By Ariane Brun del Re

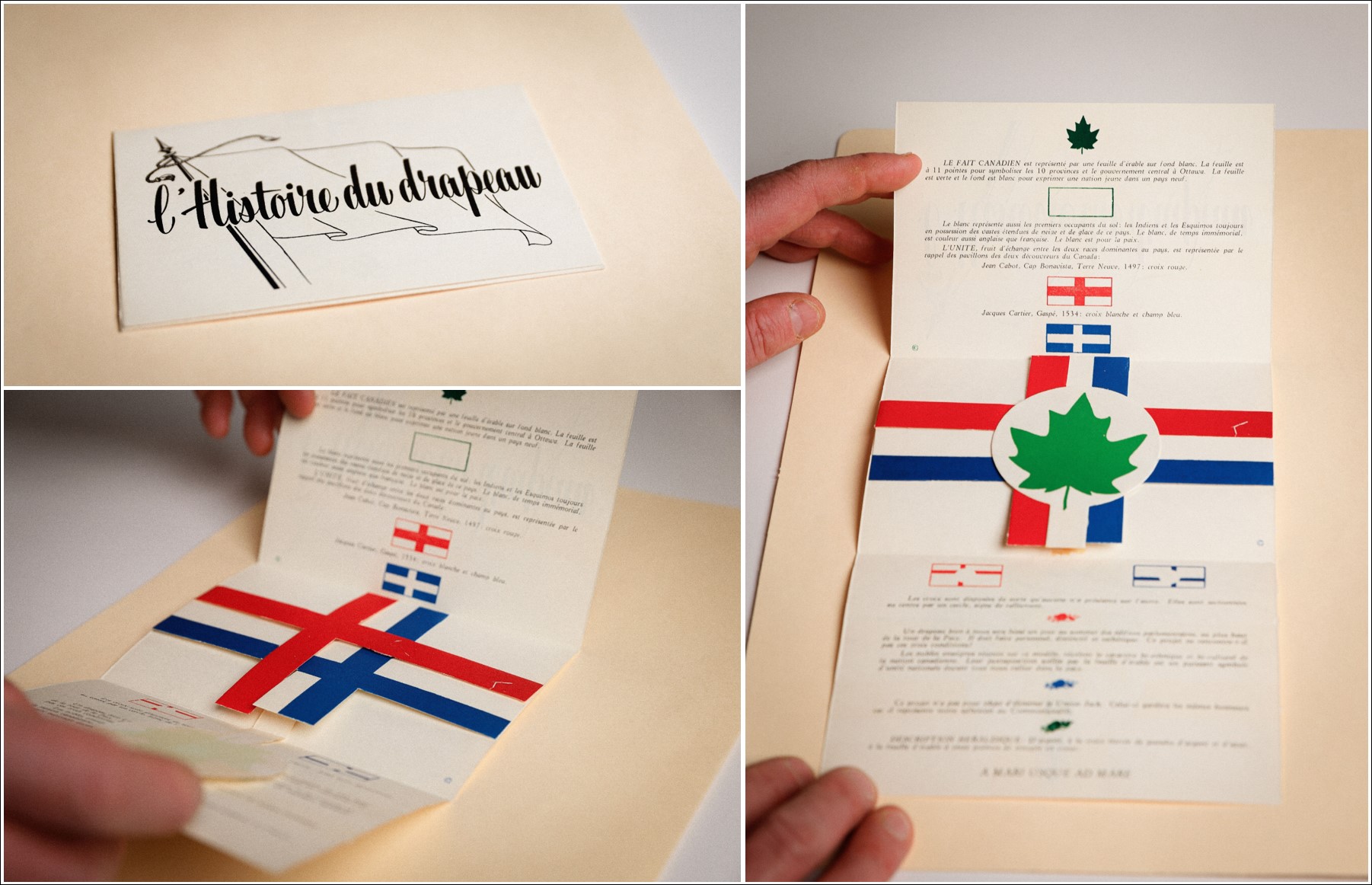

This year, Théâtre Cercle Molière, a professional theatre company located in the St. Boniface neighbourhood in Winnipeg, is celebrating its centenary. This anniversary is all the more remarkable as it marks the existence of the oldest Francophone theatre company in Canada.

