By Brittany Long

The 1960s and 1970s were marked by global turbulence, with terrorist attacks, airplane hijackings, and kidnappings frequently dominating the headlines. Against this backdrop of uncertainty, preparing the security for the 1976 Olympic Games in Montréal posed a monumental challenge for Canadian security agencies. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), the Canadian Armed Forces, and local authorities had to coordinate their efforts to ensure the safety of athletes and spectators from around the world.

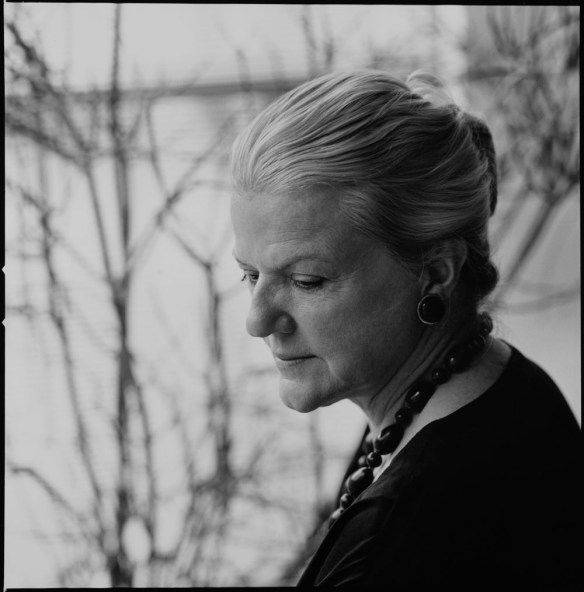

Opening ceremony at the Montréal Olympic Games, July 17, 1976. Photo: Paul Taillefer. (e004923376)

Not only was Queen Elizabeth II set to visit and officially open the Games, but Montréal was set to host 6,084 Olympic athletes from 92 different countries. Given the scale of the event, no one wanted a repeat of the tragic events at the 1972 Munich Olympics, where 11 athletes were killed in a terrorist attack.

With the 1976 Summer Olympics taking place during the Cold War, it was crucial to assess possible threats, identify areas of vulnerability, and ensure the security of all venues. Security measures needed to be meticulously planned and kept confidential in the lead-up to and during the Games to protect Canadians, foreign visitors, and athletes. For instance, intensive security plans were required for something as simple as Queen Elizabeth II’s route from her lodging to the venue.

Preparation began months before the event, during which the alert level was at its peak, particularly for departments such as External Affairs, the RCMP, and National Defence. All of the agencies and federal departments involved generated a large legacy of records, which were created in order to maintain the security surrounding the Olympic Games.

Eventually, some of these documents were transferred to Library and Archives Canada (LAC). For example, the Department of External Affairs fonds holds at minimum nine boxes worth of material related to the 1976 Games, while the RCMP fonds holds approximately 170 boxes. Additional records are scattered throughout various other fonds as well.

