By Ellen Bond

In the 1970s, there were two shows I looked forward to every weekend: The Wonderful World of Disney on Sunday (feel-good stories) and The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Hour (cartoons) on Saturday. It wasn’t the ACME dynamite or the crazy coyote that scared me on Saturday—it was the quicksand! Being stuck in cement-like mud sounded horrendous to me. So imagine my feelings when I learned that most of Ottawa is built over a massive amount of Leda clay, which can liquefy from ground tremors, forming a type of quicksand. Quicksand? Here in Ottawa? Not only in the desert of Wile E. Coyote? Yikes!

A map showing the former location of the Champlain Sea after the last period of glaciation (Wikipedia) Credit: Orbitale

The Champlain Sea and the formation of Leda clay

After the last ice age, the climate warmed and the snow and ice melted. Massive spillways, which carried melting glacial waters and looked like enormous rivers, moved the water away from the remaining glaciers and sometimes formed lakes. In the area now known as the Ottawa Valley, a vast inland shallow sea formed 15,000 years ago. Geologists named it the Champlain Sea. What is unique about this sea is the Leda clay that was deposited in areas of deeper water.

You may wonder what happened to the Champlain Sea and why these lands are not still underwater. There are two reasons: evaporation and the rebounding of land once freed from the incredible weight of a 1- to 3-kilometre deep glacier. The land previously under the glaciers in North America is still rebounding today, 15,000 years later!

Leda clay (also known as quick clay and Champlain Sea clay) was formed by sediment eroding from the earth and landing at the bottom of the sea. The Champlain Sea was full of both fresh water from the glacial melt and salt water from the ocean. When salt molecules combine with the clay molecules, it makes a stable clay. But if fresh water infiltrates the clay and washes away the salt, the clay becomes very unstable. An unstable clay molecule is prone to liquefying.

Why doesn’t Leda clay liquefy more often?

You may wonder why the Leda clay under Ottawa and the lands around the St. Lawrence River doesn’t liquefy all the time. For the most part, the clay is underneath the surface and away from fresh water, and so is very stable. However, earth tremors, whether natural (earthquakes, erosion) or human created (explosions, blasting, digging), can allow fresh water to seep into the Leda clay, removing the salt molecule. If that clay is on a hill or on the edge of a winding river, this leads to landslides.

Leda clay has been found responsible for over 250 landslides in Canada alone. In the Ottawa area, Leda clay was responsible for the Canadian Museum of Nature building’s tower sinking in 1915 and, more recently, holding up new developments in Ottawa South in 2021. It was also responsible, in part, for the Rideau Street sinkhole that appeared with train construction in downtown Ottawa in 2016.

The landslide disaster at Notre-Dame-de-la-Salette

Notre-Dame-de-la-Salette is in the area formerly covered by the melt waters from the Champlain Sea. The village is northeast of Ottawa, in Quebec, and marked by an orange star in the map of the Champlain Sea above.

Disaster struck in the middle of the night in Notre-Dame-de-la-Salette on April 26, 1908, when a riverbank of the frozen Lièvre River gave way. Fresh water had infiltrated the Leda clay molecules, making them unstable, and the riverbanks collapsed, propelling a wave of mud, ice and ice-filled water across the river and into the town. Thirty-four people lost their lives and at least twelve homes were destroyed.

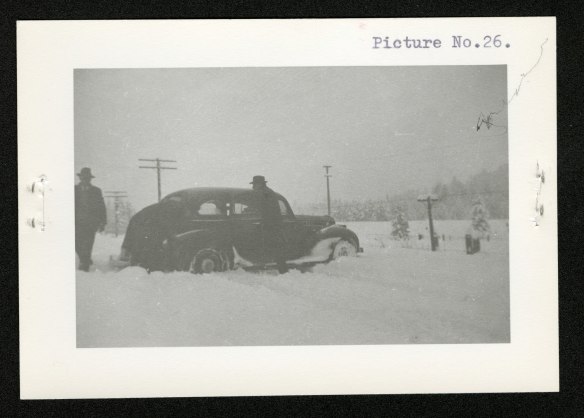

Looking up Lièvre River from Notre-Dame-de-la-Salette, Quebec (a040044-v6)

