By Rebecca Murray

In 2022, I wrote about researching my great-grandfather’s attendance at the 1936 unveiling of the Vimy Memorial. A year later, I shared another instalment, and now, I’m back with what feels like the conclusion to this journey through my family history.

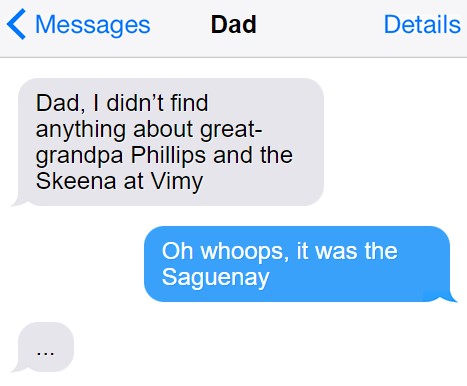

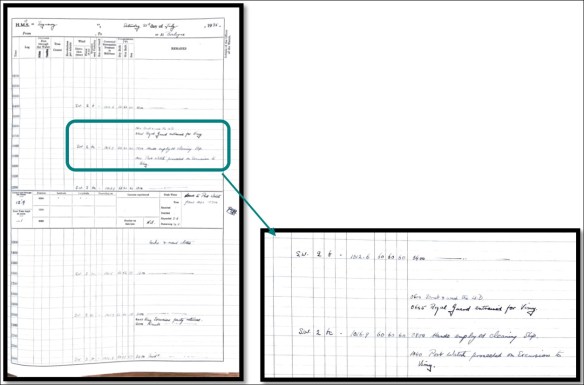

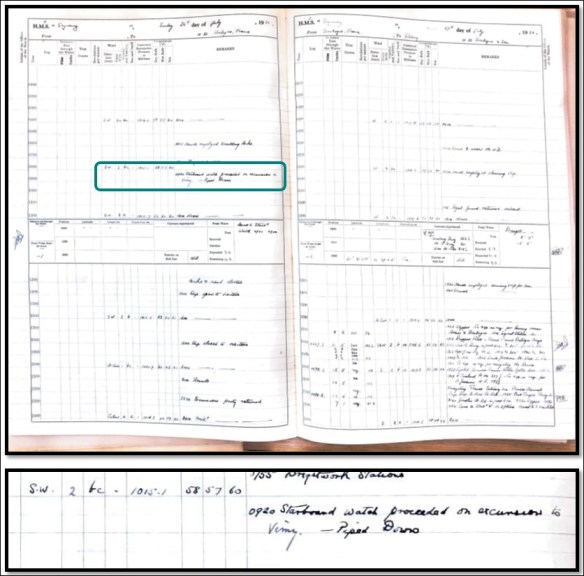

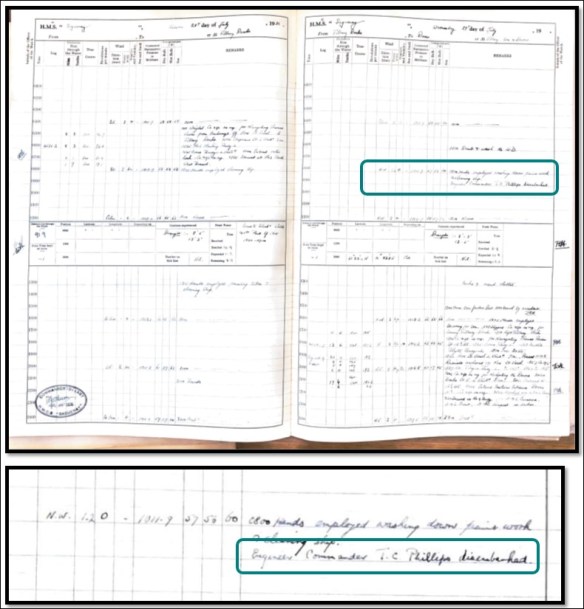

We left off with the exciting discovery that Thomas C. Phillips had indeed been at or very near the Vimy Memorial in July 1936. However, we were still missing a key piece of the puzzle—how exactly did he get there and back home again?