Founded to perform classics of the French repertoire, Théâtre Cercle Molière turned to Québécois and Canadian theatre in the 1950s. Over the following decade, it transformed into a professional company and became one of the main hubs of Franco-Manitoban playwriting, a role it continues to play today.

Although the archival collection of Cercle Molière is preserved at the Centre du patrimoine of the Société historique de Saint-Boniface, some documents that reflect the existence and evolution of this important theatre company are part of the collections of Library and Archives Canada (LAC), notably the Gabrielle Roy fonds.

Known for winning the prestigious Prix Femina with her novel Bonheur d’occasion (1945), later translated to English as The Tin Flute, Gabrielle Roy is originally from St. Boniface. Before becoming an internationally renowned writer, she graced the stage of Théâtre Cercle Molière on multiple occasions. She became a member around 1930 or 1931, during her time teaching at École Provencher in St. Boniface. At that time, Théâtre Cercle Molière was led by Arthur Boutal, a journalist and printer by profession, who staged French plays with the help of his wife Pauline (born Le Goff), a visual artist and fashion designer. After the death of Arthur Boutal in 1941, Pauline took over the company until 1968. The certificate below, presented to Gabrielle Roy by the Province of Manitoba in honour of the theatre company’s 50th anniversary, underscores her significant involvement with Théâtre Cercle Molière:

Certificate awarded to Gabrielle Roy by the Province of Manitoba in recognition of her participation in Théâtre Cercle Molière. (e011271382)