Water moves in a straight line until it meets resistance. In this historical photo of the area, the water in the river is flowing towards the riverbank (blue arrow), and it was here that the riverbank gave way. Labelled in green you can see the stumps left behind following the clearcutting of trees along the bank. Without the layer of trees to protect the bank, the entire area was prone to eroding quicker than before the cut. Some of the village of Notre-Dame-de-la-Salette can be seen across the river from where the landslide occurred. At this time, there is no island in the middle of the river, and there are houses close to the river on the town side. Comparing this image to ones after the slide, there is a stark difference. Look for changes to this scene in some of the photos that follow, especially house placement.

Southeast view of the Lièvre River Valley and Notre-Dame-de-la-Salette (a044070-v8)

Another old photo from the LAC collection shows the river flowing away from the viewer. Look closely, and you can see where the earth gave way and the island formed in the middle of the river after the landslide.

Former town site of Notre-Dame-de-la-Salette, Lièvre River, Quebec. Photo looks upstream. (a020267)

In the photo above, the river is flowing towards the viewer, and you can see the bridge crossing the river, north of town. A red arrow points to where the riverbank gave way during the landslide. A new island formed in the middle of the river from the sediment and material moved in the slide. The other change is that there is now a clearing where the town site had been—people rebuilt the town further away from the river.

A white cross stands on the edge of where the land gave way in 1908, leaving a scar on the land still visible today. Photo credit: Ellen Bond

The colour photo above was taken recently, and you can see the area affected (where the land gave way along the ridge), the island formed from the slide and a memorial white cross on the hill.

The above photo looks downstream at the slide location. The slide area is shown in yellow, and you can see the ridge above. On the left, you can see the edge of the island that formed after the slide.

A memorial plaque located near the landslide area. It describes the event and lists the names of the victims. Photo credit: Ellen Bond

Although this landslide occurred over 110 years ago, the effects can be still seen and felt today. In the middle of the night, due to no fault of their own, 34 people lost their lives tragically and unexpectedly. Their names, in each family group, were

- Alexina, Amanda, Adélard and William Charron-Lamoureux,

- Cléophas Deslauriers, Célina, Damien, Wilfrid, Albert, Lucien, Béatrice and Alice Deslauriers-Paquin

- Émélie, Florimond and Alias Desjardins-Gravelle

- Émélie, Daniel, Eddy, Arthur, Angus and Henri Lapointe Labelle,

- Rose-Anna, Camille, David, Emma, Rose and Albert Larivière-Charron,

- Alexina, Arsidas, Wilfrid, Florida and Anna Murray-Légaré

- Georges Morrissette

- Adélard Murray

The power of the earth is incredibly strong, and those that inhabit the planet are sometimes the unfortunate recipients of its fury. It happens in regions affected by hurricanes. It happens where two of the Earth’s plates meet and are moving in different directions. It happens where Leda clay has formed. As humans, we cannot control this power. In Notre-Dame-de-la-Salette, the people have adapted to the Leda clay by moving their houses away from the river. Unfortunately, lives were lost learning this lesson. RIP to all of the victims and their families.

Looking across the river to the slide location. The ridge is visible as is the island. Photo credit: Ellen Bond

Additional Resources

- Notre-Dame-de-la-Salette “Recueillement” by Béla Simó

- Mon village, mes ancêtres : Notre-Dame-de-la-Salette, 1883-2008 by Pierre-Louis Lapointe

(Click on “More Information” to open the PDF) - The night the earth moved from the Ottawa Citizen dated April 26, 2008

- Ottawa Citizen article from April 27, 2020

Ellen Bond is a project assistant with the Online Content team at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg?w=584)