By Melissa Beckett and François Deslauriers

By Melissa Beckett and François Deslauriers

A glimpse into the microfilm room

In a dimly lit room, two imaging specialists sit in opposite corners. Each stares at their screen, where a series of images is constantly flowing from one side to the other. The rhythmic mechanical sounds of the microfilm scanners are occasionally interrupted by the high-pitched whine of the rewind, and a clunk as the last of the film winds back around its reel. With white-gloved hands, a specialist removes the reel from her scanner and places it back into its round metallic canister, which she returns to its archival box. She removes the next canister and slices around the taped edge with a pocket knife. She takes out the reel and mounts it on the scanner, winding the film around a series of rollers and then onto another plastic reel.

Meanwhile, the other specialist has stopped the process on his scanner. He needs to readjust some settings because the images in this section of the reel are much brighter than the earlier ones. He adjusts the exposure values in the software until he is satisfied with the appearance of the images in the preview window. The specialist scans a short section of film and opens it in the auditing software to double-check. He views one of the documents at full size, examining it closely. He then rewinds the film to the beginning, starting the scanning process all over again.

The project

For the Census 1931 project, the Digitization Services team digitized 187 microfilm reels, for a total of 234,678 images. At this time, by law, the reels were still subject to statistical secrecy, and a security procedure/protocol had to be followed. Only “deemed employees” who had taken the Statistics Canada Oath or Affirmation of Office and Secrecy were authorized to view the material. Reels were kept locked in a secure room, and all digitization was performed completely off-line.

The Census 1931 microfilm reels contain about 1200 images of census documents on each reel of 35-mm black-and-white polyester film. The imaging specialist digitizes from the print master, a copy of the archival master reel, in order to prevent any deterioration of the original.

Microfilm is an effective means of preserving information for long periods of time (reels can last for 500 years). Microfilm stores vast quantities of information in a small amount of space and supports preservation of the documents contained by removing the necessity of handling them. Digitizing microfilm reels provides another level of preservation as well as of accessibility to the public, who are then able to view the images from anywhere with an Internet connection.

The scanning process

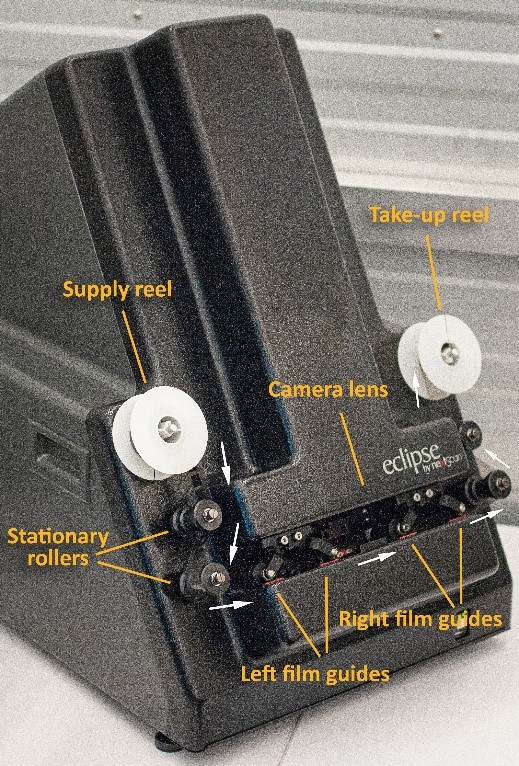

The Eclipse Rollfilm scanner by nextScan, with main components labelled. Credit: François Deslauriers

For this project, the digitization of the 1931 Census was performed with the use of the Eclipse Rollfilm scanner by nextScan, a dedicated microfilm scanner designed to digitize both 16-mm and 35-mm reels, in conjunction with an off-network computer. Film is threaded from the supply reel past stationary rollers and film guides to a take-up reel. The pinch rollers lower to hold the film in place on the film guides, automatically adjusting the tension of the film. The film is guided past a macro lens and digital sensor above, while lit from below through the film emulsion by a strip of red light. The reel is digitized as one long, uncompressed, grey-scale image file, referred to as a ribbon.

The imaging specialist handles the film using cotton gloves, being careful to touch the edges only. With the NextStarPLUS® Capture software, the reduction ratio (which is noted on the film and allows images to be reproduced at a 1:1 ratio) must be set, in addition to the resolution, film type (16-mm or 35-mm) and polarity (negative or positive). Before scanning, the specialist must also ensure that the exposure of the images is correct and that the lens is focused so the image is sharp.

With a live view on the screen, the specialist makes adjustments to the exposure and the focus. The specialist may zoom in on a focusing chart, as well as on the manufacturer’s information, printed along the edge of the film at regular intervals. The appearance of scratches or dust on the film can also be useful for determining sharpness. While the documents can be used to focus, this is only reliable if they were originally photographed with perfect sharpness.

A preview window during scanning allows the specialist to see when it is necessary to readjust settings over the course of scanning. When the documents were initially photographed, there may have been changes in lighting and exposure settings over the course of the reel. This results in some images appearing brighter or darker. The goal in digitizing each reel is to ensure that most of the documents will be legible, since adjustments in tonal values can only be made for the entire length of the film and not for each individual document.

After scanning is complete, the specialist rewinds the film and returns the reel to its canister.

The auditing process

After scanning the reels, the imaging specialist uses the NextStarPLUS® Auditor software to process the ribbons (the long image files associated with each reel). The software is used to detect and select each individual document within the ribbon so that they can be exported as separate image files. According to its detection settings, the software generates coloured rectangles around the documents. The specialist scrolls past rows of documents to select those that were not detected by the software and to adjust any rectangles that do not contain the whole document. On a second scroll through, a blackout setting changes the contents of the rectangles to black. This leaves any unselected white parts visible, making it easier to spot anything that may have been missed on the first pass, for additional quality control.

Each digitized document in the census is assigned an e-number, a unique identifying number used in this project to sort the images by place.

The images were initially exported as 10-megabyte TIFF files. TIFF is a “lossless” file format, meaning that there is no image compression. For the purposes of the project, JPEG derivatives (a “lossy” file format that requires less storage space and is more accessible) were created to aid in matching the digitized images to the census geographic districts and sub-districts, as well as for external partners working in artificial intelligence (AI). Information Technology created a script to efficiently turn the TIFF files into JPEGs.

Yesterday and tomorrow

Working in digitization at Library and Archives Canada means constantly improving processes and exploring new techniques and technology, to create the best-quality images possible. The 1931 Census was no different. As imaging specialists, we have been glad to play a small part in keeping Canada’s history alive and making it accessible to the public.

Melissa Beckett is an acting Imaging Specialist in the Digitization Services Division at Library and Archives Canada.

François Deslauriers is an acting Manager of Reprography in the Digitization Services Division at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=584)