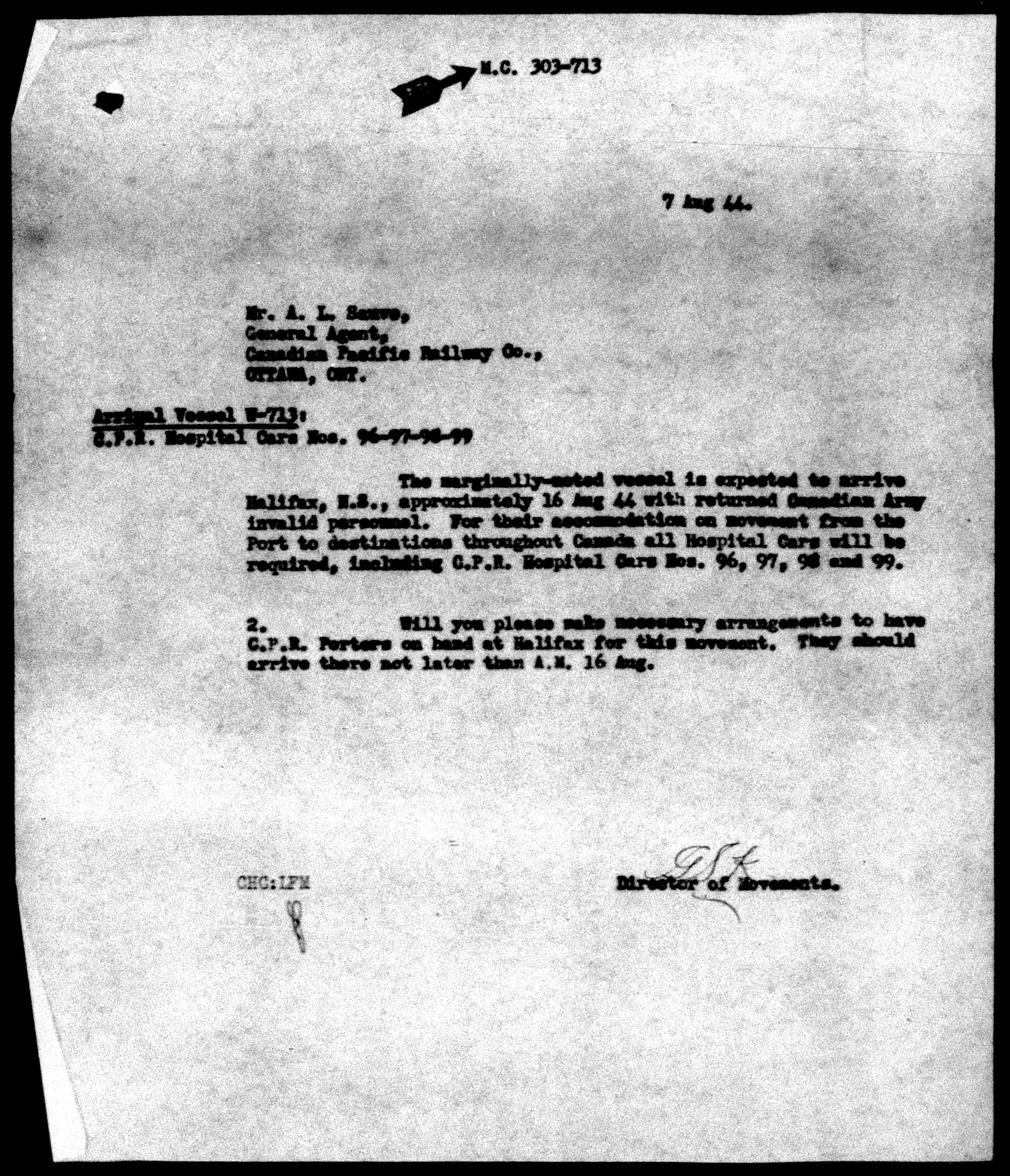

The Gabrielle Roy fonds also contains several drafts of the text entitled “Le Cercle Molière… porte ouverte…”, which she wrote around 1975 for an album intended to commemorate the company’s 50th anniversary. The article was published in the collective work Chapeau bas : réminiscences de la vie théâtrale et musicale du Manitoba français (1980). In it, Gabrielle Roy recalls the challenges faced by the members of Théâtre Cercle Molière: “The main difficulty for us, who had no resources, was always to secure a free space for our rehearsals. We wandered from place to place until, during a rather harsh winter, we ended up rehearsing—scarves around our necks—in the dimly lit and poorly heated space of a warehouse. In the end, I obtained permission from the director of Académie Provencher, where I was a teacher, to use my classroom for this purpose.” [Translation] (p. 117)

The front and back of the first page of the notebook in which Gabrielle Roy wrote the text “Le Cercle Molière… porte ouverte…” published in Chapeau bas. (e011271380)

After taking on various positions for the theatre company, Gabrielle Roy landed her first real role in the play Blanchette by Eugène Brieux, which premiered on November 30, 1933. She played the daughter of an aristocratic couple. Thanks to this play, the company stood out at the Manitoba Regional Festival, a preliminary competition that opened the doors to the new Dominion Drama Festival, which took place in Ottawa in April 1934. Against all odds, the company triumphed in the Francophone category.

Two years later, Cercle Molière once again won the Manitoba Regional Festival, with Jean-Jacques Bernard’s play Les Sœurs Guédonec. The play featured two old peasant women, one of whom, Maryvonne, was played by Gabrielle Roy and the other, Marie-Jeanne, by Élisa Houde, as shown in the program below:

Program from the 1936 edition of the Manitoba Regional Festival, during which Théâtre Cercle Molière presented Les Sœurs Guédonec, with Gabrielle Roy in the role of Maryvonne. (MIKAN 5383741)

Théâtre Cercle Molière was thus selected to participate in the Dominion Drama Festival, where it won the trophy for Best French Play for the second time. During this stay in Ottawa, Gabrielle Roy crossed paths with one Yousuf Karsh. The young Canadian photographer of Armenian descent collaborated with Ottawa Little Theatre, where he learned to photograph actors on stage, as he recounted in his book In Search of Greatness (1962): “This experience of photographing actors on stage, with stage lighting, was electrifying. [My mentor, John H.] Garo had taught me to work with daylight, where one had to wait for the lighting to be right. In this new situation, the director could command the lighting to do what he wished. The unlimited possibilities of artificial light overwhelmed me.” (p. 48) The lighting techniques he honed in the theatre, which allowed for significant contrasts between black and white, would ultimately become his trademark.

