July 1, 2023, marks 100 years since the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923, commonly known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, was passed into law. Library and Archives Canada (LAC) has recently opened and digitized records arising from the Act’s mandatory registration of “every person of Chinese origin or descent in Canada.”

The first Chinese people arrived in Canada as artisans in 1788. From 1858 to 1885, a significant number of Chinese labourers came to complete the Canadian Pacific Railway across British Columbia. The Canadian government’s restrictions on Chinese immigration began thereafter with passage of the Chinese Immigration Act, 1885. Until its repeal in 1947, this legislation underwent many amendments to discourage immigration from China. Early amendments in 1900 and 1903 increased the amount of the Chinese head tax as a financial barrier. The last amendment, in 1923, banned all further Chinese immigration. In this blog post, I will refer to the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923 as the Chinese Exclusion Act, or simply “the Act.”

Newly opened Chinese immigration records: C.I.44

LAC’s holdings include extensive Chinese immigration records from this important period for Chinese Canadian genealogy. These include ledgers and forms on the registration and identification of Chinese people upon entry, and on their movements in and out of the country.

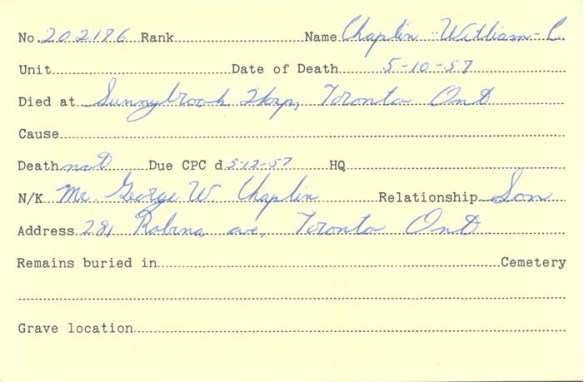

Of special interest is the recent opening of previously restricted C.I.44 forms created through section 18 of the Chinese Exclusion Act. It required “every person of Chinese origin or descent in Canada” to register with an immigration, customs or Royal Canadian Mounted Police authority within 12 months of the passing into law of the Act on July 1, 1923.

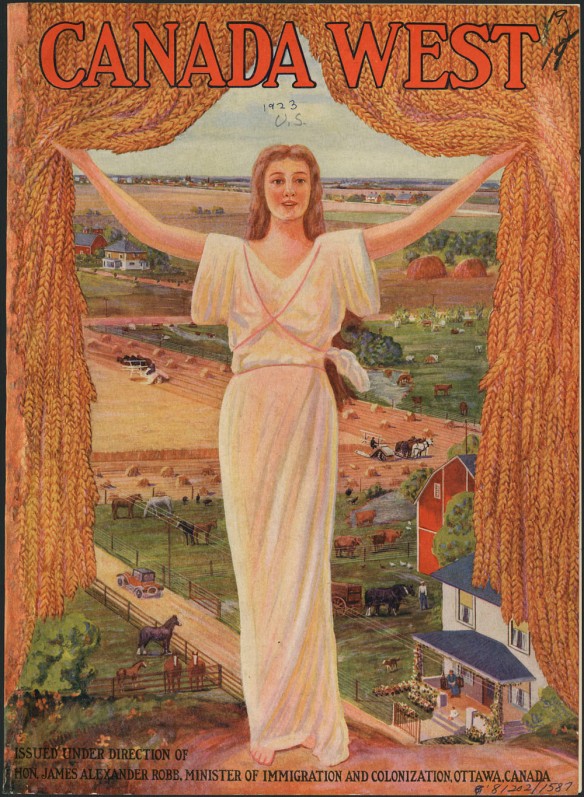

Section 18 was translated into Chinese and posted as a 69 cm by 123 cm (approximately 2 ft. by 4 ft.) public notice with a list of registrars across Canada. Those who failed to comply with registration were “liable to a fine not exceeding five hundred dollars, or to imprisonment for a period not exceeding twelve months, or to both.”

Poster on Chinese immigration giving public notice of section 18 of the Chinese Exclusion Act and its registration requirement (e010833850)

Each registration was documented in a one-page form numbered “44” in the government’s Chinese Immigration (C.I.) recordkeeping series. By the one-year registration deadline of June 30, 1924, over 56,000 Chinese people living in Canada were registered, each recorded by a C.I.44 form. A further 1,500 Chinese people who were absent from Canada registered upon their authorized return. The last form was completed in 1946, a year before the Act was repealed.

