By Sali Lafrenie

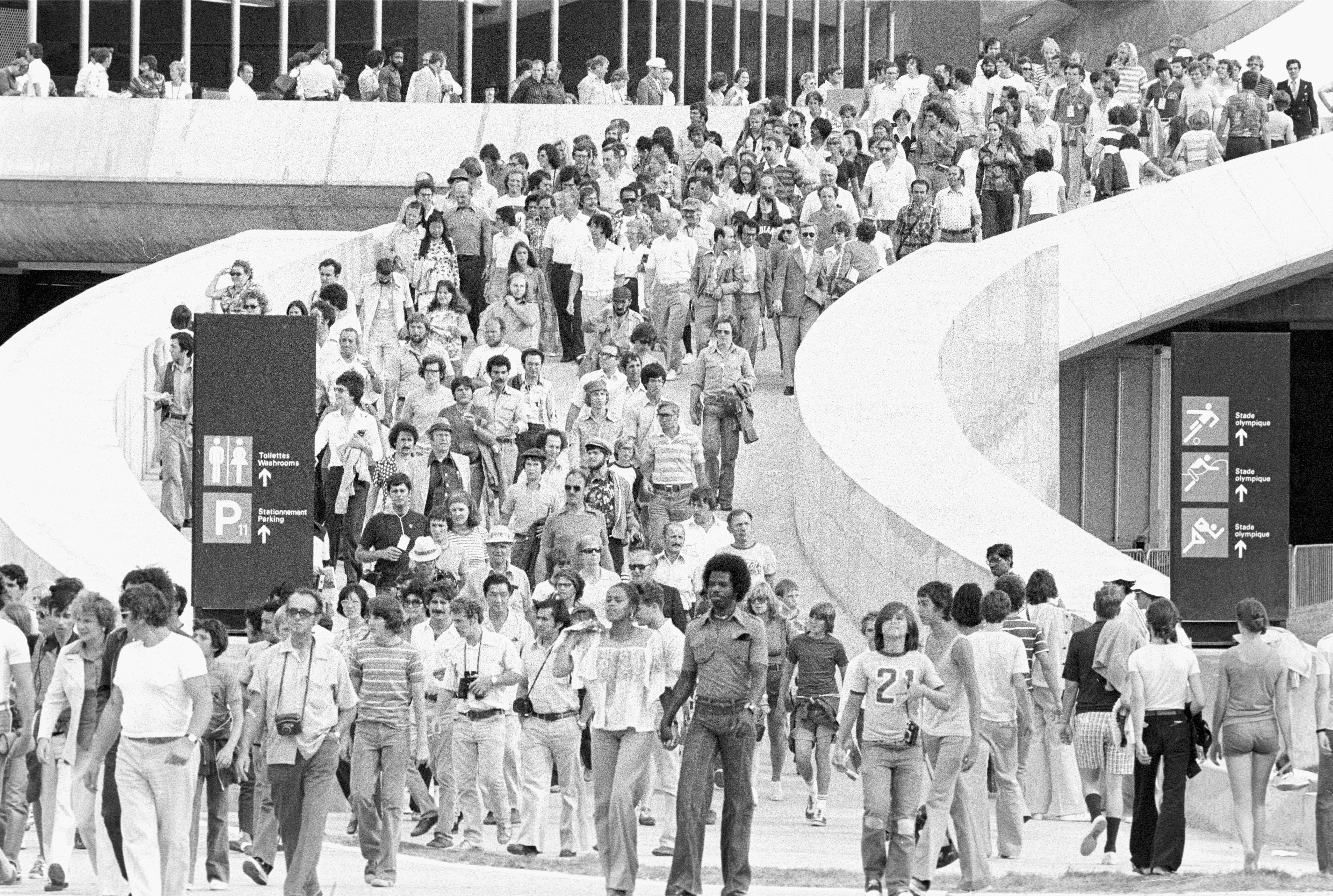

With the Olympic Games winding down and the Paralympic Games winding up in 2 weeks, it’s time for a paralympic preview. The 2024 Paralympics will also take place in Paris, from August 28th to September 8th, and will include 22 sports:

- Para archery

- Para athletics

- Para badminton

- Blind football

- Boccia (similar to bocce and pétanque)

