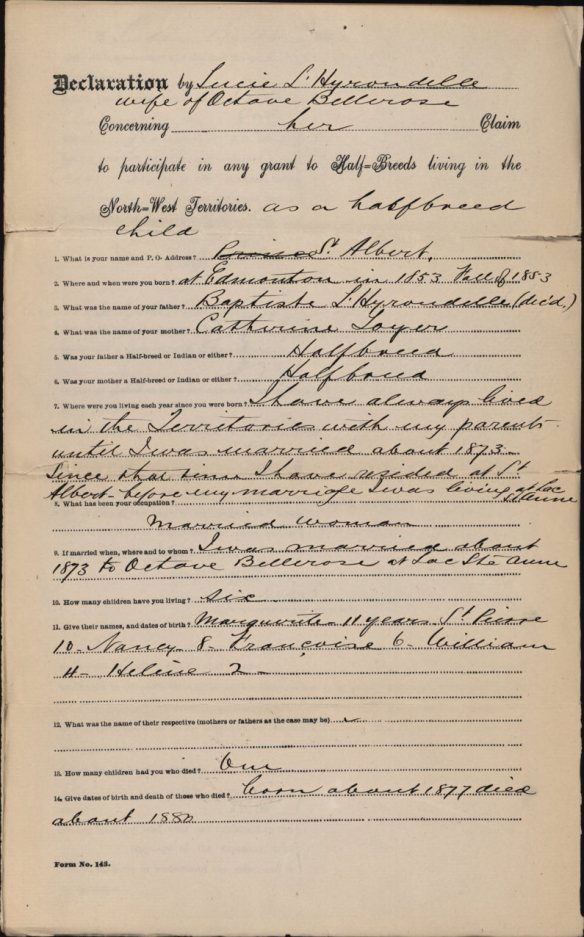

This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

Understanding the First World War from the perspective of the Indigenous Peoples of this land has been of paramount importance for many Indigenous researchers, such as myself. Dedicating hours upon hours to research a single Great War veteran is sometimes required just to identify that they were indeed Indigenous. While we have excellent resources about some of the very well-known First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation service members from that war, there is still much to discover in this realm of historical knowledge.

This post is not meant to convey the story of the Indigenous people who served during the First World War, nor would I attempt to simply generalize the experiences of Indigenous peoples into a single blog post. Instead, I will share the stories of two very different individuals and relate how research techniques can be used to better research an Indigenous person who served in the Great War.

