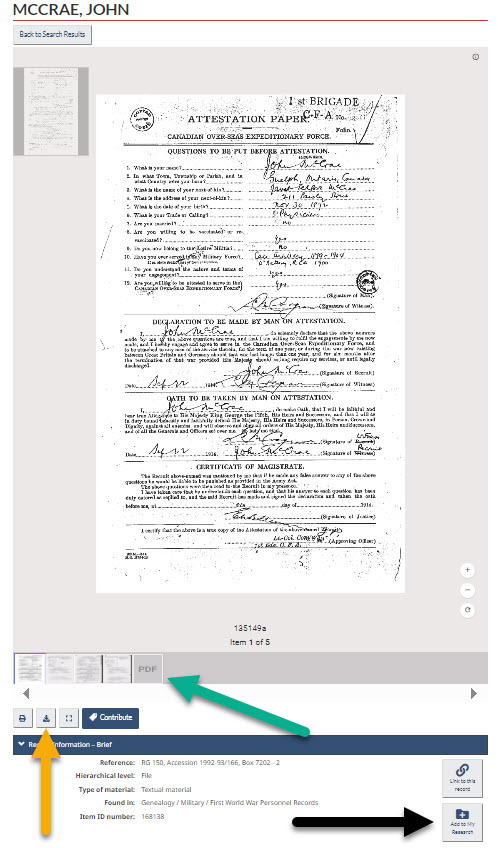

Viewing the personnel record of John McCrae (Library and Archives Canada).

Opening a record in the new CEF database looks different but still retains the functionality of the original database. The first page of the attestation paper will display, by default, on the screen as shown in the image above.

Green Arrow: In the image carousel below the attestation page, you can navigate between the pages of that record. At the end of the image carousel is a PDF icon. Selecting the icon will load a scan of the entire personnel file, which includes a copy of the attestation paper. This file may be downloaded, for free, as it was in the original database.

Black Arrow: If you have a LAC My Account, you can save records of interest to a research list. Clicking the “Add to My Research” button while signed into your LAC My Account will generate a list of your current save folders that you may select and add to, or you may create a new folder and add the record. Previously, researchers had to copy and save internet URLs to quickly access the records they viewed. Using the My Research feature of LAC’s My Account, you may now build entire research lists with records held at LAC, like a bibliography.

Yellow Arrow: To download the file in its entirety, simply click the download button, check that you agree to our copyright terms and conditions and select “Download file.” The record will then be downloaded to your computer or electronic device in PDF format.

Behind the scenes: Digital Access Services

Maintaining consistent and sustainable online access to the records that document the Canadian experience during the First World War presents many challenges. Building a database tool that can serve not only historians and genealogists but also individuals with limited experience using online archives is a balancing act. Creating a tool that can meet the needs of many kinds of researchers begins by asking how researchers experience LAC online and what products we can develop or adjust to improve that overall experience. Improvements to our digital products, such as the new First World War Personnel Records database, are ongoing and responsive to the feedback that we receive from users. If you wish to submit feedback about how we can improve the new First World War Personnel Records database or other digital products currently offered by LAC, please consider emailing your suggestions to the Digital Access Services team or scheduling a feedback session with our UX Designers. LAC’s Digital Access Services team is committed to preserving access to digitized military personnel files and recognizes the significance of these documents to researchers here in Canada and around the world.

The Digital Access Services team is comprised of User Experience Designers, Data Scientists, Web Programmers and Product Managers. The members of our team are also experienced genealogists, historians, historical researchers, archivists, and client-focused public servants who are likewise stakeholders in the preservation and promotion of Canada’s history and heritage. Maintaining free and public access to the roughly 622 000 individual First World War service files in addition to millions of census records, immigration and citizenship records, government publications such as the Canada Gazette, audio files, images, and so much more is a huge job. It is a task that requires time, patience, and more than a little bit of teamwork. Nevertheless, our work continues, and the Digital Access Services team looks forward to bringing new research tools and updates in 2024.

FAQ about Library and Archives Canada’s CEF records and databases

Why is the older First World War Personnel Files Database being decommissioned?

The original database is fast approaching being 10 years old. The platform that hosted the database, Microsoft SharePoint, was first released in 2001 and is becoming more obsolete as time goes on. This means that it will become more difficult for our Web Designers and Programmers to maintain the original database and we risk losing access to the military personnel records altogether. Library and Archives Canada’s Digital Access Services team has been proactive and began migrating records into Collection Search in 2019. This way we can preserve free and public access to these and other records for years to come.

Who oversees the new First World War Personnel Records database?

The Digital Access Services team at LAC is responsible for the maintenance of LAC’s online databases, including Collection and Census Search. Our team does not alter or edit archival documents. Rather, our work focuses on access to the digitized copies of records.

Is the First World War Personnel Records database distinct and separate from Collection Search?

Yes and no – the new database pulls records that have been migrated into Collection Search, which is LAC’s federated archival catalogue search tool. Digital Access Services continues to migrate records from other older standalone databases into Collection Search, while also acknowledging that many users have more specific research needs. Using database filters, or by creating search forms such as the new First World War Personnel Records database, we can streamline access to specific groups of records as if the standalone databases still exist within Collection Search.

Will internet URLs to the older database stop working?

No – using URL redirects, saved internet links to specific files will redirect users to the location of that specific record within Collection Search. This means that if you have a collection of saved links to the location of specific military service files in the older application, you can still use those links to locate those records in the new application.

Am I still able to save and download service files?

Yes – the option to download PDF formatted copies of attestation and personnel files is available. Users with a LAC My Account may also save records to their My Research and create entire lists of service records that can be retained without the need to saving an internet URL link.

Richard Yeomans is the Quality Assurance Officer on the Digital Access Team – Access and Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=584&h=159)

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=584)