By Stacey Zembrzycki

This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic, and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

Stanley Grizzle was born in Toronto in 1918, to parents who had immigrated separately from Jamaica in 1911. His mother laboured as a domestic servant while his father found work as a chef with the Grand Trunk Railway (Grizzle, My Name’s Not George, p. 31). The eldest of seven children, Grizzle became a porter for the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) at the age of 22, pulled away from school to help his parents meet their dire financial obligations. “Porters,” as he puts it in his memoir My Name’s Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in Canada, “were well respected, and looked up to by many in the community because they had steady employment. In essence, they were the aristocrats of African-Canadian communities. They were the most eligible bachelors and parents often encouraged their daughters to marry a porter” (p. 37).

Book cover of My Name’s Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in Canada: Personal Reminiscences of Stanley G. Grizzle (OCLC 1036052571). Image courtesy of the author, Stacey Zembrzycki.

Grizzle’s early life began to follow this well-established trajectory, especially since portering was one of the only employment options available to Black men in the mid-twentieth century, until it was interrupted by the realities of the Second World War. Conscripted into the Canadian Army in 1942—legislation he firmly opposed throughout his life—Grizzle spent an extended amount of time away from the family he had only just started. In fact, his first child, Patricia, arrived on the very day he departed for Europe and did not have the opportunity to meet her father until he returned home, when she was three years old (Grizzle, My Name’s Not George, p. 57).

Grizzle’s early experiences with poverty, and the racism he encountered as a porter and a soldier, went on to dictate the new career path he paved for himself. First, as a celebrated labour union activist with the Toronto division of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), then as the first Black Canadian to be employed by the Ontario Ministry of Labour as a clerk with the Ontario Labour Relations Board, and later as the first Black Canadian to be appointed as a judge in the Court of Canadian Citizenship. There is no doubt that these experiences also informed the interviews he conducted in 1986 and 1987, now held by Library and Archives Canada (LAC).

As I mentioned in a previous blog, these 53 informal conversations among friends and acquaintances constituted what many, including Melvin Crump, referred to as “porter talk.” Meeting in Crump’s Calgary living room on November 1, 1987, the two men spent the afternoon discussing the intricacies of what it meant to be a porter. Not only did they describe what the job signified for them as Black men, they also explained how it shaped their identities and the larger Black communities that supported them.

Having been born in Edmonton in 1916 after his parents immigrated in 1911 as homesteaders from Clearview, Oklahoma, Crump’s early circumstances were much different from Grizzle’s. However, the men had both experienced the abject racism that was central to Black experience in Canada, which ultimately led them to a career with the CPR. Like Grizzle, Crump went to work for the company because it offered stable employment, away from the meatpacking plants and farms in the region that provided little stability and paid poor wages. In fact, Crump knew that this would be the only way to get ahead, so he lied about his age to obtain a job when he was just nineteen years old, thereby defying the age restriction that limited employment to those over twenty-one.

Like Grizzle, Crump spent about twenty years working for the CPR before seeking employment beyond the rails. The move from steam to diesel engines, coupled with automation, drastically changed the size, shape and appearance of this labour force, as well as passenger experience forever. As they had always done, the men moved toward a secure future. Regardless of their similar but divergent histories, both men prided themselves on having done their jobs well, and continued to stress the inherent value of unionization, regardless of the risks, nearly thirty years after leaving portering.

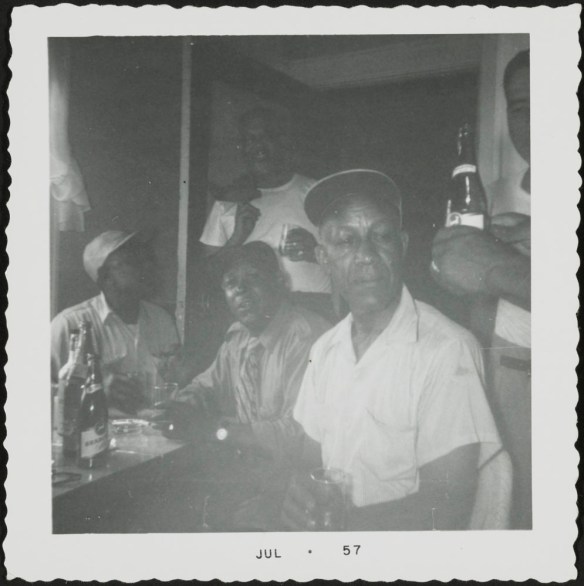

Melvin Crump on 8th Avenue, Calgary, Alberta, ca. 1940, (CU1117465).