The story of John Shiwak

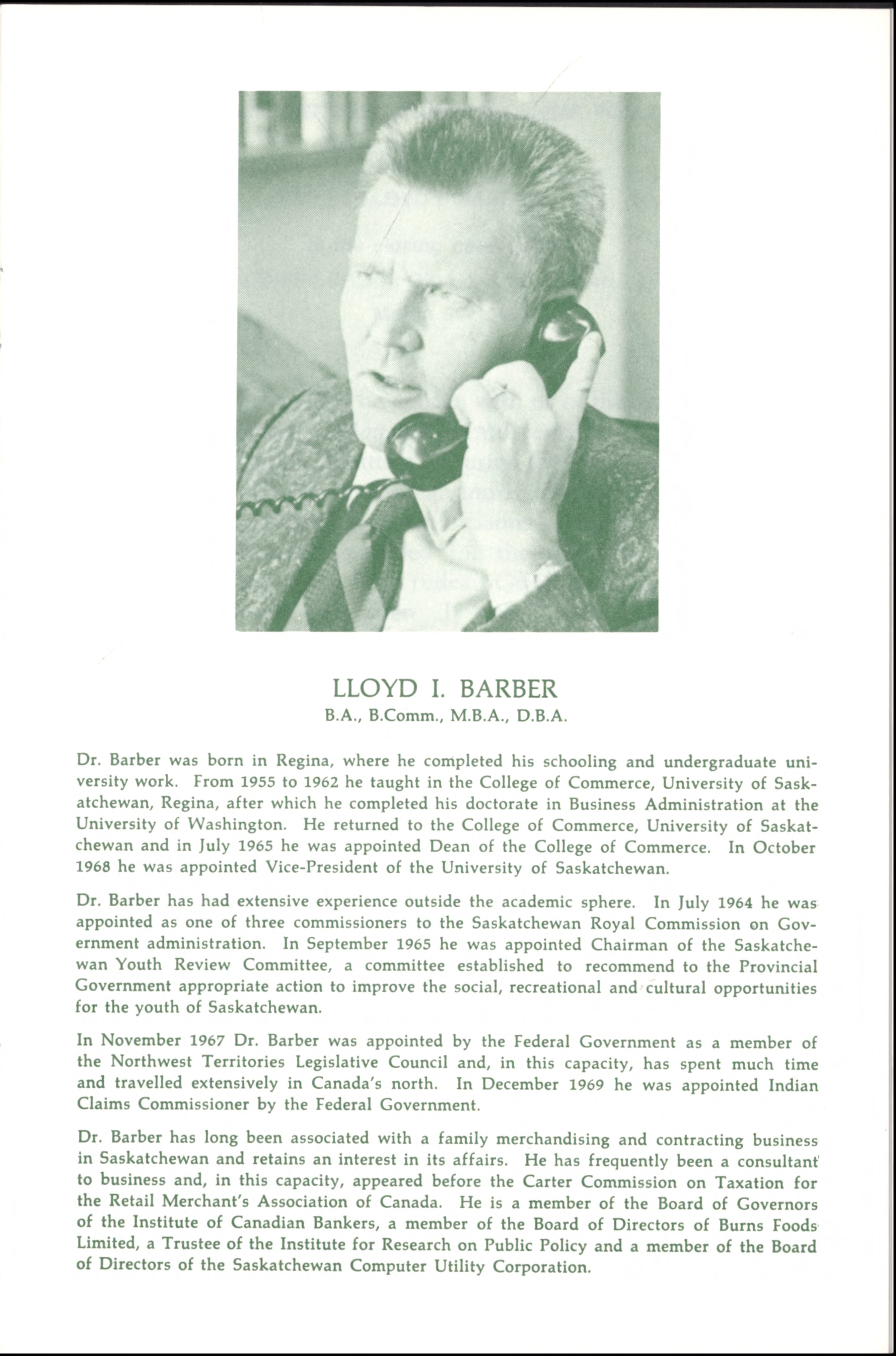

John Shiwak, Royal Newfoundland Regiment # 1735. The Rooms, Item E 29-45.

John Shiwak was born in 1889 in Rigolet, Labrador. A member of an Inuit community, he was an experienced hunter and trapper when he enlisted with the First (later “Royal”) Newfoundland Regiment on July 24, 1915. He was still in training when the regiment was sent over the top of the St. John’s Road trench at Beaumont-Hamel on July 1, 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. When Shiwak joined the regiment in France a few weeks later, on July 24, he was one of many who saw the aftermath of the near destruction of the regiment in the 45 minutes that they fought on the Somme battlefield. In April 1917, Shiwak was promoted to lance corporal. Unfortunately, that November, less than a year before the guns fell silent, Lance Corporal John Shiwak met a sad end. In the middle of the battle for Masnières (during the larger First Battle of Cambrai), Shiwak’s unit was struck by a shell, killing him and six others.

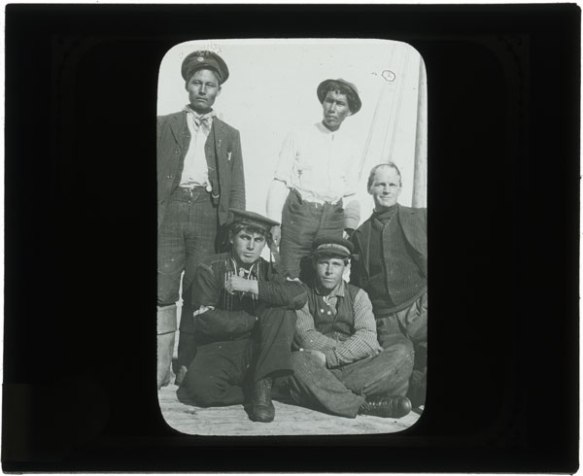

Members of the Legion of Frontiersmen (before 1915); John Shiwak is standing at the left. The Rooms, Item IGA 10-25.