Given the era, it’s likely that Thomas travelled by passenger ship. Family documents tell us that he sailed to France on the SS Alaunia and I confirmed online that this ship left Montréal on July 20, 1936—a tight, but feasible window for him to make it to the unveiling on July 26. So, this is where we pick it back up!

I turned my attention to passenger lists and related records, hoping to trace Thomas’s journey. My first stop—because I have learned that a problem shared is a problem halved AND I know how smart my colleagues are—was the Genealogy Desk! I spoke with one of my colleagues (you can do this too!), who advised me that post-1935 passenger lists are under the custody of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada and are accessible through Access to Information requests. Pre-1935 records, however, are organized into various datasets that are searchable on the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) website using a variety of keywords such as “passenger,” “immigration,” and “border.”

I hummed and hawed over this—those of you who love research will understand that handing over the reins to someone else wasn’t my first choice. Not wanting to rely entirely on others, I approached the research from a new angle. Which angle you ask? Well, I went all the way to the other side of the ocean! Instead of looking for arrival records, I decided to look for departures (or, Thomas’s return trip)! This led me to the National Archives of the United Kingdom and their digitized records on Findmypast, where I discovered not one, but two passengers named Thomas Phillips who sailed to Montréal in the summer of 1936. Another big thank you to my colleagues at the Genealogy Desk, whose expertise proved invaluable in this stage of the research.