- Para canoe

- Para cycling

- Para equestrian

- Goalball

- Para judo

- Para powerlifting

- Para rowing

- Shooting Para Sport

- Sitting volleyball

- Para swimming

- Para table tennis

- Para taekwondo

- Para triathlon

- Wheelchair basketball

- Wheelchair fencing

- Wheelchair rugby (previously called murderball)

- Wheelchair tennis

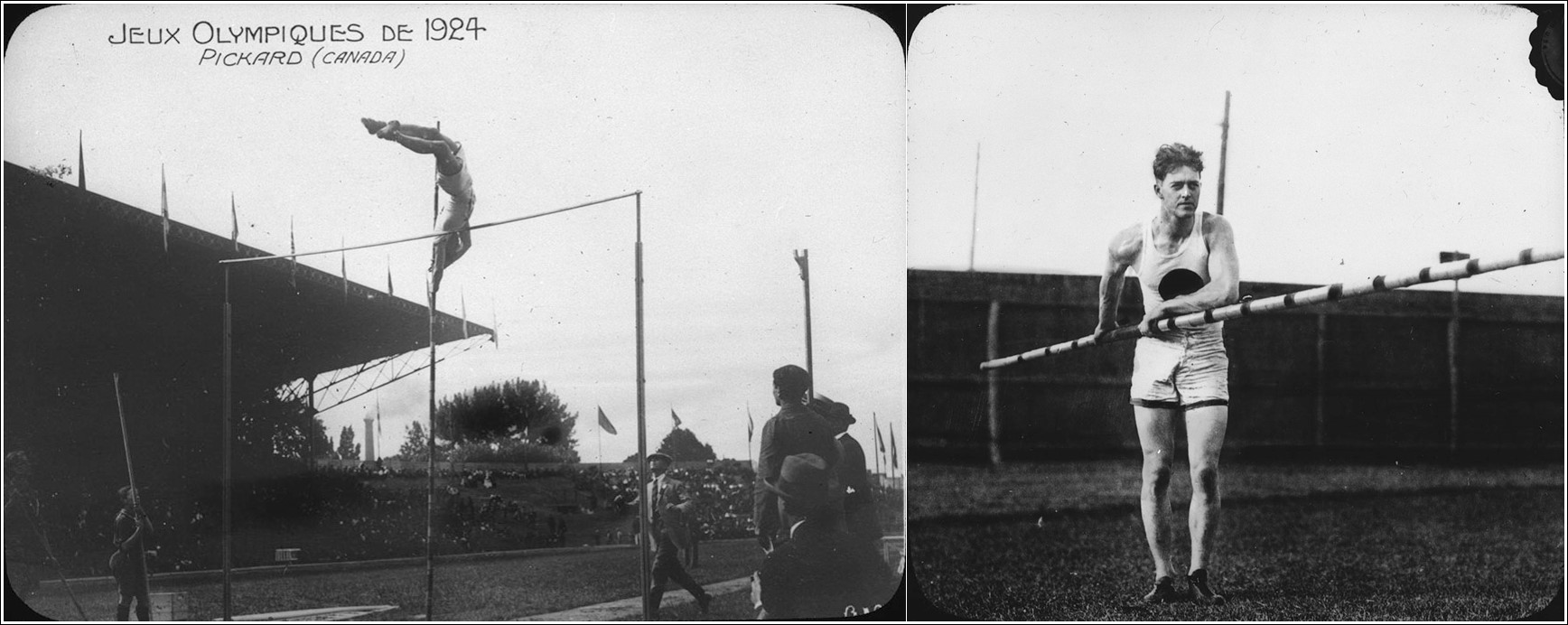

While the Modern Olympic Games date back to 1896, the Paralympics have a different history. The Paralympic Games as we know them date back to 1984. But they had a different name from 1960 to 1980: the International Stoke Mandeville Games.

The International Stoke Mandeville Games

Although the International Stoke Mandeville Games began in 1960, their origin dates to 1948 at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital in England. Like the Inter-Allied Games and the Invictus Games, the Stoke Mandeville Games were meant to be a rehabilitative experience for people with disabilities and for veterans. The Games eventually grew into a large-scale sports competition.