This story is not uncommon in accounts of the First World War. The Inuk man was killed in the line of duty, in the midst of his brothers in arms. Yet his story is even sadder: until now, the gravesite of Shiwak and those six other brave men were never located. It is theorized that a school was built above the grave, the construction happening without the knowledge that seven soldiers of the Great War were buried there. Nevertheless, as with all casualties without a known resting place, Shiwak is commemorated. His name is forever etched on the bronze plaques at the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial in France, and at a similar memorial in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador.

The story of Angus Edwardson

The story of Private Angus Edwardson is of personal interest to me. He was my great-great-grandfather and fought at Passchendaele. He was born in 1894 in the northern, primarily Algonquin Anishinaabe, community of Lac-Barrière, about 300 kilometres northwest of Ottawa. On his enlistment form, Edwardson stated that he and his family resided in Oskélanéo, Quebec. For a very long time, our family did not know that he was Indigenous, nor did we know about his time in the trenches in any detail.

Luckily, in my line of work, one can discover some very interesting pieces of information. During a search through the 1921 Census, I found information that he was an “ancien soldat” (veteran); I was therefore able to find his attestation papers. While Edwardson’s story is much less noteworthy than that of Shiwak, his story provides an insight into the challenges of researching Indigenous men who fought in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) and indeed in the British forces as a whole.

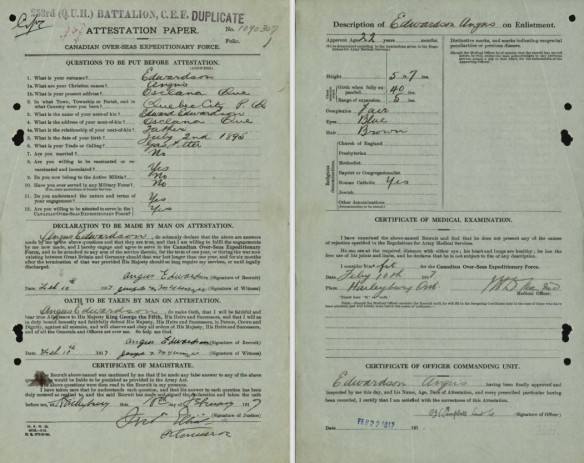

Attestation papers of Angus Edwardson (regimental number 1090307).

In the physical description of Edwardson, the enlistment officer wrote that his complexion was “fair,” his eyes “blue,” and his hair “dark.” This description does not reflect the racial idea of an Indigenous person, nor did the enlistment officer note that Edwardson was First Nations by writing the commonly used term “Indian” under the section of the form entitled “Distinctive marks, and marks indicating congenital peculiarities or previous disease.”

From what we can see in his records, Edwardson was a member of the 253rd (Queens’ University) Highland Battalion, though he served with a number of other battalions and regiments during his time on the front. Notably, while serving with the 213th Battalion on August 28, 1918, he was wounded in the left hand by a bullet.

Challenges facing researchers

As I mentioned, not knowing that a member of the CEF was Indigenous is a major sticking point for researchers. The attestation files may not contain this information at all. In fact, this is very common in the later years of the First World War. Neither of the two men that I have written about have the telltale designation “Indian” on their attestation forms. The only way we can know for certain that these two men were indeed Indigenous is by relying on additional sources.

The first of such sources is the often-overlooked census records. The census provides vital information about research subjects, and individual information can greatly increase success in researching Indigenous members of the CEF and the Royal Newfoundland Regiment (RNR). In the case of Edwardson, I discovered that he was in fact Indigenous by looking at his record in the 1921 Census. For Shiwak, there was an entirely different route to finding his identity, which was incredibly difficult. I uncovered information about Shiwak’s ethnic heritage through the memoirs of Sydney Frost, a captain with the RNR, entitled A Blue Puttee at War. This memoir, however, is not the only way to find out that Shiwak was Indigenous.

