By Elaine Young

Did you know that Canadian vessels over a certain size have had to be registered with government authorities as far back as the 18th century? Library and Archives Canada (LAC) holds various types of records related to the registration of vessels and has recently transcribed and made searchable almost 84,000 of these records. The transcriptions include the ship’s name, port of registry, registration number and year of registration, all key fields for researching the rich (and sometimes surprising!) histories of the vessels. These records are a vast resource for researching maritime history across Canada and are also a genealogical tool for tracing the family lineages tied to those ships.

This transcription project is part of LAC’s effort to improve research into the records in its collection. LAC took custody of these records, many of them ledger books, in prior years as Transport Canada (the regulator) moved increasingly towards digital recordkeeping. To support digital access to the records, LAC took digitized copies of some of these ledgers and worked with researchers in the field to identify the best information to transcribe.

The transcribed material relates to ships that were operated then de-registered (closed out) between 1838 and 1983. It includes vessels from the Atlantic, Pacific and inland waterways.

These registries contain a wealth of information about each vessel, including a description, the type of ship, its size, the ownership and when it was built. The registries offer valuable insights for anyone researching shipbuilding, shipping or coastal and open ocean industries. For example, over time these records illustrate the transition from wind to steam-powered ships, as well as the introduction of fibreglass and composite hulls. The records also contain information relevant for genealogical research, as many ships were passed down within families.

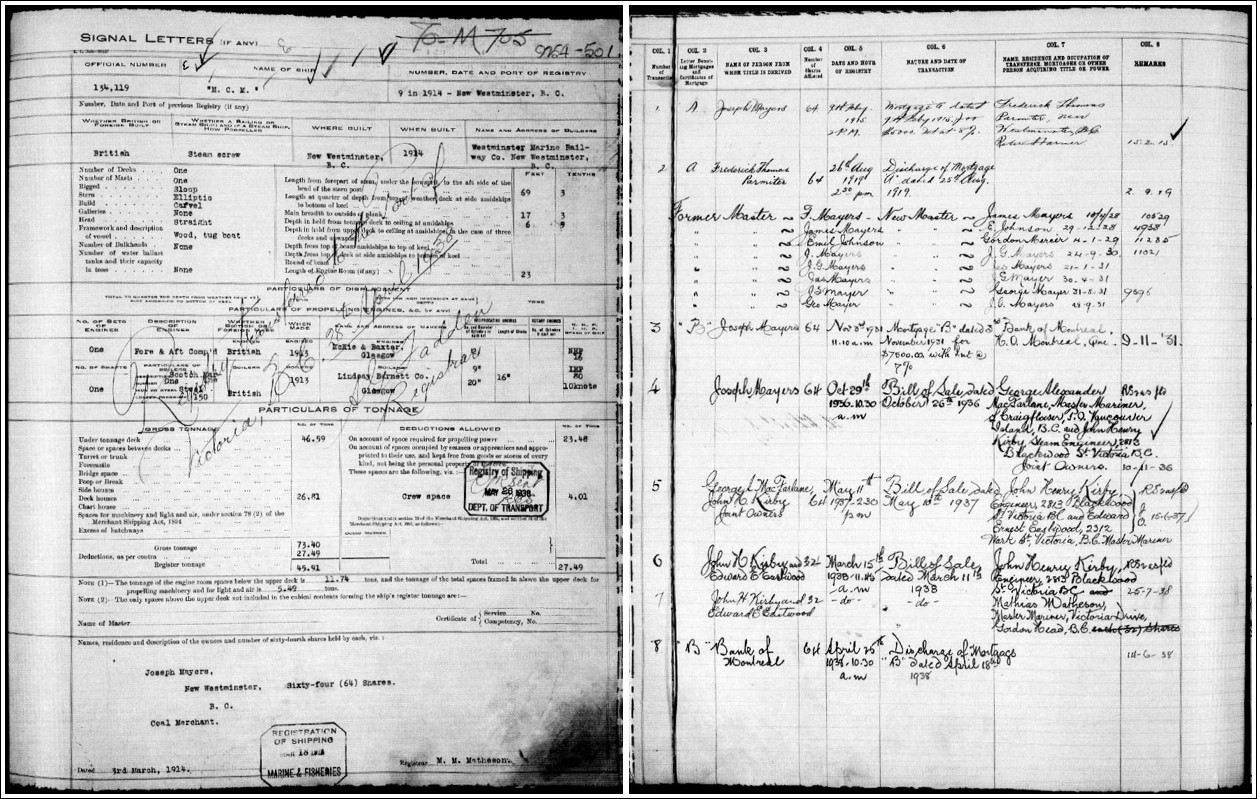

Example of a typical ship registration:

[M.C.M., Port of Registry: NEW WESTMINSTER, BC, 9/1914] R184, RG12-B-15-A-i, Volume Number: 3041. (e011446335_355)

The caption above demonstrates the naming convention that users will see in Collection search: Vessel name / port of registry / a consecutive number assigned for each vessel newly registered at that port in a year / year of registration.

