By Ashley Dunk

In Library and Archives Canada’s Victoria Cross blog series, we profile Canada’s Victoria Cross recipients on the 100th anniversary of the day they performed heroically in battle, for which they were awarded the Victoria Cross. Today, we remember the last Canadian soldier of the First World War to receive the Victoria Cross, Sergeant Hugh Cairns, for his bravery at Valenciennes, France.

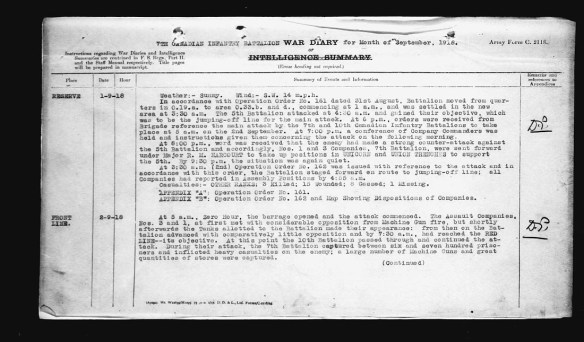

Sergeant Hugh Cairns, VC, undated (a006735)

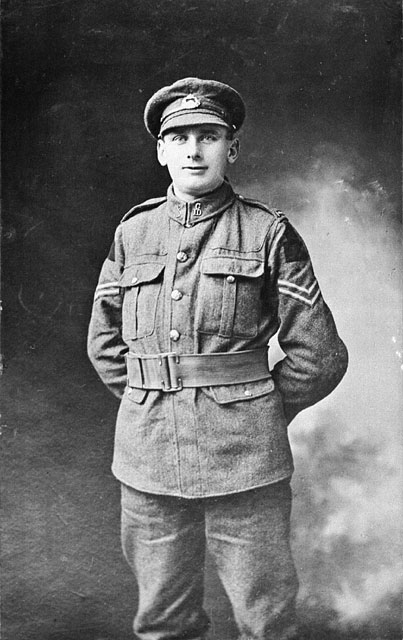

Born in Ashington, Newcastle upon Tyne, England, on December 4, 1896, Hugh Cairns and his family immigrated to Canada and settled in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Cairns was a plumber before the war. Hugh and his older brother Albert Cairns both enlisted on August 2, 1915 and August 11, 1915, respectively, in Saskatoon. They both joined the 65th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), which was absorbed into the 46th Battalion on June 30, 1916 On September 10, 1918, Albert died of head wounds caused by a shell.

Hugh Cairns served in France, proving his determination and resilience as a soldier on several occasions. He was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal on August 25, 1917 as a private. He was promoted to corporal in the summer of 1918, then to sergeant three months later.

A Canadian post in Valenciennes, November 1918 (a003355)

Through October and into November 1918, the Canadians continued their assault on the German lines. Despite German efforts to stubbornly defend their retreating lines, the Allies’ persistent offensives resulted in heavy German losses, the capture of thousands of prisoners, as well as dozens of kilometres in ground gained. By November 1, 1918, the Germans were clinging to the city of Valenciennes and maintaining their stronghold near Marly.

The push into Valenciennes from the 46th Battalion’s “A” Company included an assault on a two-platoon frontage with one support platoon. Cairns was leading the support wave platoon. The Canadian barrage opened at 5:15 a.m. and the platoons began to move toward their objectives. After advancing about 500 yards, they were met with heavy machine gun fire from their left. The platoons pushed on, squashing the resistance from the German machine guns, capturing prisoners and weapons along the way.

Canadians entering Valenciennes over an improvised bridge, November, 1918 (a003376)

As the advance inched along, the Company was held up by very heavy machine gun fire. Under a spray of bullets, Cairns and other soldiers moved to outflank the gun. Crawling on their hands and knees, under cover from friendly rapid machine gun fire, the party succeeded in closing in on the battery. They seized 3 field guns, a trench mortar, 7 machine guns, and over 50 prisoners. Cairns went on to lead his men to capture the railway and establish a post.

As Cairns was heading off to examine a nearby factory, a German soldier opened direct fire on him with an automatic rifle from a nearby post. Cairns, wielding a Lewis gun, made a run for the post of German soldiers, and fired. He killed and wounded many German soldiers in his assault as they ran for a nearby courtyard.

The flooded railway station at Valenciennes, November, 1918 (a003452)

Later, Cairns and another soldier were patrolling the city when they entered a courtyard and found 50 German soldiers. While in the process of taking them prisoner and confiscating their weapons, a German officer grabbed for his pistol and shot Cairns through the stomach. In retaliation, Cairns opened fire, killing or wounding about 30 German soldiers. The would-be German prisoners, realizing they needed to fight for their lives, descended upon Cairns and opened fire. Cairns was shot through the wrist, but continued to fire his Lewis gun at the enemy. He was again shot through the hand, nearly taking it off, and breaking his Lewis gun. Cairns threw the useless gun in the face of a German soldier who was firing at him, knocking him over. With his remaining strength, Cairns staggered to a gateway and collapsed, where he was carried off by his comrades.

French nuns and civilians in Valenciennes greet the first Canadians entering the town, November, 1918 (a003578)

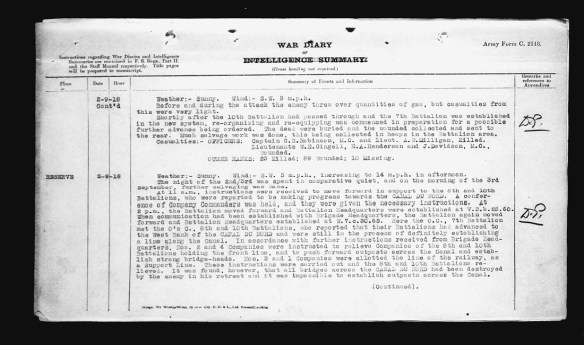

Cairns’ heroic maneuvers and self-sacrifice are detailed in the 46th Battalion’s war diaries for November 1918 (pp. 21, 22, 23), where he is mentioned by name throughout the whole account. He is one of several names given special recognition for his actions in Valenciennes. His efforts and bravery helped his company achieve their objectives. By the end of the day, the Canadian Corps captured approximately 1,800 German soldiers and killed more than 800 men. The Canadian losses including Cairns were 80 killed, and approximately 300 wounded.

French civilian woman kissing a Canadian soldier after the Canadians cleared the Germans out of Valenciennes, November 1918 (a003451)

Cairns died of his wounds on November 2, 1918 and was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously.

Cairns is buried at Auberchicourt British Cemetery in Nord, France.

Several dedications have been made in his memory, honouring his gallantry. The town of Valenciennes renamed one of its main streets to Avenue du Sergent Cairns. His parents travelled to France to attend the civic ceremony held on July 25, 1936. Back in Canada, an elementary school is named after him, Hugh Cairns V. C. School, in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. The 38 Combat Engineer Regiment armoury in Saskatoon bears his name, Sgt. Hugh Cairns VC Armoury.

His Victoria Cross is on display at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, Ontario.

Library and Archives Canada holds the digitized service file of Sergeant Hugh Cairns.

Ashley Dunk is a project assistant in the Online Content Division of the Public Services Branch of Library and Archives Canada.