Canada joined the First World War on August 4, 1914, alongside Great Britain and the rest of the British Empire. What began as a mobile war quickly turned into a static one, with the entrenchment of the Allied and Entente armies. By 1915, the momentum that had previously animated early fighting had vanished, leading to a grueling war of attrition in the trenches across Europe and the Mediterranean.

The devastation of Europe’s countryside reduced accessible food supplies, a situation that was made worse by the arrival of unprecedented numbers of soldiers mobilized from all corners of the world. Great Britain was quick to marshal the resources of its empire, hoping to fuel its war effort. Canada contributed by supporting troops overseas through its agricultural and industrial output, but it wasn’t enough. Soon, all levels of government had to consider other means of bolstering aid, ultimately settling on rationing key resources.

By the third year of the war, wheat was becoming scarce. Anticipating a ration order, the Ontario Department of Agriculture published the pamphlet “War Breads: How the Housekeeper May Help to Save the Country’s Wheat Supply” in August 1917, claiming that “every pound of flour saved means more bread for the army.” However, it admitted that its suggested wheat flour substitutes wouldn’t necessarily yield tasty breads or biscuits: “The constant use of these coarser breads might not agree with some people, but as a rule they will be found more healthful than the finer white bread.”

Cover of the pamphlet “War Breads: How the Housekeeper May Help to Save the Country’s Wheat Supply” (OCLC 1007482104).

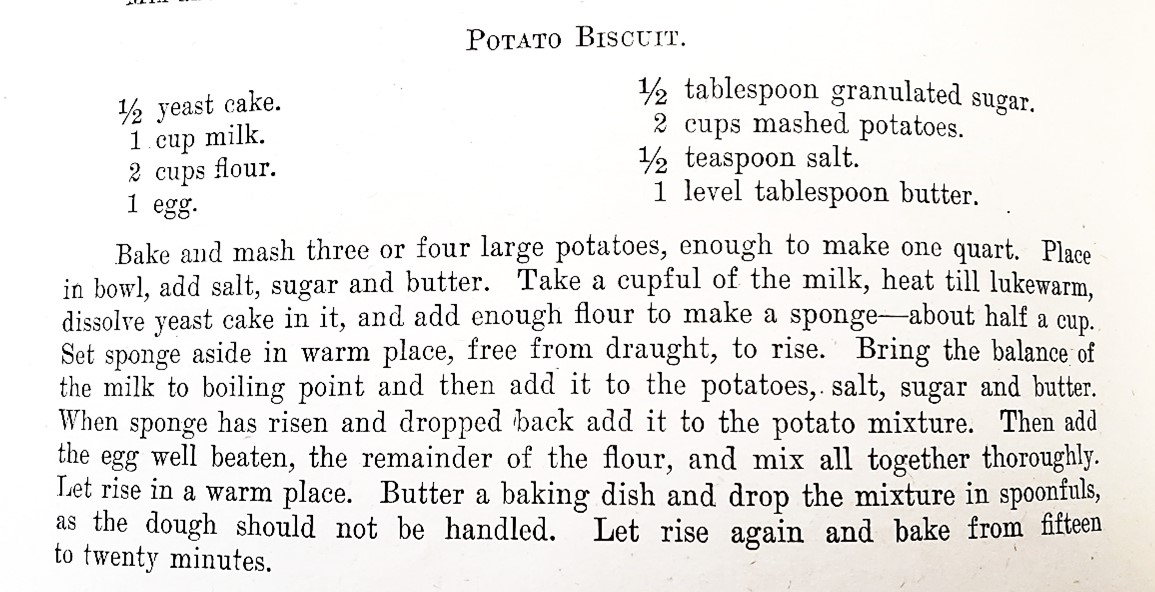

Intrigued by this unique pamphlet, I chose a recipe that might give me a taste of a housekeeper’s patriotic efforts: potato biscuits. Having enjoyed potato breads and donuts before, I felt hopeful.

Recipe for potato biscuits from the pamphlet “War Breads: How the Housekeeper May Help to Save the Country’s Wheat Supply” (OCLC 1007482104).

I only glanced at the recipe’s ingredients initially. They seemed adequate, but as I started assembling the potato biscuits, the meager half tablespoon of granulated sugar and single tablespoon of butter made it clear that these biscuits might end up bland or very yeasty. Given the war-era context, this wasn’t entirely surprising—wheat flour wasn’t the only ingredient being rationed.

First, I assembled my ingredients. Strangely, the recipe called for baking the potatoes instead of boiling them. Perhaps this was to control the moisture content. I heated the oven to 400°F and baked the potatoes for 45 minutes to an hour until they were fork-tender.

While the potatoes baked, I prepared the yeast mix. Unable to find cake yeast, I used bread yeast instead. I mixed lukewarm milk with the yeast and some flour, setting it aside until it bubbled and rose.

Yeast, flour and milk mix. Notice the myriad of bubbles produced by the yeast as it froths. Photographer: Ariane Gauthier.

I mashed the potatoes and mixed them with salt, sugar, butter, and boiling milk until smooth. I added the yeast mixture, the egg, and the remaining flour. By this point, the oven had cooled slightly, making it an ideal spot to let the dough rest and rise.

Making the potato biscuit dough. I vigorously mixed the ingredients at every step to ensure everything was as uniform as possible. Photographer: Ariane Gauthier.

The dough was gloopy, much to my surprise. With such little liquid compared to the dry ingredients, I hadn’t expected this. Taking the recipe’s warning to heart, I avoided handling the dough and used spoons to scoop it into a buttered muffin tin.

The dough mixture before and after rising for a few hours in a warm place. As the recipe indicated, it was very gloopy and could not be handled by hand. Photographer: Ariane Gauthier.

As seems to be the custom with these old recipes, the recipe didn’t specify the oven temperature for baking, so I settled on 400°F and watched closely as the potato biscuits baked for 15 to 20 minutes until golden.

The completed potato biscuits. The one on the left has been garnished with jam. I decided to add berries to another on the right before baking. Photographer: Ariane Gauthier.

And voilà! What do you think?

The strong yeast smell hit me as soon as I pulled the biscuits from the oven. As for the flavour? Shockingly bland. Luckily, I had some traditional strawberry jam on hand, which saved the day (thanks mom and dad!). These potato biscuits were better as a jam vehicle than a standalone treat.

As per my tradition, I took the biscuits to work and offered them to my colleagues. Never have I made such polarizing food! They either loved it or hated it; no one was neutral. So, if you’re feeling adventurous or just want a taste of history, give these potato biscuits a try—and don’t forget the jam!

If you try this recipe, please share pictures of your results with us using the hashtag #CookingWithLAC and tagging our social media: Facebook, Instagram, X (Twitter), YouTube, Flickr and LinkedIn.

Additional resources:

- In the same series, on Library and Archives Canada’s blog:

- A pumpkin pie from 1840 by Ariane Gauthier

- Cream puffs from 1898 by Ariane Gauthier

- Dutch Apple Cake from 1943 by Ariane Gauthier

- Cheese and walnut loaf from 1924 by Ariane Gauthier

- Sweet Potato Pie: A Timeless Delight from 1909 to Today! by Dylan Roy

- Chocolate Cake from 1961 by Rebecca Murray

- Twelve Days of Vintage Cooking, YouTube channel, Library and Archives Canada

- Sifting through LAC’s Cookbook Collection, podcast episode, Library and Archives Canada

Ariane Gauthier is a reference archivist with the Access and Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

![Cover page of a booklet with the inscription "Mangeons du fromage : Recettes et menus" [Translation: Cheese Recipes for Every Day].](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/image-1.jpg?w=584&h=863)