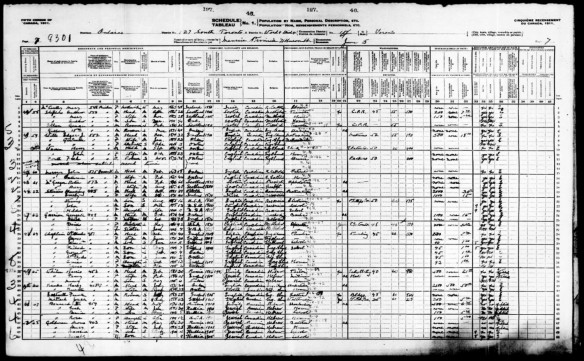

In preparation for the release of the 1931 Census returns, some of us at Library and Archives Canada have done a lot of reading. We thought we’d share a few census publications that piqued our interest.

Instructions to Commissioners and Enumerators, Seventh Census of Canada, 1931, and Instructions to Enumerators, Census of the Northwest Territories [and certain other northern areas], 1931

Ready to read cursive handwriting? Although these instructions don’t help us decipher cursive (alas!), they do help us understand some abbreviations used in the census returns. Enumerators were instructed to use certain abbreviations, such as “(ab)” for “absent.” The instructions also detail what enumerators were told to record and how; for instance, who was to be considered part of the family for the purpose of enumeration. Sara Chatfield’s recent blog, “How to conduct a census – in 1931,” highlights elements new to the instructions in 1931.

Note that the Dominion Bureau of Statistics issued separate Instructions to Enumerators for the 1931 Census of the Northwest Territories, certain parts of Yukon, eastern shore of Hudson Bay north of Great Whale River, and southern shore of Hudson Strait and Ungava Bay. This separate set of instructions was issued because the census of population in these areas was recorded using a separate form (Form I-N.W.T.), and also because the census in these northern areas was taken earlier—at any convenient time between October 1, 1930, and June 1, 1931, rather than as of June 1, 1931—for logistical reasons.

Screenshot of cover page of Instructions to Enumerators, Census of the Northwest Territories [and certain other northern areas], 1931 (Library and Archives Canada/CS98-1931I-1-eng, title page)

The Administrative Report on the Seventh Census of Canada provides good reading for those of us who are curious about what the Dominion Bureau of Statistics did with the handwritten census returns after they arrived in Ottawa from across the country.

The “New Census Machines—Sorter-Tabulator and Verifier” section (pages 58–62) provides insight into how the information in the handwritten census returns was processed at the Dominion Bureau of Statistics. This section explains what the Bureau did with the census returns that we preserve at Library and Archives Canada. For the purposes of sorting and tabulating results, Bureau employees punched a general card for each individual listed in the census returns, meaning that the Bureau must have punched over 10 million general cards. Can you decipher the information recorded on the following general card? For an answer, see page 59 of the report.

A general card used by the Dominion Bureau of Statistics for sorting and tabulating activities during the 1931 Census (OCLC 796971519)

A second type of card, the family and occupation card, “was used for the purpose of compiling statistics relating to the Canadian home and family” (page 59).

A family and occupation card used by the Dominion Bureau of Statistics for sorting and tabulating activities during the 1931 Census (OCLC 796971519)

Sorting, counting and recording proceeded mechanically. The Dominion Bureau of Statistics had developed, in-house, a new sorter-tabulator for the 1931 Census, increasing possibilities for cross-analysis “several thousands of times” (page 60). The Administrative Report describes how this new sorter-tabulator worked and features a photograph—admittedly grainy—of the machine as well as of others, such as the verifier and the gang-puncher, on pages 72–73.

Employees working on the 1931 Census in the punching room at the Dominion Bureau of Statistics (from Statistics Canada’s 2018 online HTML version of Standing on the shoulders of giants—History of Statistics Canada: 1970 to 2008, by Margaret Morris)

Another section in the Administrative Report, “The Field Work” (pages 51–56), describes the task of enumerating each person within the borders of Canada at that time. Additionally, in this section, the Bureau reports not only the number of enumerators involved but also the enumerators’ regular occupations. Among the 13,886 people working temporarily as enumerators, their regular occupations were most frequently the following:

A listing of the “most numerously represented occupations” of 1931 Census enumerators, from the Administrative Report on the Seventh Census of Canada (OCLC 796971519)

The Administrative Report was republished as Part I of the Dominion Bureau of Statistics report on the Seventh Census of Canada, 1931, Volume I, Summary (Ottawa, King’s Printer: 1936).

