By Heather Campbell

Content warning: This blog contains graphic content (death/medical/amputation) that may be offensive or triggering to some readers.

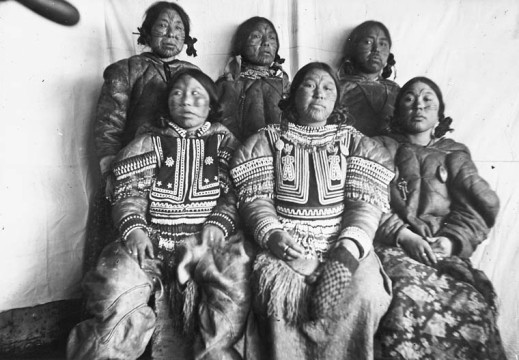

Wedding of Wilfred and Beatrice Shiwak; original title: A wedding party, at Rigolet. Wilfred and Beatrice stand in the centre, while Kirkina Mucko kneels between Wilfred’s mother and Wilfred (e011439717)

When I first began working at Library and Archives Canada (LAC) in 2018, I naturally did a quick search to see what we had from my hometown in Labrador in the collection. I simply typed “Rigolet” and got a few hits, including one record that had yet to be digitized: “A wedding in Rigolet, 1923.” Because it was not digitized, I put it on the back burner and forgot about it until last summer, when I was searching through the International Grenfell Association (IGA) collection from the same time period. I thought I would give it a shot and ordered the box to take a look. When the photos came, I flipped through quickly, looking for that photo; I just had a hunch it was going to be something interesting. After all, the population of my community is only 320, so I was bound to know the family and their relatives.

I finally found it at the back of the batch.

They looked familiar.

Wait, I know that face.

Once, many years ago, I drew a portrait of him for my grandmother’s Christmas present, so I knew that face well. It was indeed him, my great-grandfather “Papa Wilfred,” and standing to his left was my grandmother’s mother, Beatrice! For all those years, the photo was tucked away in the archives, and I could finally show it to my family members back home!

I posted the image to Facebook, tagging Project Naming in the hope that we might be able to identify more people in the photo. Within minutes, we were in luck. The woman standing to his right is his mother, Sarah Susanna, and kneeling between them is well-known Inuk nurse Kirkina Mucko (born Elizabeth Jeffries). Reports vary, but local lore says that Elizabeth’s mother was in labour and her father went to find a midwife. When he got back to their home, his wife and their newborn baby had died, and little Elizabeth, age two, had severe frostbite on her legs and gangrene had set in. There were no doctors in the vicinity. He made the difficult decision to amputate Elizabeth’s legs himself using an axe. To stop the bleeding, he put her legs in a flour barrel! An article from years later states that when the local doctor Wilfred Grenfell (who later became Sir Wilfred Grenfell) learned of her story, he wept. Consequently, Grenfell took Elizabeth to the orphanage in St. Anthony, Newfoundland, and was able to raise money to provide her with artificial limbs. She travelled with him to the United States and Mexico to help raise funds for the IGA. The IGA provided health care to everyone in Labrador at that time, as well as conducting other charitable endeavours.

People from 20 miles around gathered for the annual service of the Anglican clergyman Parson Gordon, who is wearing his robes and standing toward the right of the group (e011439717)

Later, a doctor in Boston, for reasons unknown, changed her name to Kirkina. As stated by other Inuit regarding this era, Inuit children in southern hospitals were sometimes treated like pets. As such, they were taken home and raised by hospital staff, never to be heard from again by their families in the Arctic. I presume that this attitude is what led the doctor to change Elizabeth’s name. Her name changed once more when she was married and became Kirkina Mucko.

During the 1918 Spanish influenza epidemic, Kirkina lost her husband and between three and six of her children (some accounts may have included her stepchildren, which would explain the discrepancy). Spurred by this immense loss, Kirkina decided to become a nurse. She received her training and went on to specialize in midwifery. Her career spanned 36 years! Many mentions of Kirkina Mucko and her amazing story can be found in newspaper articles as well as in writings from the IGA, many of which are in the holdings at LAC. In 2008, the local women’s shelter in Rigolet was named Kirkina House as a tribute to her strength and perseverance.

This blog is part of a series related to the Indigenous Documentary Heritage Initiatives. Learn how Library and Archives Canada (LAC) increases access to First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation collections and supports communities in the preservation of Indigenous language recordings.

Heather Campbell is an Inuk artist originally from Nunatsiavut, Newfoundland and Labrador. She was a researcher on the We Are Here: Sharing Stories team at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner.jpg?w=584)

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=519)