By Stacey Zembrzycki

This four-part Black Porter Perspectives blog series is inspired by a striking and haunting set of images found within the Department of National Defence (DND) accession 1967-052. These photographs provide a window into service to country through various vantage points during and after the Second World War, revealing the intersections of class, race and duty.

Princess Alexandra represents the British Crown on Canadian soil during her Royal Tour in 1954. (e011871943)

Volunteer, and in some cases, conscripted servicemen departing for and returning from battle offer us a glimpse into the realities of preparing for war, deploying to distant fronts, and returning home again.

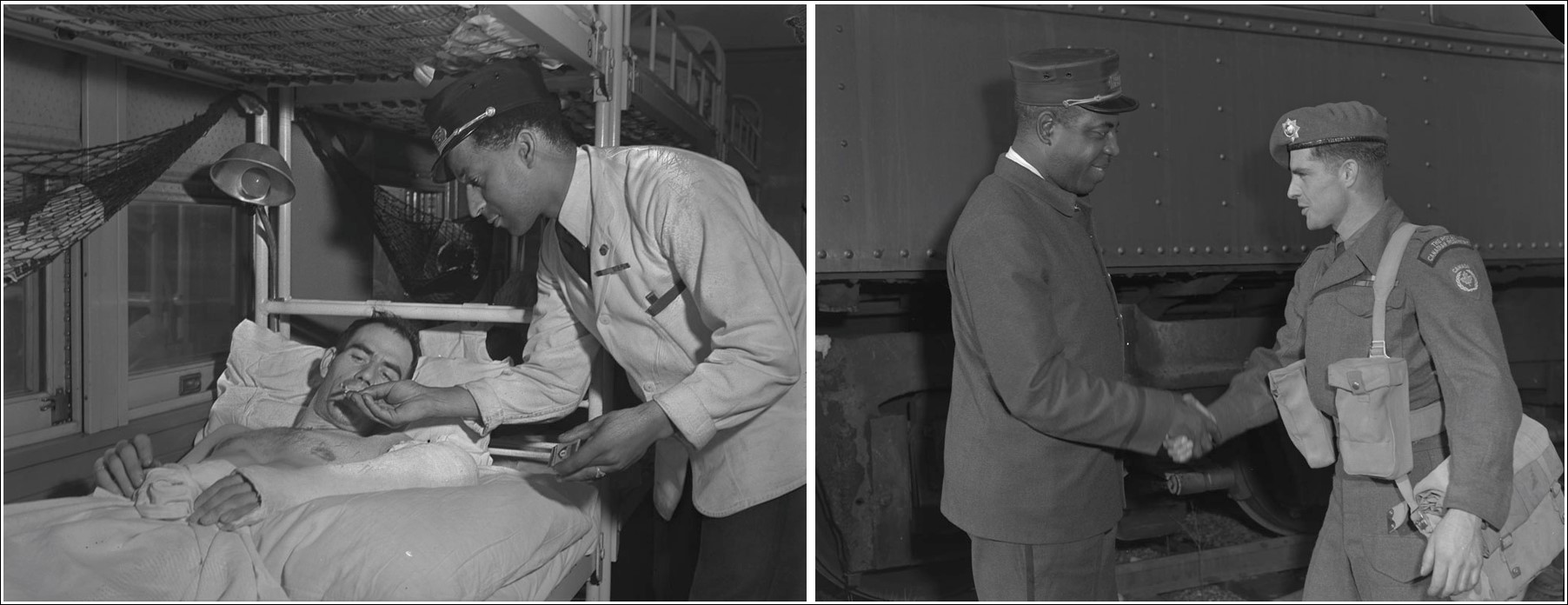

Image on left: A sleeping car porter and an injured soldier on the Lady Nelson hospital train. Image on right: Porter Jim Jones of Calgary shakes hands with Private Harry Adams, a Halifax member of the Royal Canadian Regiment, as Canadian Army Special Force units arrive at Fort Lewis, Washington, for brigade-strength training. (e011871940 and e011871942)

Black men, often identified as train staff in the image descriptions, appear in every photograph—serving as the unifying thread in these historical moments. Their essential work, whether as cooks or sleeping car porters, made train travel possible, luxurious even, in times of war and peace. While this labour has often been silenced and overlooked in our national narratives, it is undeniably present in these images.