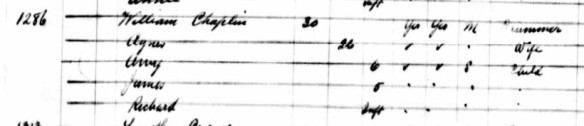

The C.I.44 form is a significant addition to Chinese Canadian genealogy resources. It records an ancestor’s name and known alias(es), address, occupation, age, marital status, and the name and address of their spouse and/or children in Canada, and it includes a photograph.

For those of Chinese origin (born in China), the form consolidates information on the individual’s entry into Canada. This includes their place of birth (village/city and district/province in China), original port of admission, conveyance (ship), original date of arrival, amount of head tax paid, and serial number of C.I. landing or replacement certificate in their possession (C.I.5, 28, 30 or 36). This information is otherwise dispersed in LAC collections, across Chinese immigration records and passenger lists.

The form also recorded the individual’s height, any facial marks and physical peculiarities, remarks made by the immigration official, and any existing file numbers.

C.I.44 form of Louie Song, 1924; RG76-D-2, Reel T-16181, Image 01453

Those born in Canada of Chinese descent were identified by the government as “native-born,” and a number of sections of the C.I.44 form did not apply to them. These individuals were predominantly minor children in the registration year. Their birthdate, details of birth registration and names of parents in Canada often appear as remarks.

C.I.44 form of Helen Mah Yick, 1924; RG76-D-2, Reel T-16174, Image 00690

Access and search C.I.44 records

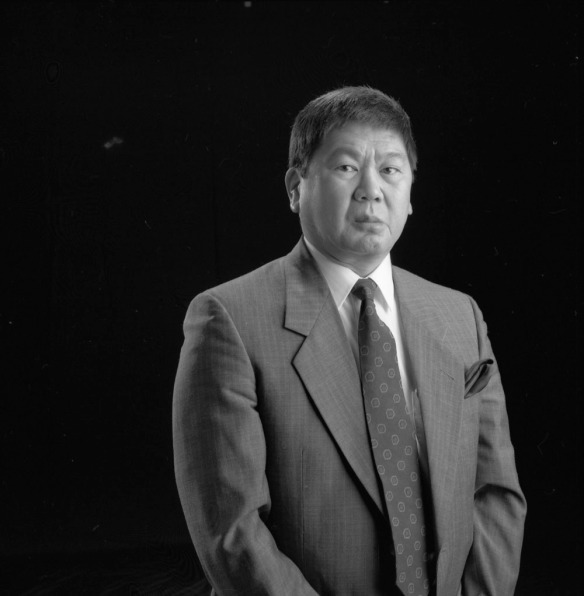

The C.I.44 records are an important resource for Chinese Canadian genealogy and research on Chinese Canadian history. Each C.I.44 form records where in Canada an ancestor had settled, what work they were doing and their family structure. Often they were using an English or Anglicized name (alias) to fit into Canadian society; their photograph shows how they were grooming and dressing themselves in the Western style.

As a result, these records document settlement patterns of Chinese people in Canada. Taken together, they provide a comprehensive snapshot of the Chinese Canadian community as it entered its darkest period, defined as the 24 years that the Chinese Exclusion Act was in force.

Search these records if your ancestor was:

- Chinese (immigrant or native-born) AND EITHER

- living in Canada in 1923/1924 OR

- living abroad in 1923/1924 and legally returned to Canada before 1947

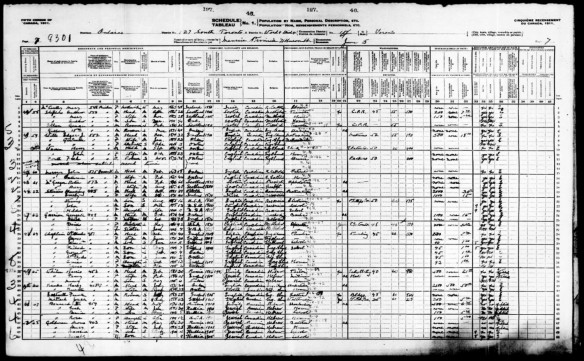

The C.I.44 records consist of 29 digitized microfilm reels with the C.I.44 forms and a corresponding index card system. They can be searched manually or as indexed by FamilySearch and Ancestry.

Additional resources

- C.I.44 forms and indexes

- C.I.44 microfilm reels

- C.I.44 reference guide

- Chinese immigration records

- Chinese Immigration Act, 1923

- FamilySearch

- Ancestry

June Chow is Community Archivist for The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act, a community-based commemoration that spans a public exhibition, a community-based archival collection and the engagement of public archives. The Paper Trail team initiated the opening of these records through an access to information request in 2021. June subsequently spent time at LAC on their access as a Master of Archival Studies student in the University of British Columbia School of Information prior to her recent graduation. She is now also working as a Special Collections Archivist with the Chinese Canadian Archive at the Toronto Public Library.