Initially consisting of only wheelchair athletes, the Games grew over time to include athletes from other countries—making them international—as well as athletes with a range of disabilities, which lead to the inclusion of more sports.

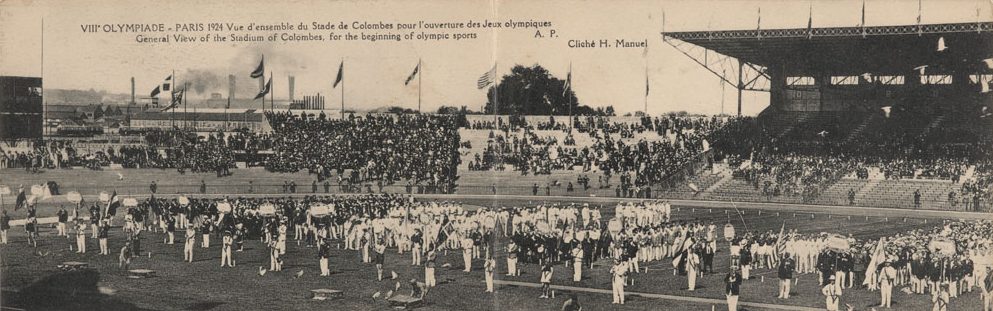

While the International Stoke Mandeville Games are considered the precursor to the Paralympics, there are and were many different types of sports competitions for athletes with disabilities such as the World Abilitysport Games, the Special Olympics, the Parapan American Games, and the Deaflympics (first held in Paris in 1924).