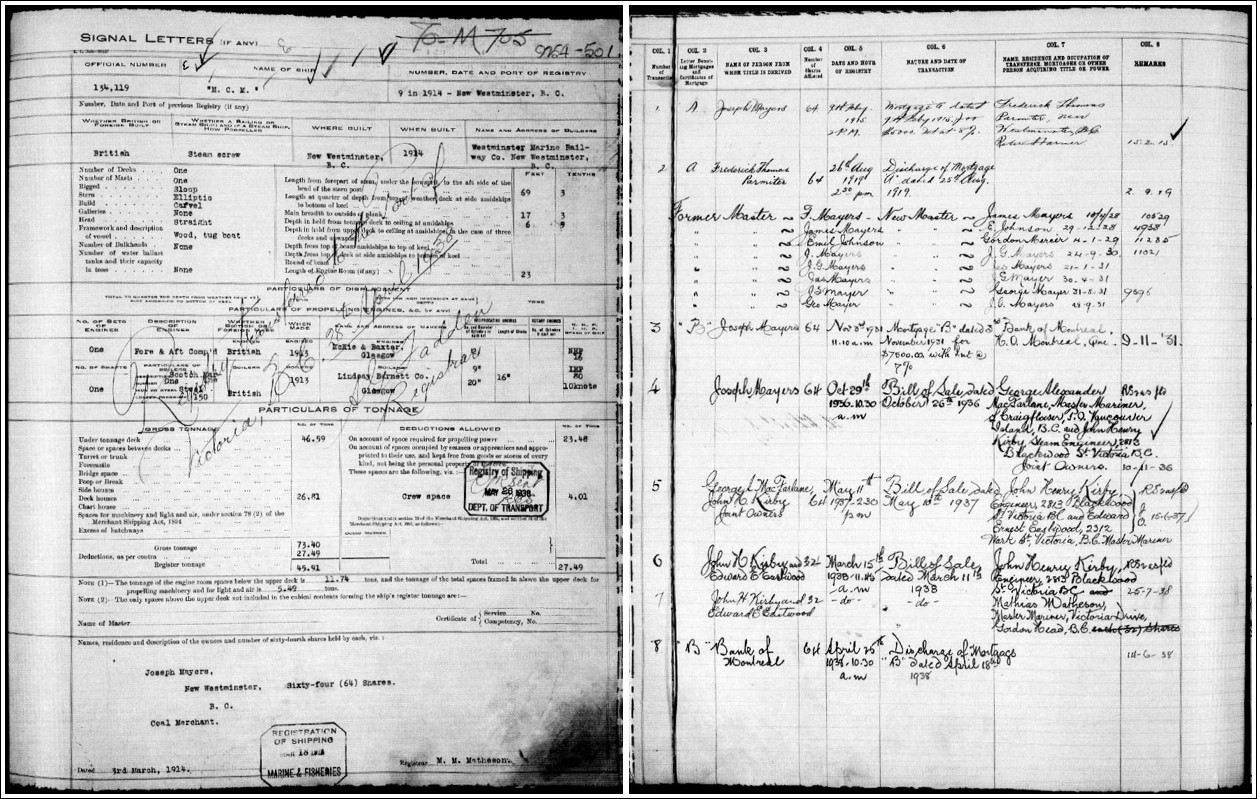

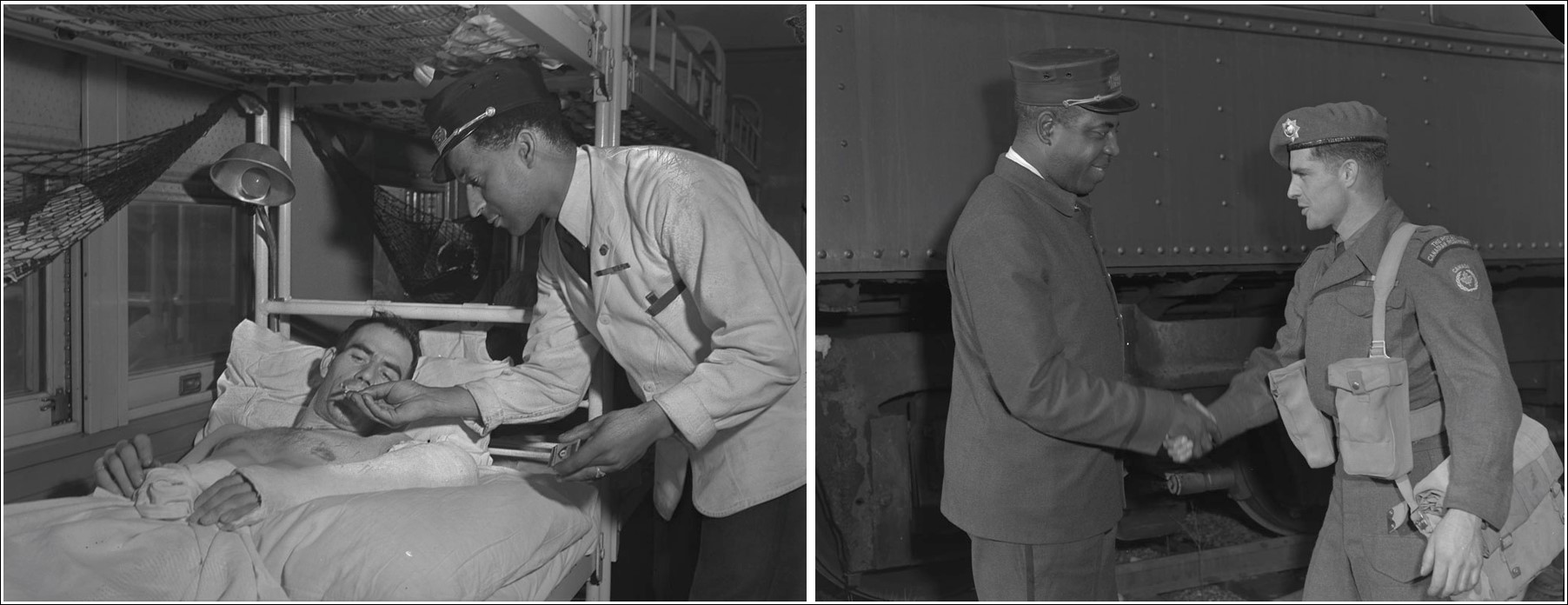

Driven by his interest in theatre, Karsh became the official photographer of the Dominion Drama Festival in 1933. LAC preserves several photographs he took of Gabrielle Roy during the performance of Les Sœurs Guédonec:

Photograph by Yousuf Karsh showing Élisa Houde (on the left) and Gabrielle Roy (on the right) in a performance of the play Les Sœurs Guédonec at the Dominion Drama Festival. (e011069771_s1)

When their paths crossed, both Gabrielle Roy and Yousuf Karsh were 27 years old. Without knowing it, they were each on the verge of an internationally renowned career, propelled by the world of theatre. The two artists would leave their mark in their respective disciplines: she, in literature; he, in photography.

Years later, while examining one of the photographs of herself and Élisa Houde taken by Karsh, Gabrielle Roy wrote: “I look at the small, yellowed photo and feel a strange shock in my heart. In the end, what was it that drove this woman [Élisa Houde], a calm and already quite elderly schoolteacher, to suddenly throw herself into such a whirlwind? What, after all, was it that drove all of us? Would the world be changed because a group of amateurs, coming from the far reaches of the country, was about to perform a play from the French repertoire in the Canadian capital? In the ethnic diversity of Manitoba, almost entirely dominated by English, what were we—this small group of French speakers, our reckless efforts, this bold hope of ours—still, to this day, I wonder how it could have possibly flourished in our isolation? A flower in the desert!” [Translation] (1980, pp. 120–121)