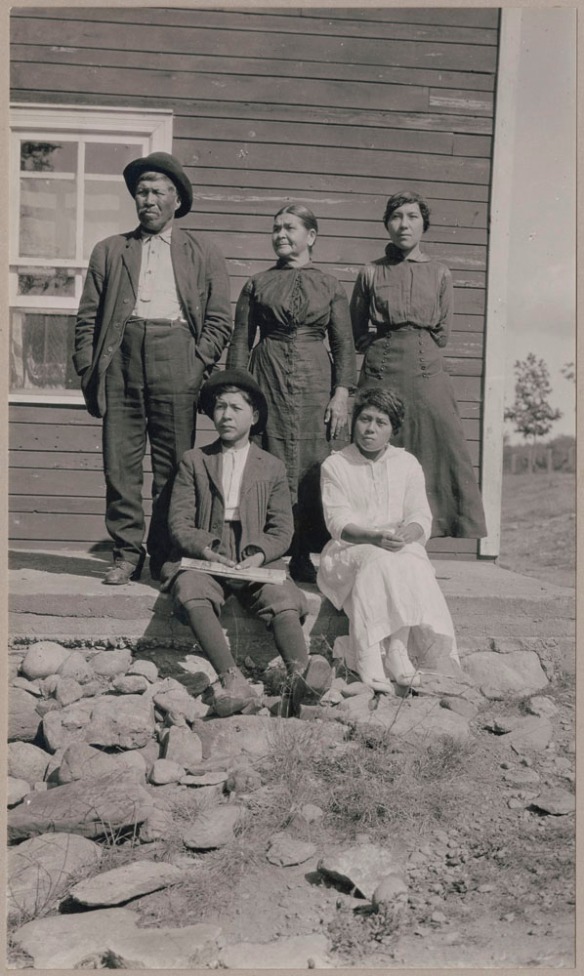

Census entry for Angus Edwardson and family, 1921 (e003065155).

Secondary sources about the First World War are numerous. For Shiwak, several appear when simply searching his name, but for other, lesser-known Indigenous members of the CEF, this may be more difficult. The excellent book For King and Kanata: Canadian Indians and the First World War by Timothy Winegard shows how we may be able to improve search techniques for Indigenous individuals and groups that served in the CEF. Though not explicitly, Winegard indicates the role of individual communities and their part in deciding to send men to enlist for the war effort. That said, this effort can be difficult, and it is worth reaching out to local genealogical societies and/or Indigenous communities for help in locating a list of names or simply an idea of how many men served from that community.

The final source of information that is quite useful in these cases is the so-called Indian Registers. These are archival documents with lists of names of members of bands. While the registers are a great resource for those researching members of a specific First Nations band and who are able to visit Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa, there are challenges remaining for those who do not know the band of their research subject or whether their subject died during the war. For individuals researching an Inuk or a member of a Métis Nation community, the challenges deepen, as there is very little primary source material from the period immediately after the Great War. It may be possible to identify Inuit or Métis Nation members of the CEF or RNR through secondary sources, but this can be challenging and take time.

Conclusion

Lance Corporal John Shiwak and Private Angus Edwardson both fought during the First World War. The former was Inuk and the latter was First Nations. The two cases exemplify the many challenges that face researchers when they are looking to find information about members of the CEF or RNR who were Indigenous. These challenges are multi-faceted, and they can pose significant difficulties in research into the stories of Indigenous veterans who fought in the Great War. There are some solutions and resources, including consulting archival records (census records specifically), checking with local Indigenous communities, and accessing some resources specific to Indigenous Peoples at Library and Archives Canada. Nevertheless, these proposed solutions can only go so far in helping researchers find information about Indigenous people who served in the First World War.

Additional resources

- Inuit soldiers of the First World War: Lance Corporal John Shiwak by Heather Campbell, Library and Archives Canada Blog

Ethan M. Coudenys is a Genealogy Consultant at Library and Archives Canada. They are proudly of Innu heritage and the descendant of a residential school survivor.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=584&h=159)

![On the left, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] is in his traditional First Nation regalia on a horse. In the centre, Iggi and a girl engage in a “kunik,” a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide, holds a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2022/09/image-1.jpg?w=584&h=365)

![On the left, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] is in his traditional First Nation regalia on a horse. In the centre, Iggi and a girl engage in a “kunik,” a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide, holds a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2022/09/image-1.jpg)

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=519)

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg)