By Gabrielle Nishiguchi

The DigiLab has hosted many projects since its launch in 2017, two of which were carried out by Landscapes of Injustice. Landscapes of Injustice is a major, seven-year humanities and social justice project led by the University of Victoria, joined to date by fifteen cultural, academic and federal partners, including Library and Archives Canada. The purpose of this project is to research and make known the history of the dispossession—the forced sale of Japanese-Canadian-owned property made legal by Order in Council 1943-0469 (19 January 1943) during the Second World War.

In total, over 40,000 pages of textual material and over 180 photographs were digitized by the two researchers with Landscapes of Injustice. Some of the documents are now available online for all to consult, including photographs relating to the internment of Japanese Canadians.

Photographs relating to Japanese Canadian internment

These photographs are from three albums of photographs taken during inspection tours of Japanese Canadian internment camps in 1943 and 1945. The first two albums contain images of camps in the interior of British Columbia taken by Jack Long of the National Film Board of Canada Still Photography Division.

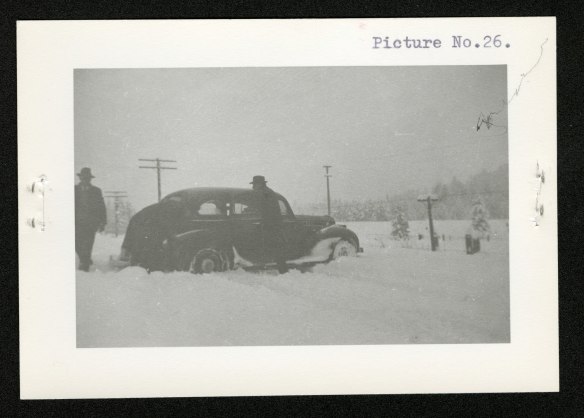

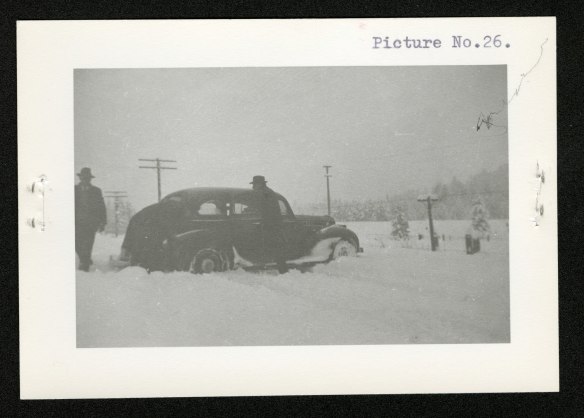

The third album contains twenty-seven images taken by Ernest L. Maag, International Committee of the Red Cross Delegate in Canada, in 1943. Among the Maag images are photographs illustrating the winter hardship of Japanese Canadian internment life. One photograph shows the International Red Cross delegate stuck in a heavy snowdrift during his 1943 camp inspection tour.

Another image shows snow shovelled against the shiplap walls of the internment shacks. There is tar paper on the outer walls for protection against the elements.

Picture No. 26 [The International Red Cross delegate stuck in a heavy snowdrift during his 1943 camp inspection tour] Credit: Ernest L. Maag (e999900382-u)

Picture No. 5 [Snow shovelled against the shiplap walls of internment shacks. Notice the tar paper on the outer walls of the shacks for protection against the elements. Credit: Ernest L. Maag] (e999900386-u)

All photographs digitized during the project are available in

Collection Search under the key words “

Photographs relating to Japanese-Canadian internment.”

A defective and prejudicial logic

It should be noted that the Long photographs were commissioned by the Canadian government during the Second World War to create the false impression that some 20,000 Japanese Canadians, whom it had forcibly interned in 1942, were being especially well treated and were, in fact, enjoying their lives in internment camps.

Bureaucrats employed the defective and prejudicial logic that there was an equivalence between Canadians of Japanese ethnic origin—75% of whom were Canadian citizens by birth or naturalization—and ethnic Japanese in Imperial Japan. The rationale behind this discriminatory belief was that, if these photographs were seen by the Government of Japan, they might secure favourable treatment for Canadian soldiers held captive by the Axis Japanese.

Original captions

The original captions reflect the purpose of the photographs and were a product of 1940s thinking. Internees are not referred to as Canadians. They are all “Japanese” or, in one offensive case, “Japs.” Non-Japanese are “whites,” “Occidentals” or “other racial groups.” The names added to the captions are for non-Japanese persons.