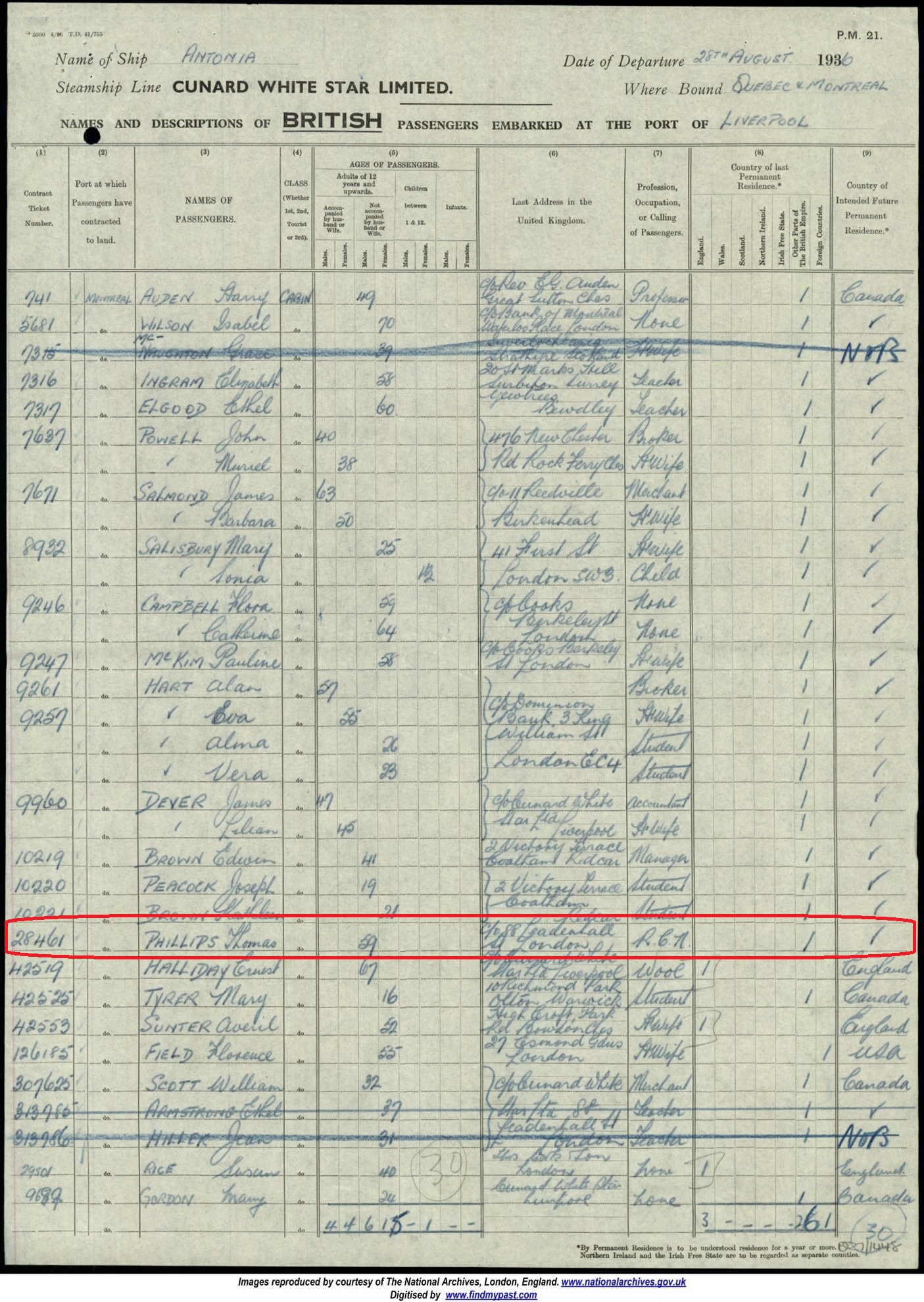

I reviewed the search results knowing that I should look for a departure date in the late summer and use Thomas’s birth year (1877) as an additional filter. I quickly found the relevant record: a passenger list for the SS Antonia, a Cunard ship built in the 1920s. Spotting Thomas’s name felt like one of those moments in the Reference Room where you want to fist pump and high-five someone—except, when you’re working remotely, all you get is a side-eye from the dog for interrupting his nap.

The form tells us a lot about the voyage and about Thomas. The SS Antonia departed Liverpool on August 28, 1936, bound for Quebec City and Montréal, Quebec. While most of the passenger data is standard, I found it neat to see column 8 or “Country of Last Permanent Residence,” which offers a breakdown of regions across the United Kingdom as well as options for “Other Parts of the British Empire” and “Foreign Countries.” Unsurprisingly, most of the passengers heading to Quebec on this voyage are listed as from “Other Parts of the British Empire”—perhaps other Canadian pilgrims who, like Thomas, had been in France the previous month for the unveiling of the Vimy Memorial.

Passenger list for Cunard White Star Line’s SS Antonia with a departure date of August 28, 1936, from Liverpool, England. Information about Thomas Phillips is circled in red. Source: National Archives of the United Kingdom.

We also learn that Thomas’s last address in the United Kingdom was “c/o 88 Leadenhall St, London.” Naturally, my curiosity led me to investigate what was located at 88 Leadenhall Street in 1936. A quick Internet search revealed it was Cunard House, an eight-story building that housed the business offices of Cunard Line and its affiliated companies. Further digging suggested that it wasn’t uncommon for travellers by sea to use a “care of” (c/o) address, likely for ease of correspondence during their journey.

With this new information in hand, I turned to LAC’s archives to explore what else I could find about the SS Antonia and Thomas’s voyage. Archival holdings at LAC provide a rich narrative of the SS Antonia—from her early days as a passenger liner to her later role as a troop transporter during the Second World War. But of most interest to this researcher are the records related to the Vimy Pilgrimage! LAC even holds footage of the SS Antonia, as well as this beautiful photograph of her Europe-bound voyage earlier that summer.

Members of the Vimy Pilgrimage aboard the SS Antonia, departing from Montréal, Quebec, 1936. Source: Clifford M. Johnston/Library and Archives Canada/PA-056952.

I even scoured Montréal newspapers from early September to see if Thomas’s return was noted in the shipping news. While the Antonia’s arrival was documented, my great-grandfather didn’t make the papers. And so, this brings me to the conclusion of my research—sometimes the hardest part of archival work is knowing when you’re done.

I’ve delved into the original question of why my great-grandfather attended the unveiling of the Vimy Memorial, and along the way, uncovered answers to how he made the journey there and back. The research brought both exciting discoveries and inevitable disappointments—common in any archival exploration. Along with new insights, I’ve gained valuable research skills, which is always a welcome bonus. And far from feeling discouraged, I’m more eager than ever to tackle the next family history mystery. Bring it on!

Rebecca Murray is a Literary Programs Advisor in the Outreach and Engagement Branch at Library and Archives Canada.