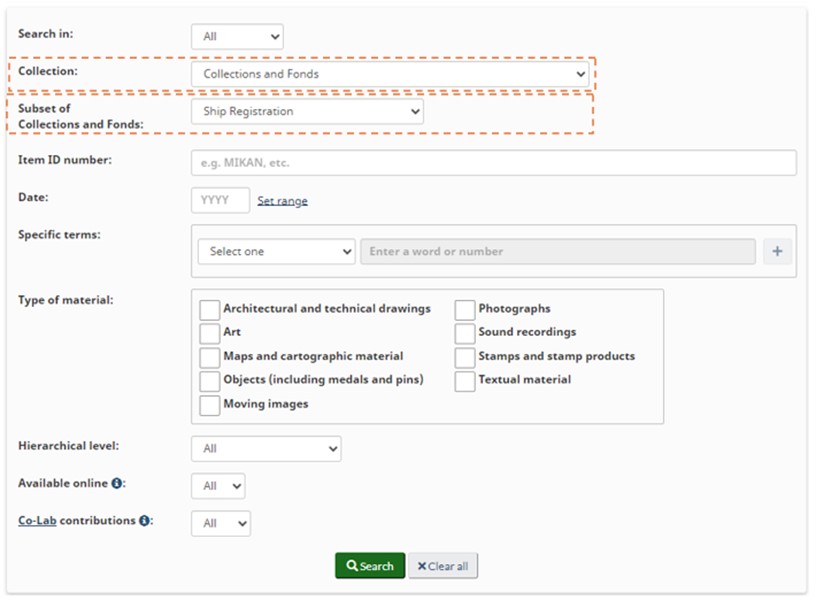

To find the records on LAC’s website using Collection search:

1. Go to advanced search

2. Select “Collections and Fonds” under Collection

3. Select “Ship Registration” under Subset of Collections and Fonds

How to locate Ship Registrations in Collection search. (Library and Archives Canada)

4. To search specific word(s) in the database, enter them in the search bar at the top. You may also enter a date or date range in the Date field (this will reflect when the ship was closed out). If you prefer to browse all ship registrations, leave the fields blank and click “Search.”

How to narrow down your vessel search using keywords and date ranges. (Library and Archives Canada)

For a more specific search, use the “All of these words” field at the top to search by name, port of registry, official number and year of registration.

Name:

- The name is assigned by the owner at the time of initial registration and usually lasts the lifetime of the vessel, but it can be changed (often when there is a change of ownership).

- Once a vessel has been closed out, there is a waiting period before that ship’s name can be used again. Two vessels cannot have the same name at the same time.

- Vessels may have similar, but different names (for example, Karen Dawn, Karen and Dawn, and Karen & Don). Adding a Roman numeral after a name that had been taken remains a common way to create a new name (for example, Dora-Mae II).

Port of registry:

- The port where the vessel was registered.

- Vessels may be registered in ports close to where they were built or operated.

- This can be useful in identifying shipbuilding activity in a specific area.

- Vessel registration may have passed to different ports over time, as owners were expected to update their ship registration to the closest port of registry when they moved or if the ship was sold and transferred to another region.

Official number:

- The unique number assigned to a vessel when it was registered—no other vessel will ever have this number.

- The number remains the same for that vessel’s life, even if it is no longer in service or destroyed.

- The official number can help you find information on that vessel in other record types:

- Appropriation books: books that include the inventory of official numbers assigned to various ports of registry

- Transaction books: books documenting supplemental transactions when the two pages per vessel in a registry book were filled

- Construction books: books documenting ships under construction

- Ship dockets: individual files opened by port of registry offices for specific ships

Year of registration

- The consecutive number, starting from 1, assigned to each ship that was newly registered / (slash) the year that the vessel was registered. For example, 22/1883 would mean the 22nd vessel registered at a particular port of registry in 1883.

The closed-out ship registries can also be accessed via LAC’s staff research list, which provides direct access to the records at the series level. From there, you can navigate to individual ship registration records.

The new searchable ship registries transcriptions make tens of thousands of records accessible in a way that was not possible before. Users can now more easily research information on family histories, shipbuilding, shipping and many other areas. This valuable resource illuminates the complex and varied histories of Canadian shipping and shipbuilding, the communities built around these trades and the lives of the individuals and families who owned these vessels.

The team and LAC wish to thank Don Feltmate residing in Nova Scotia and John MacFarlane residing in British Columbia, who have been tireless advocates for the importance of these records and for making them more accessible.

Additional resources

- Staff research list

- Ship Registrations, 1787-1966

- Transport Canada Vessel Registration Query System (for records post-1984)

- The Nauticapedia

- Maritime Museum of the Atlantic

- The Maritime Museum of British Columbia

- Nova Scotia Archives

Elaine Young is an analyst in the Partnerships and Community Engagement Division at Library and Archives Canada.