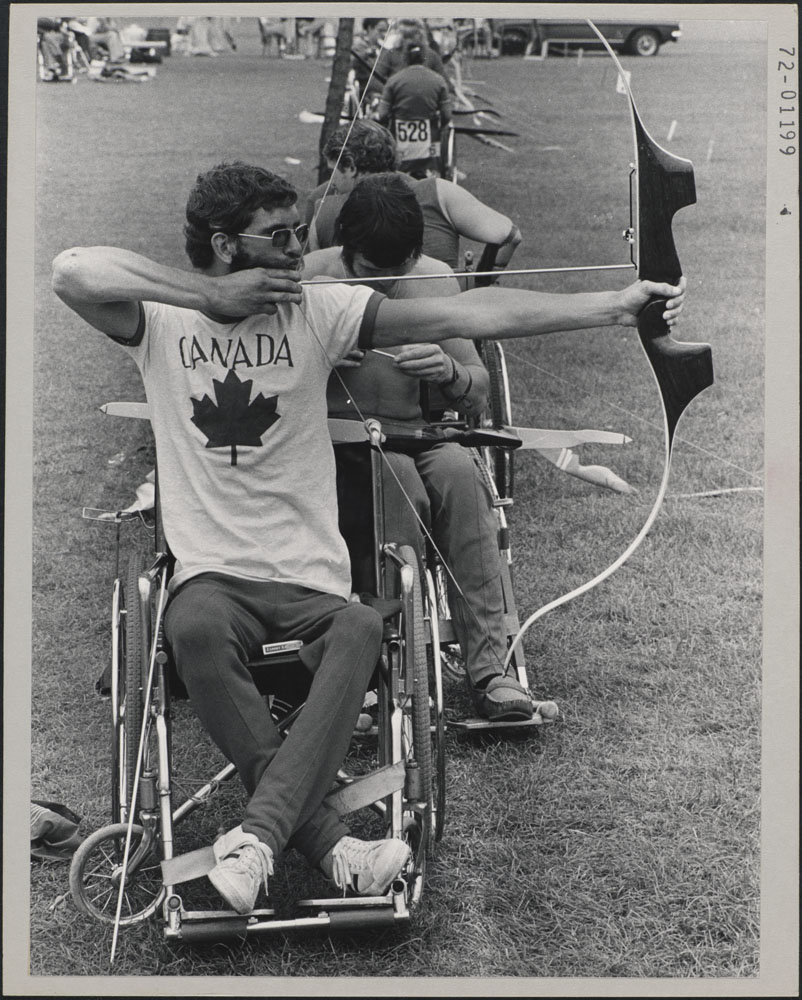

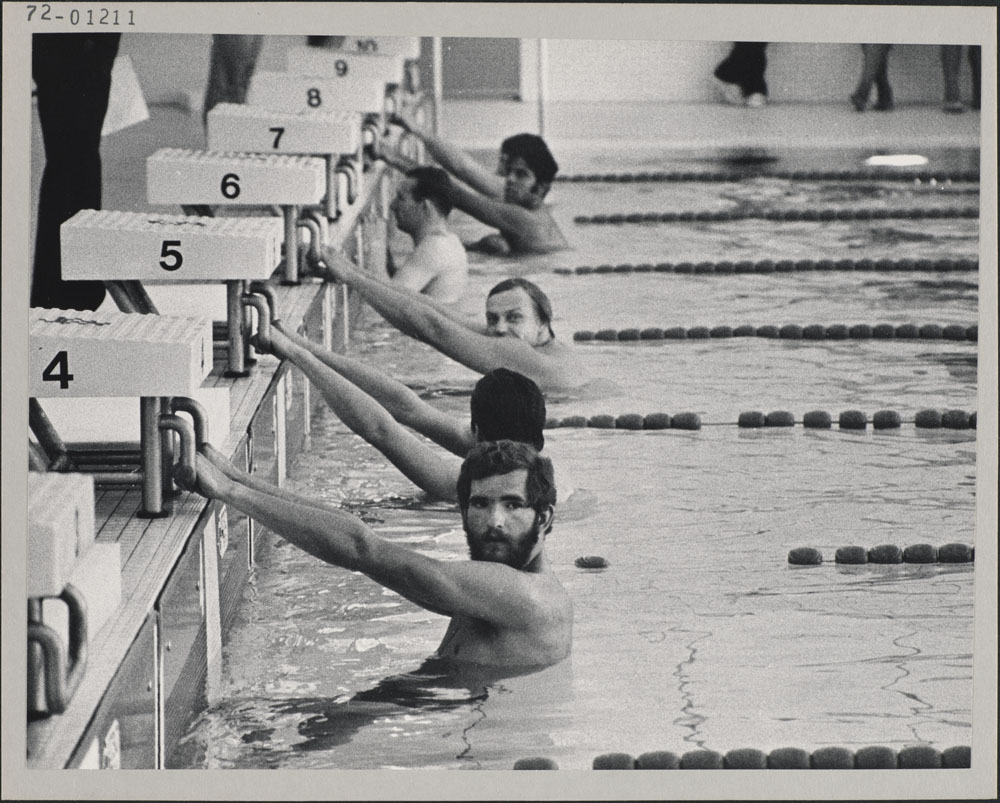

Below, we can see photographs of athletes competing at the 1972 International Stoke Mandeville Games in sports like archery, swimming, and wheelchair basketball.

Archery, 21st International Stoke Mandeville Games, Heidelberg, Germany, August 1–10, 1972. (e011783300)

Swimming, 21st International Stoke Mandeville Games, Heidelberg, Germany, August 1–10, 1972. (e011783302)

Basketball, 21st International Stoke Mandeville Games, Heidelberg, Germany, August 1–10, 1972. (e011783301)

Canada and the Paralympic Games

Participating in the Games for over 50 years, Canadian Para athletes have a long and shiny history at the Paralympics. It’s safe to say that Canadian Para athletes tend to win a lot, given that they rank fourth in All-Time Paralympic Summer Games Medal Standings. Team Canada has dominating records in Para swimming, Para athletics, Para cycling, and wheelchair basketball. Notable athletes in these sports include Benoît Huot, Michelle Stilwell, Chantal Petitclerc, and Richard Peter.

Each of these athletes have made their mark on parasport history in different ways. Huot did so at Rio 2016 when he earned his 20th Paralympic medal, officially tying the record for second all-time Paralympic swimming medals. Stilwell left her mark in two different sports, wheelchair basketball and wheelchair racing, winning at least one gold medal in both sports. Senator Chantal Petitclerc, perhaps one of the most recognizable names in Canadian parasport alongside Rick Hansen, represented Canada at 5 Paralympics and won 21 medals. Richard Peter, also a dual-sport athlete and five-time Paralympian, competed in wheelchair basketball and in Para badminton, winning multiple medals with the wheelchair basketball team throughout his career. Peter was also featured in the docuseries “Chiefs and Champions” highlighting Indigenous athletes representing Canada in sports.

