By Ariane Gauthier

Alberta Sugar Makes Delicious Things to Eat is a booklet created by Canadian Sugar Factories some time in the 1930s to promote its production of “pure” Alberta beet sugar. This sugar is refined from thousands of sugar beet farms in the province, and the booklet includes a two-page exposé on the nuances of this farming culture. A great emphasis is put on what was then the most modern of mass-farming technology, likely to legitimize sugar beet farming, which was new and in fierce competition with the very popular (and largely preferred) cane sugar.

The booklet cover of Alberta Sugar Makes Delicious Things to Eat. (OCLC 1007785982)

This booklet is available in Library and Archives Canada’s published collections catalogue Aurora: OCLC 1007785982.

While the history of sugar in Alberta is quite interesting, what attracted me to this booklet was the historical context surrounding the publication of this book: the Great Depression. The booklet mentions that Canadian Sugar Factories started business in 1925, which means they only had about five years before the economic collapse derailed production and profitability. Perhaps this is why there is such a sense of desperation or defensiveness in dispelling misconceptions surrounding beet sugar at the end of its biographical exposé:

The cropped second page of The Story of Alberta Sugar, specifically the subsection “Beet sugar is the same as cane sugar,” from the booklet Alberta Sugar Makes Delicious Things to Eat. This is the note on which this corporate “biography” leaves the reader. Notice how points 1, 3, 4 and 7 essentially argue the same thing: that it is impossible to distinguish beet sugar from other types of sugar. (OCLC 1007785982)

Like many cookbooks published during the Great Depression, the recipes have an important emphasis on affordability and longevity: food had to be cheap, and it had to last. However, with this booklet emphasizing Alberta sugar, most of the recipes reflect sweets and pastries, which are decidedly neither of those things.

Nevertheless, I chose this booklet for its aesthetics and because the snow whirl chocolate roll recipe seemed tasty!

The recipe for the snow whirl chocolate roll from Alberta Sugar Makes Delicious Things to Eat. Remarkably, it lists the oven temperature and cooking duration! (OCLC 1007785982)

As I flipped through the pages of the booklet, I noticed there was a section on frosting and icing. In keeping with the spirit of vintage cooking, I decided to pick one of each to pair with the cake: I chose the mountain cream icing for the filling and the fudge frosting for the exterior.

Frostings and Icings page from Alberta Sugar Makes Delicious Things to Eat. (OCLC 1007785982)

In both instances I was pleasantly surprised by the number of details that would guide the recipes I planned to undertake. Not only was I given oven temperatures, I was also given cooking times! The only thing I was truly missing was a Fahrenheit or Celsius indication of the “soft-ball” stage, but my handy-dandy candy thermometer filled in the blanks (the answer is about 240 ⁰F or 115 ⁰C). I was then off to the races!

I started by gathering all my ingredients.

All the required ingredients for the snow whirl chocolate roll (image on the left), the fudge frosting (image in the middle) and the mountain cream icing (image on the right). Photo credit: Ariane Gauthier.

I decided to begin with the snow whirl chocolate roll as it required time to cool down, during which time I would work on the frosting and icing. The first step was sifting all dry ingredients thrice. After, I separated the egg yolks and whites, whipping the whites into soft peaks. Here’s where I went a little rogue: rather than fold the sugar into the egg whites after whipping, I incorporated it during whipping, as this helps to give them more volume.

I carefully cracked all four eggs and used the eggshells to separate the egg yolks from the egg whites. Once this was done, I used an electric beater to whip the egg whites with the sugar until it formed soft peaks. Photo credit: Dylan Roy.

I then made a little mistake: I mixed the egg yolks and vanilla with the dry ingredients rather than the egg white mixture. This ultimately negated the sifting of the dry ingredients, but here’s how I fixed it: I added about half of the egg white mixture and mixed it all together vigorously until no clumps remained. What this effectively did was somewhat defeat the whole point of whipping the egg whites, which was to have an airy and light cake mixture. However, since I only used some of the egg white mixture, I was able to gently fold in what remained and maintain some of the lightness I had previously built.

Negating the whole point of sifting the dry ingredients by prematurely mixing in some of the wet ingredients. The steps in order from left to right of how I mixed the dry and wet ingredients together. The last two images show how I salvaged the mix: I used half of the egg white mixture and vigorously mixed it with the dry ingredients until no clumps remained, and then I gently folded in what remained. Photo credit: Ariane Gauthier.

Once this step is done, a cooking sheet with edges is required to cook the cake. This may appear a little thin at first, but you must remember that the cake will eventually be rolled. And so off it went into a 400 ⁰F oven for 13 minutes. Now, it was time for filling and garnish!