How can we begin to piece together the experiences that are captured in these images? One way is to turn to the Stanley G. Grizzle collection, particularly the interviews he conducted in 1986 and 1987 with former Canadian National (CN) and Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) sleeping car porters. Grizzle sought to document the exploitative company culture Black men endured up to the mid-twentieth century and the long and complex struggle that ultimately led to their unionization. At the same time, he also made space for his narrators to recount memorable stories from their time on the rails. These recollections, if listened to closely, allow us to begin piecing together a narrative that enables us to better contextualize some of these DND images. Like the past, however, these moments remain fleeting and fragmentary, with much lost to history.

Five interview clips from Grizzle’s collection provide insight into what portering looked like during the Second World War. While these exchanges provide few details about the images above, they offer glimpses into porters’ working conditions and the added responsibilities they shouldered during wartime. Let’s listen to what these conversational tangents reveal about their experiences:

You can read the transcript from this sound clip here. (ISN 417383, File 1, 34:30)

You can read the transcript from this sound clip here. (ISN 417397, File 2, 9:26)

You can read the transcript from this sound clip here. (ISN 417379, File 1, 17:18)

You can read the transcript from this sound clip here. (ISN 417379, File 1, 5:56)

You can read the transcript from this sound clip here. (ISN 417386, File 1, 32:12)

The experiences of the men, the people they served, and their feelings about the additional duties thrust upon them as a result of the Second World War offer valuable insights that help humanize the role of portering. For George Forray, the demands of wartime rail service provided financial security, allowing him—and many others—to secure full-time employment during this turbulent period. Bill Overton, while recounting the hard-fought union gains he helped achieve, shared a story of being overwhelmed by 83 hungry Air Force cadets needing lunch. While there were white off-duty staff members on the train at the time, he explained the challenges of asking for their assistance. Through his account, we gain a deeper understanding of the intricacies and misunderstandings surrounding overtime pay during this era and the racialized structures that governed and divided rail workers.

In one of the clearest and most concise wartime stories in Grizzle’s collection, an unknown narrator recounts—despite audible breaks in the sound recording—details of transporting German prisoners of war. While he describes the sleeping cars’ physical environment and the meals served, much is left to the imagination, leaving gaps about how porters perceived this service and the potential dangers they faced. These insights are largely lost to history. Eddie Green builds on this discussion while speaking about the evolution of train technology in the early twentieth century. The reintroduction of outdated train cars to meet wartime demands posed significant challenges and physical dangers for porters, who had to navigate these risks while managing increased passenger loads. The stress would have been tremendous.

In many ways, the final interview clip brings the narrative full circle. In it, Joseph Morris Sealy reflects on how the high demand for wartime rail service paved the way for significant union gains. Government-backed wage increases served as a crucial starting point for negotiating the first collective agreement between the International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the CPR in 1945. There was no going back to the way things were before the war. The uninterrupted movement of people and goods by rail had proven essential to sustaining a stable and functioning economy. Porters, fully aware of the critical role they played, fought to ensure they were treated fairly and justly compensated.

While piecing together the contextual information behind the images included above may not be possible, these accompanying narratives contain enough information to reveal what may have been happening before and after photographers captured these moments in time. They give a voice to the experiences of porters, shedding light on the complexities of their work during and after the Second World War. Yet, as with all historical sources, this oral and photographic evidence underscores the challenges of reconstructing the past—we must work with the fragments available to us. Despite their limitations, these sources compel us to fundamentally rethink our national narrative and the pivotal role of Black labour within it.

Additional Resources

Stacey Zembrzycki is an award-winning oral and public historian of immigrant, ethnic, refugee, and racialized experiences. She is a faculty member in the Department of History and Classics at Dawson College.