“Radio sets in Canada, 1931”

New for the census of population in 1931 was a question about radio sets. The Dominion Bureau of Statistics 1932 bulletin “Radio sets in Canada, 1931” provided a preliminary count of the result. The bulletin tabulated radio sets by province, census division and urban centre of more than 5,000. People in Montréal—listed as the biggest urban centre, with a population of 818,577—owned a total of 70,164 radio sets. However, Toronto—listed as the second-biggest urban centre, with a population of 631,207—reported the highest total of radio sets owned: 91,656.

A radio features in the background of this January 1931 photograph of Richard Finnie typing notes in Kugluktuk, Nunavut (a100695)

Not all of our reading was pleasant. Reading through publications from the 1930s is a reminder of the varied ways in which racism, sexism and colonialism were manifest at that time. Those attitudes shaped the taking of the census and have had enduring legacies into the present.

We’ve mentioned just a few examples of what we’ve been reading from among the many publications that preceded or resulted from the 1931 Census of Population. Generally speaking, the Dominion Bureau of Statistics released preliminary counts and summaries as soon as possible after the 1931 Census, as it did with “Radio sets in Canada, 1931.” The Bureau subsequently published definitive findings and analyses in the multi-volume official report of the 1931 Census. Statistics were published in volumes I through XI during the years 1933 to 1936, and additional thematic analyses on topics such as “housing in Canada” and the “lengthened dependency of youth” were published as volumes XII and XIII in 1942. These publications and many more are found in the library collections at Library and Archives Canada. Many such publications have been digitized by Statistics Canada and made available on the Internet Archive and the Government of Canada Publications catalogue.

If you’re interested, we invite you to browse some of the published heritage from the 1931 Census of Canada. And good luck interpreting cursive handwriting in the census returns!

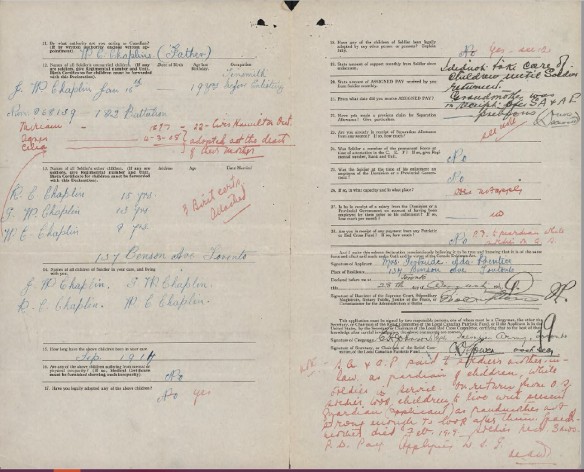

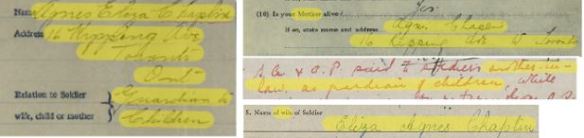

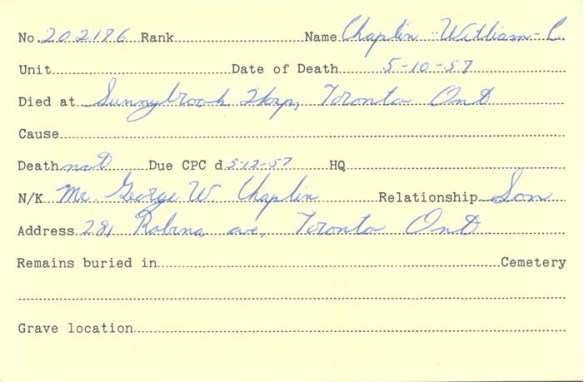

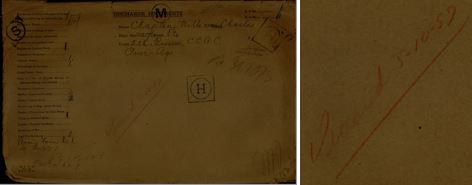

![A typed and handwritten document, titled Particulars of Family of an Officer or Man Enlisted in C.E.F. [Canadian Expeditionary Force], from William Charles Chaplin’s service file in the Personnel Records of the First World War database.](https://thediscoverblog.files.wordpress.com/2021/08/pic9.jpg?w=584)