Every vintage cooking recipe is a new experience where I’ve at least done one thing I’ve never done before. In this case, I’d never used a candy thermometer, despite owning one for many years. It’s complex and stressful, but in times like these it’s best to just trust the process and believe that Canadian Sugar Factories knew what it was doing in the 1930s!

Using a candy thermometer to make mountain cream icing and fudge frosting. The candy thermometer had to be held in both instances as the end could not touch the bottom of the pan; otherwise, it would provide a false reading of the temperature. In both cases, the steam produced by both mixtures obscured the reading of the thermometer, making what was already a difficult step even harder. Photo credit: Dylan Roy.

I regret to say that I didn’t do great with the mountain cream icing. I’m unsure whether I pulled it from the heat too early or if I simply let too much water evaporate, but I was ultimately left with a dry and crumbly icing that did not spread well. However, it did taste fairly good on its own.

Comparatively, the fudge frosting fared much better, as I had learned from my mistakes. Though I admit to having been unpleasantly surprised with two unlisted ingredients: butter and vanilla. I advise that any who attempt this recipe have both measured and on hand.

Thirteen minutes later, the cake sheet was ready. Here, again, I must admit to having strayed from the instructions. I’ve made Yule logs before for the holidays and the instructions are very clear: immediately roll the cake sheet tightly in a clean dish cloth sprinkled with powdered sugar and wait for it to cool. Do not add your frosting immediately as the heat of the cake will cause it to melt. You will be left with a gooey mess! I heeded my previous experience and waited for the cake to cool down before frosting.

Cake rolling and cake frosting. Rolling the cake is easier than one might think; the challenge is knowing how long to let it cool down. While I let it get a tad too dry, the beauty of frosting is that it hides the cracks! Photo credit: Dylan Roy.

The trick with these kinds of cakes is that they have to cool enough to not melt the icing but not so much that they dry out. Unfortunately for me, I waited a little too long, and the cake cracked when I unrolled it. I was able to smear some icing to patch the cracks and was fortunately able to cover the rest up with the fudge frosting. As we say in French: ni vu, ni connu (literally: unseen, unknown)!

Cross-section of the snow whirl chocolate roll cake. As you can see, I didn’t quite have enough icing to fill out the inside completely. Photo credit: Ariane Gauthier.

What do you think?

The cake, icing and frosting were delicious! I brought it into the office and my colleagues were pleasantly surprised. Everyone was more or less in agreement that the best part was the fudge frosting—it could almost have been a dessert on its own!

If you try this recipe, please share pictures of your results with us using the hashtag #CookingWithLAC and tagging our social media: Facebook, Instagram, X (Twitter), YouTube, Flickr and LinkedIn.

For more content on historical cooking, please consider the following links:

- A pumpkin pie from 1840 by Ariane Gauthier

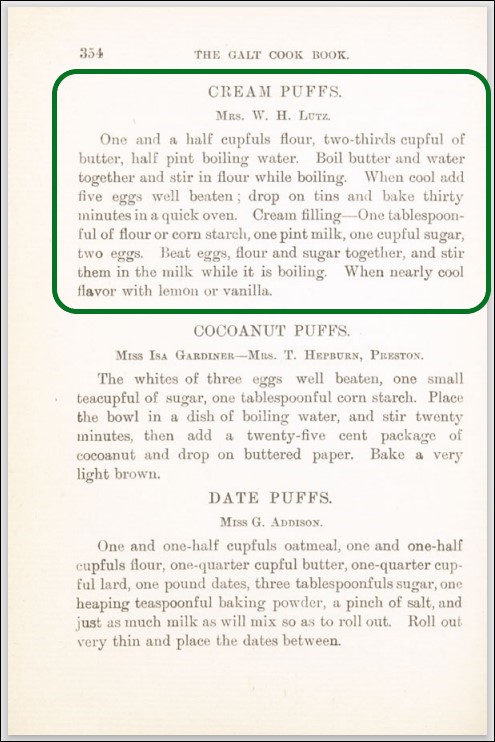

- Cream puffs from 1898 by Ariane Gauthier

- Dutch Apple Cake from 1943 by Ariane Gauthier

- Cheese and walnut loaf from 1924 by Ariane Gauthier

- Sweet Potato Pie: A Timeless Delight from 1909 to Today! by Dylan Roy

- Chocolate Cake from 1961 by Rebecca Murray

- Potato Biscuits from 1917: How the Housekeeper May Help to Save the Country’s Wheat Supply by Ariane Gauthier

- Jellied Vegetable Salad: Less is More! by Rebecca Murray

Ariane Gauthier is a Reference Archivist in the Access and Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.