Photograph: Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

There is a coded language to this conversation. It is implicit, organic and almost impossible to understand without having lived through the institutional racism and systemic segregationist policies that guided nearly every aspect of these men’s lives, on and off the rails (Mathieu, North of the Color Line). The conversation is warm, the laughter is heartfelt, and the experiences intersect in complex ways. There is no need for detailed explanations between the men. These conversations were meant to support the writing of Grizzle’s memoir. While he was committed to documenting and preserving the history of portering in Canada, one wonders if these conversations were meant to be heard by others. And yet, here we are, listening in, translating their meaning and breaking the coded nature of these exchanges nearly forty years later.

By pushing Crump to articulate the particular circumstances that defined his experiences in Calgary—the friendships that were made, nurtured and even broken there, the specifics of unionization within that branch and the role of the wider community in fighting for change and supporting porters and their families—Grizzle highlighted the similar ways in which porters across the country were bound together by this demanding and often degrading profession.

And yet these intersections, which we hear across the collection, quickly become more complex when Grizzle asks Crump, as he did with all interviewees, to recount memorable railroad anecdotes. Porter talk offers insight into how each man put one foot in front of the other and built a life around portering. We get brief but powerful glimpses of who these men were, how they saw the world and why they tolerated and overcame the abuse they endured daily. As we gain a superficial understanding of each man’s personality, we also hear about resilience. Stories about memorable passengers naturally shift to stories about the other Black men with whom they shared railcars and responsibilities. The sense of community among porters and the conversations that started on the trains and flowed over into these interviews are what make these recordings so special. The laughter, reinforced by years of hindsight, reflection, recognition of service and a job well done, fuels the jovial exchanges that lead us into the realm of porter talk.

When Grizzle asked Crump to tell him about the prominence of nicknames between porters, Crump let out a roaring laugh, declaring:

Oh nicknames used between porters? Oh-oh-oh-oh, yes. Yeah, I know what you mean. You mean porter talk? You mean porter talk? Well, uh, uh, some of the porter talk names I wouldn’t wanna mention on tape, because if I did uh, it would shock some of the readers or some of the listeners, but they had a language all of their own, I’ll tell you. And some of the conversations that they would get in between themselves. I couldn’t dare, I wouldn’t dare to start to-to mention none of those things. (Interview 417403, File 2 [22:33])

And yet, porter talk is exactly what he, and nearly all of Grizzle’s other interviewees, transmit on these recordings. He couldn’t dare and yet he does. We are offered a seat at the proverbial table to listen, learn and take in a world that no longer exists, and yet remains central to who we are as Canadians.

It is this passing reference that inspired Discover Library and Archives Canada’s new miniseries Porter Talk. This will be the first in a new podcast production entitled Voices Revealed, which will delve into the vast and rich oral history holdings at LAC. While porters have figured prominently in popular culture in recent years, this will be the first time that these men, along with their wives and children, will speak for themselves. It is not enough to write about their exceptional experiences. Readers must hear these narratives. They must be able to differentiate accents, listen to laughter alongside rage, pause to ponder the challenges of portering and the resilience of Black communities in Canada, and grasp the power in these men’s voices and the history they convey.

Grizzle, Crump and all those who graciously agreed to be interviewed, will guide us through this history on their own terms, revealing why it is imperative for us to keep listening, to keep remembering, and to keep porter talk alive, especially as we continue to navigate the many challenges posed by institutional and systemic racism and discrimination in this country and beyond. The structures that these men, alongside their wives and children, worked so hard to dismantle, continue to matter. These voices remind us of the work that remains to be done.

To listen to this miniseries, you can subscribe to Discover Library and Archives Canada for free wherever you get your podcasts.

Additional resources

- My Name’s Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in Canada, Personal Reminiscences of Stanley Grizzle, by Stanley G. Grizzle with John Cooper (OCLC 1036052571)

- North of the Color Line: Migration and Black Resistance in Canada, 1870–1955, by Sarah-Jane Mathieu (OCLC 607975641)

- They Call Me George: The Untold Story of Black Train Porters and the Birth of Modern Canada, by Cecil Foster (OCLC 1080209154)

- Black porters’ voices and stories: the Stanley Grizzle interview collection, by Stacey Zembrzycki, Library and Archives Canada Blog

- The Ladies’ Auxiliary of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, by Stacey Zembrzycki, Library and Archives Canada Blog

- Soundscapes of the Stanley Grizzle Interview Collection, by Stacey Zembrzycki, Library and Archives Canada Blog

Stacey Zembrzycki is an award-winning oral and public historian of immigrant, ethnic, and refugee experiences. She is currently employed as a Podcast Development Specialist in the Outreach and Engagement Branch at Library and Archives Canada.