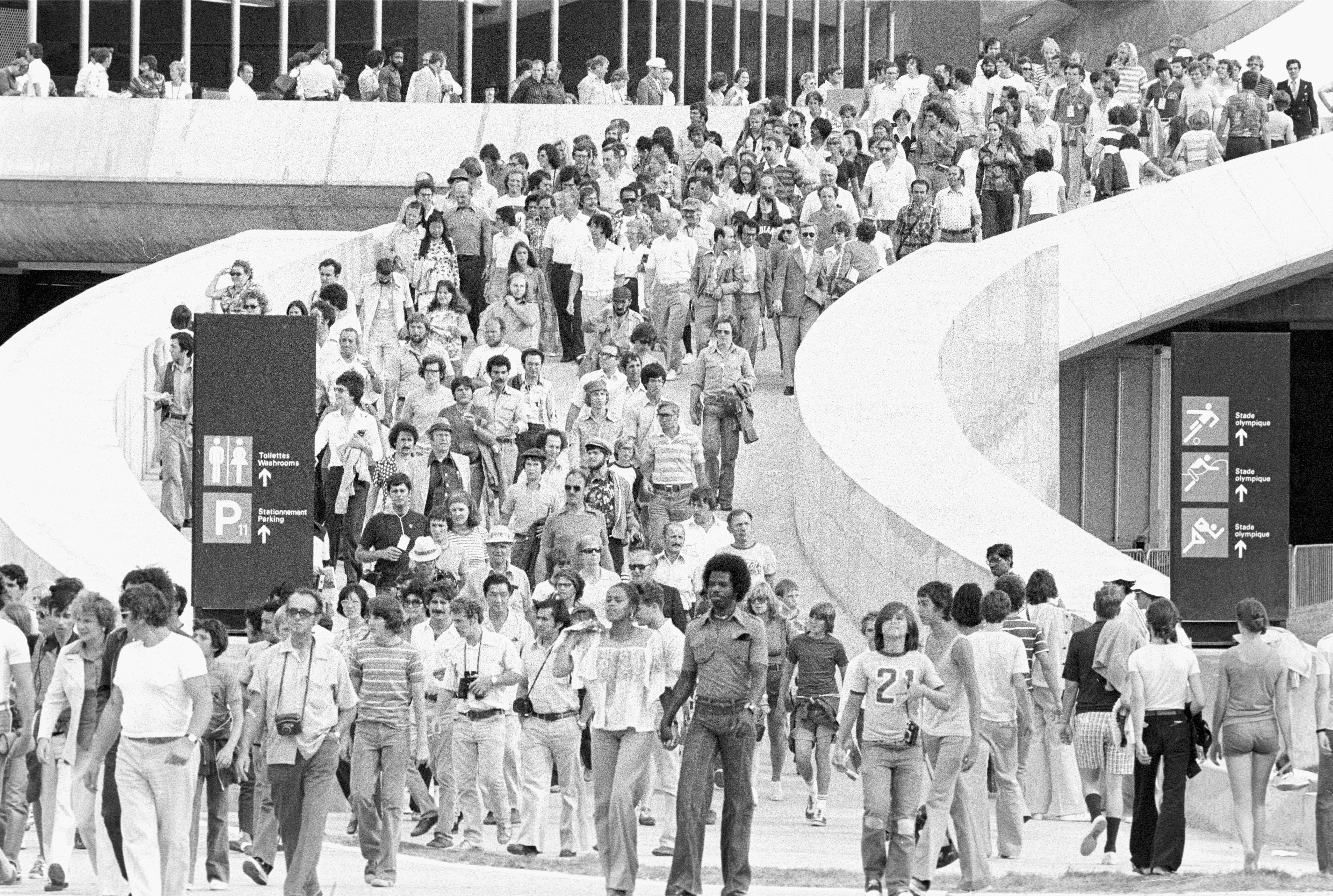

Crowds walking down a stadium ramp at the 1976 Montréal Olympics Games. Photo: Paul Taillefer. (e004923378)

Since the documents pertained to security matters, most were classified as confidential, secret, and at times top secret upon their creation and remained classified when transferred to LAC. Many of these documents are still classified almost 50 years after the closing ceremonies of the 1976 Olympics. This creates delays in granting access to these records. Even worse, there is no way to know exactly which records are classified. How is this possible?

Decades ago, recordkeeping and transfer protocols differed significantly. File lists of documents transferred to LAC often lacked any indication of their security classification. As a result, to determine if the Montréal Olympic records remain classified, we first need to identify what we have in our collections about the Games. Once identified, we then need to review the documents to ascertain their classification status—a time-consuming process.

Over the summer and early fall of 2023, we focused on nine boxes of material from the Montréal Olympic Games series in the Department of External Affairs fonds—a relatively small selection of records compared to other series in LAC’s collections. It took days to sift through and analyze the contents of these boxes to determine how much of it remained classified. This review determined that around a third of the files within this one series are still classified.

Closing ceremony at the Montréal Olympic Games featuring 500 young women dancing while a male streaker poses among them, August 1, 1976. Photo: Paul Taillefer. (e004923381)

After examining the contents of the boxes and information within the files, an analytical report was compiled. According to the fundamental principle of declassification, only the creator of the records can declassify them. Consequently, the results of our analysis were submitted to the relevant departments for their decision.

The classified records related to the security measures for the 1976 Montréal Olympic Games are not the only ones that remain classified decades after their creation. The declassification section of the Access to Information and Privacy Branch at LAC works closely with other departments to enhance access to historical records for all Canadians. This collaboration aims to unlock more of our collective past and ensure that valuable historical information is accessible to the public.

Additional Resources

- “How security at the 1976 Montréal Summer Games set a precedent for future Olympics” by Dominique Clément

- “The Transformation of Security Planning for the Olympics: the 1976 Montreal Games” by Dominique Clément

- Games of the XXI Olympiad, Montréal 1976, Library and Archives Canada Co-Lab challenge

Brittany Long is an archivist working on declassification in the Access to Information and Privacy Branch at Library and Archives Canada.