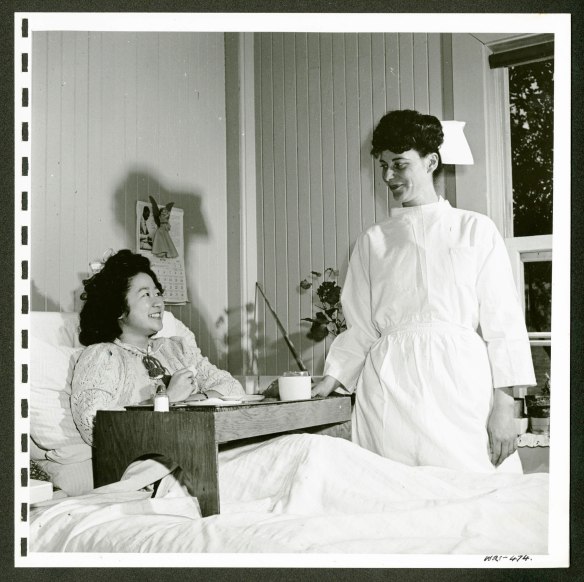

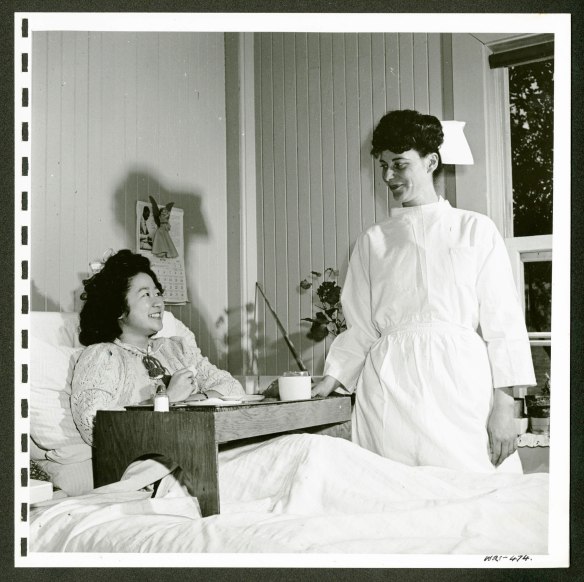

Euphemisms are employed, such as “space-saving” and “snug” for cramped, “evacuees” for internees, “repatriation” for deportation, “cottages” for internment shacks, and “settlements” and “housing centres” for the actual camps. There are “orderly rows of houses” and “tidy valleys.” The point is often made that the internees are being treated the same as other Canadians: “In camp hospitals, babies are born as in any other hospital. This happy mother chats with Dr. Burnett, director of the hospital” and “At the end of the school term Japanese evacuee students have a graduation banquet just as any other students in Canada would. Settlements are unguarded, and evacuees may visit between them, or go out for sports.”

There are descriptions such as “cheerful,” “modern,” “a fine place,” “well-equipped,” “well-stocked,” “clean,” and “as perfect as possible.” In one image of the women’s ward of the hospital at the New Denver, B.C., camp hospital, the caption writer senses “there is no doubt about the good feeling behind these smiles.” In this case, the ribboned ornament that the internee patient has pinned in her hair is perhaps evidence that the photograph was staged.

In the women’s ward of the hospital at New Denver, there is no doubt about the good feeling behind these smiles. [The photographer appears to have posed the internee patient. Notice the ribboned ornament she has clipped on the back of her head.] (e999900300-u)

Yet even though the Long photographs have been artfully and professionally staged, there is still no mistaking the posed, self-conscious smiles of people who are detained in internment camps.

When one bureaucrat in Canada’s Department of External Affairs saw Long’s images, he wrote on the file pocket: “These are excellent photographs.” However, the written comments of another bureaucrat, Arthur Redpath Menzies, dated April 26, 1943, appearing just below his colleague’s leave us with a stark reminder of the reality of the situation not revealed by the photographs themselves: “Understand from some who have been there that this spot is actually pretty grim — very cold — no work except sawing wood . . . in fact not a very pleasant spot — for Canadian citizens where only offence is their colour.” Menzies went on to become Canada’s Head of Mission in Japan in 1950 and Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to the People’s Republic of China and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in 1976.

Evacuee homes in Lemon Creek, B.C., are built with enough space in between for comfort and a garden. Each cottage accommodates one family. [Internee shacks in the Lemon Creek, B.C., internment camp] Credit: Jack Long (e999900291-u)

Some of the thousands of Japanese typeface characters used for The New Canadian, a newspaper that was published every week in Kaslo, B.C. The offices are now in Winnipeg, Manitoba. [The New Canadian began publishing in 1939, in Vancouver. It was an English-language newspaper founded to be the voice of the Canadian-born Nisei (second-generation Japanese Canadians). After the attack on Pearl Harbor and the internment of some 20,000 Japanese Canadians, it resumed publishing in the Kaslo, B.C., internment camp. A Japanese-language section was added to better serve the Issei, or first-generation Japanese Canadians. In 1945, the paper moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba, and subsequently, in 1949, to Toronto, Ontario, where it continued publishing until 2001.] Credit: Jack Long (e999900358-u)

The very modern kitchen of the Greenwood camp hospital. [Hospital kitchen at the Greenwood, B.C., internment camp] Credit: Jack Long (e999900255-u)

The original captions for these photographs expose vestiges of Canada’s colonial past. Library and Archives Canada continues to provide relevant context as a way of presenting a fuller and more equitable picture of our nation’s history. This is work of value. For, as written on the Landscapes of Injustice website: “A society’s willingness to discuss the shameful episodes of its history provides a powerful gauge of democracy.”

If you have an idea for a project like this one, please email the DigiLab with an overview of your project.

Related LAC sources

Textual documents

Case files

Related links

Gabrielle Nishiguchi is a government records archivist in the Society, Employment, Indigenous and Governmental Affairs Section, Archives Branch, at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=584)