What is certain is that Gabrielle Roy would be transformed by this “flower in the desert,” as she so aptly put it. Her time at Théâtre Cercle Molière had confirmed her desire to write: “During rehearsals, as I sometimes discovered and expressed myself through the words of an author, I felt the desire to perhaps, one day, give voice to others. What a thrill it must be!” [Translation] (1980, p. 123)

One hundred years after its founding, Théâtre Cercle Molière remains an open house, a gathering place, and a hub of vibrant activity for Francophone theatre in Manitoba and beyond. It has propelled the careers of many artists and left a lasting impact on generations of spectators. Happy anniversary, Théâtre Cercle Molière!

Additional resources:

- Gabrielle Roy, une vie : biographie, François Ricard (OCLC 35940894)

- Chapeau bas : réminiscences de la vie théâtrale et musicale du Manitoba français (OCLC 10112702)

- In Search of Greatness: Reflections of Yousuf Karsh, Yousuf Karsh (OCLC 947443)

- Website of the Théâtre Cercle Molière

- Gabrielle Roy fonds, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN 3672665)

- Yousuf Karsh fonds, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN 138136)

- The Dominion Drama Festival—Theatre Canada fonds, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN 99527)

- Performing Arts Collection, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN 106737)

Ariane Brun del Re is an archivist of French language literature in the Cultural Archives Division at Library and Archives Canada.