Paralympic athlete Benoît Huot during recognition ceremony at Parliament Hill with Prime Minister Stephen Harper. Credit: Jason Ransom. (MIKAN 5586583)

Paralympic athletes Michelle Stilwell and Jason Crone during recognition ceremony at Parliament Hill with Prime Minister Stephen Harper. Credit: Jill Thompson. (MIKAN 5609841)

Paralympic athletes Tyler Miller, Marco Dispaltro, and Richard Peter during recognition ceremony at Parliament Hill with Prime Minister Stephen Harper. Credit: Jason Ransom. (MIKAN 5609841)

The Canadian Paralympic Hall of Fame

Canadians have made an impact on the Games inside and outside of the competition itself. Currently, the Canadian Paralympic Hall of Fame consists of 42 inductees in three categories: builders, coaches, and athletes.

One important builder is Dr. Robert W. Jackson, an orthopaedic surgeon who is credited with founding the Canadian Wheelchair Sports Association and as being a major advocate of parasports. While Dr. Jackson’s legacy lies in his contributions to the medical field as a pioneer of arthroscopic surgery, his legacy is also important to the world of sports. Outside of his work promoting parasports, Dr. Jackson also worked with professional athletes in two major leagues: the Canadian Football League (Toronto Argonauts) and the National Basketball Association (Dallas Mavericks). And in 1976, he was responsible for organizing the Paralympics in Toronto, also known as the Toronto Olympiad. All of this and more can be found in Dr. Jackson’s fonds here at LAC.

Another important Hall of Fame inductee is Eugene Reimer, a member of the first Canadian Paralympic team and a dominant wheelchair athlete. Throughout his athletic career, Reimer won 10 medals across 4 Paralympics and more than 50 medals at national and international competitions. He was also named Canadian male athlete of the year for these achievements. Reimer was an all-around athlete, a true competitor and multi-talented athlete who also played for the Vancouver Cable Cars wheelchair basketball team—the same team that Rick Hansen and Terry Fox played on in British Columbia. Check out this photo of Reimer competing in Para archery at the 1972 Games.

Canada’s Eugene Reimer, archery, 21st International Stoke Mandeville Games, Heidelberg, Germany, August 1–10, 1972. (e011783299)

Athletes and sports to watch

Turning back to Paris 2024, let’s look at some of the athletes and sports coming up!

Given Canada’s success in Para swimming, it only makes sense to start there. This year, Canada is sending 22 Para swimmers to Paris. While there are some new faces, there are quite a few familiar ones including Aurélie Rivard, Nicholas Bennett, and Katarina Roxon, who will be competing in her fifth Paralympics.

While there are a lot of crossover sports between the Olympic and the Paralympic Games, one of the best parts of the Paralympics are the sports that are unique to them, like goalball. If you’ve never watched the sport, then you’re in for an exciting time, and if you have watched goalball, then you know exactly what I mean. The women’s goalball team has seen a lot of success recently and historically, securing their spot in Paris by winning gold at the 2023 Parapan American Games.

Just like the Olympics, the Paralympics are always evolving and changing. Sometimes that evolution looks like adding or removing sports, and other times it looks like providing more parity between athletes and prize money. In the last 16 years, the Paralympics have added five sports to their roster: Para rowing, Para triathlon, Para canoe, Para badminton, and Para taekwondo. It’s an exciting time to be a sports fan, and if you can’t get enough of the Paralympic Games and want to learn more, check out this list of 50 Things To Know About The Paralympic Games. Happy watching!

Additional Resources

- 2012-09-19 Olympians, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN 5609841)

- 2015-07-10 Toronto Pan American Games, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN 5610897)

- Amazing athletes: an all-star look at Canada’s Paralympians by Marie-Claude Ouellet and Jacques Goldstyn; translated by Phyllis Aronoff and Howard Scott (OCLC 1240172154)

Sali Lafrenie is a Portfolio Archivist in the Private Archives Branch at Library and Archives Canada.