This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

By Masha Davidovic

The Indian Claims Commission of the 1970s came into existence with a bang, as a footnote to Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s government’s proposed 1969 White Paper (formally known as the Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy). The White Paper was truly explosive, an assimilative document laying out the government’s intention to abolish Indian status, the Indian Act, and the reserve system. It set off a storm of resistance and activist mobilization from coast to coast to coast. Suddenly, First Nations communities across the country faced an open threat that did not discern or discriminate, but that simply said: we will assimilate everyone at once into the Canadian body politic, there will be no more special treatment, no more Indian department, and no more “Indian problem.”

The swell of pan-Indigenous organization in response became a tidal wave that swept the White Paper aside—it was abashedly retracted in 1970—and kept on moving, as Inuit and the Métis Nation joined their voices with those of First Nations. We are still feeling the effects today: these were the years that saw the Calder case’s landmark recognition of ongoing Indigenous title and the founding of provincial and national Indigenous organizations, including the precursors to today’s Assembly of First Nations (AFN), Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), and Métis National Council (MNC). These years were marked by resistance and, sometimes, open antagonism, the crescendo of simmering pushback against government policy and conduct.

A memo from Andrew Rickard, President of Grand Council Treaty #9 (today’s Nishnawbe Aski Nation), March 12, 1973. Library and Archives Canada, page 3. (e011267219)

Yet the Indian Claims Commission, essentially a procedural footnote intended to tie up loose ends and bring to an end the era of Indigenous claims, might be called the most enduring legacy of the original 1969 Statement. The newly digitized primary materials of the Commission tell the story of the tumultuous 1970s, but also that of the Commission’s surprising success. Adapting to a shifting political context, it took on the role of mediator between the Crown and Indigenous communities and ultimately did much to lay the groundwork for contemporary claims processes in Canada.

The Collection

The Commission was, for the most part, a one-man office.

Biography and picture of Dr. Lloyd I. Barber, from a keynote presentation at a conference. Library and Archives Canada, page 77 (e011267331)

By the time the Regina-born, Saskatoon-based academic Dr. Lloyd I. Barber began his duties as Indian Claims Commissioner, his terms of reference had changed. Rather than adjudicating and closing off claims, he was researching histories, assessing grievances, and building contacts and relationships. He corresponded constantly with Ottawa, as well as with a veritable who’s who of Indigenous leaders. In many of these letters, it is clear that he saw damage control as a large part of his job. His relative independence from Ottawa allowed him leeway to echo Indigenous communities’ calls for justice and equity, a role he played without hesitation.

Letter from Commissioner Lloyd I. Barber to Judd Buchanan, Deputy Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, concerning hunting, fishing, and trapping rights of prairie First Nations. Library and Archives Canada, page 35 (e011267232)

A veteran professor of commerce, Barber established a consistent tone across his letters—patient, calm, reassuring, and often quite apologetic. He embodies a sensitive and sympathetic figure, defining his plain language carefully against that of bureaucrats and civil servants. This persona is stamped on the materials of the fonds and cannot be easily separated from the successes of the Commission as a whole.

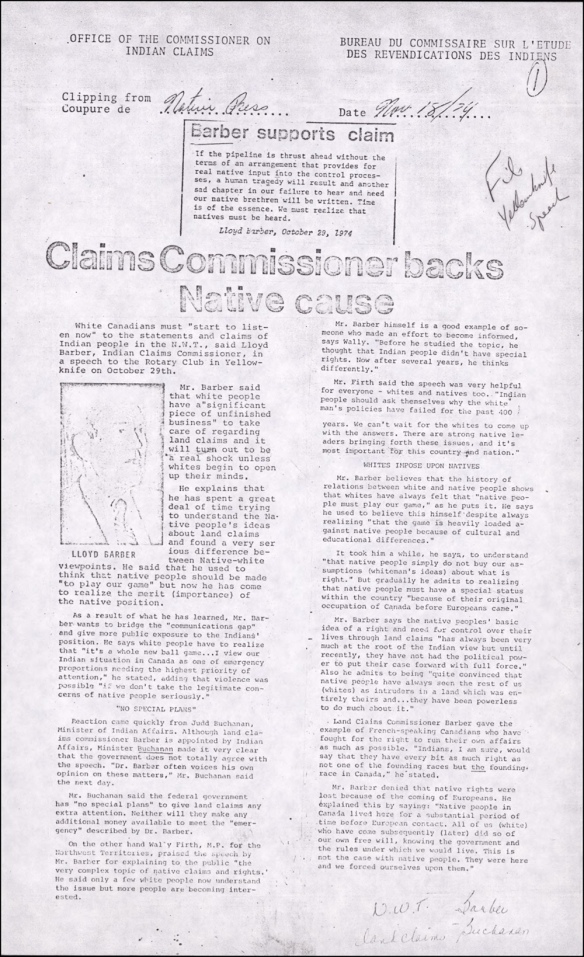

Newspaper clipping from Native Press, November 18, 1974, pertaining to a speech given by Lloyd Barber in Yellowknife. Library and Archives Canada, page 59 (e011267332)

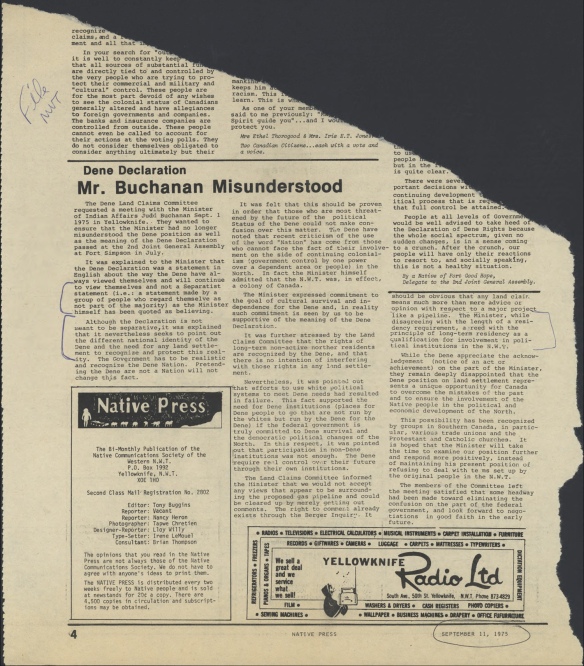

The true litmus test for the Commission’s successes consisted in the dialogues Barber established, and here the research and reference materials assembled by the Commission are revealing. The Commission collected a wide swath of material, organized by province, band, and claim—from historical records from the early nineteenth century onward, to transcripts of parliamentary debates, to endless clippings from newspapers, many of them from local First Nations papers. These clippings offer snapshots and summaries of issues on the ground between Indigenous and non-Indigenous society in the heated 1970s. They also reflect the Commission’s function in assessing not just the policy and logistics of land claims, but the public perception of these issues, particularly in First Nations communities. These media sources provide a rich backdrop in understanding both the Commission’s general recommendations and its concrete interventions in specific grievance processes.

Newspaper clipping pertaining to the 1975 Dene Declaration. Library and Archives Canada, page 21 (e011267159)

In 1977, the Indian Claims Commission turned in a compelling report summarizing its findings and recommendations. It was superseded by the Canadian Indian Rights Commission, which continued the work and built on the relationships Barber had initiated. Born in struggle and contradiction, Barber’s Commission had managed to not only walk the wobbly tightrope between government and Indigenous communities, but had actually succeeded in rerouting much of the swell of activism of the 1970s back into channels of dialogue and negotiation. It remains a decisive factor in a decisive period in Crown-Indigenous relations.

This blog is part of a series related to the Indigenous Documentary Heritage Initiatives. Learn how Library and Archives Canada (LAC) increases access to First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation collections and supports communities in the preservation of Indigenous language recordings.

Masha Davidovic is an archival assistant on We are Here: Sharing Stories, the Indigenous digitization initiative, in the Public Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=584)

Nice..

Greetings. How can I communicate with Marko Davidovic, the author of today’s LAC blog?

If that is not possible, can you answer the two questions I have? Are these digitalized documents on line? If not, how are they available on microfilm?

Thanks.

Best regards,

Rarihokwats

Hi there, this collection has been digitized and described in our database, and the digital PDFs have been linked to the corresponding records. This is the link to the fonds via Collection Search Beta, and the individual PDFs can be navigated to through “View lower level descriptions”: http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=143&new=-8586472068942809947. Good luck in your search!

Reblogged this on seachranaidhe1.