Version française

By Jeff Noakes

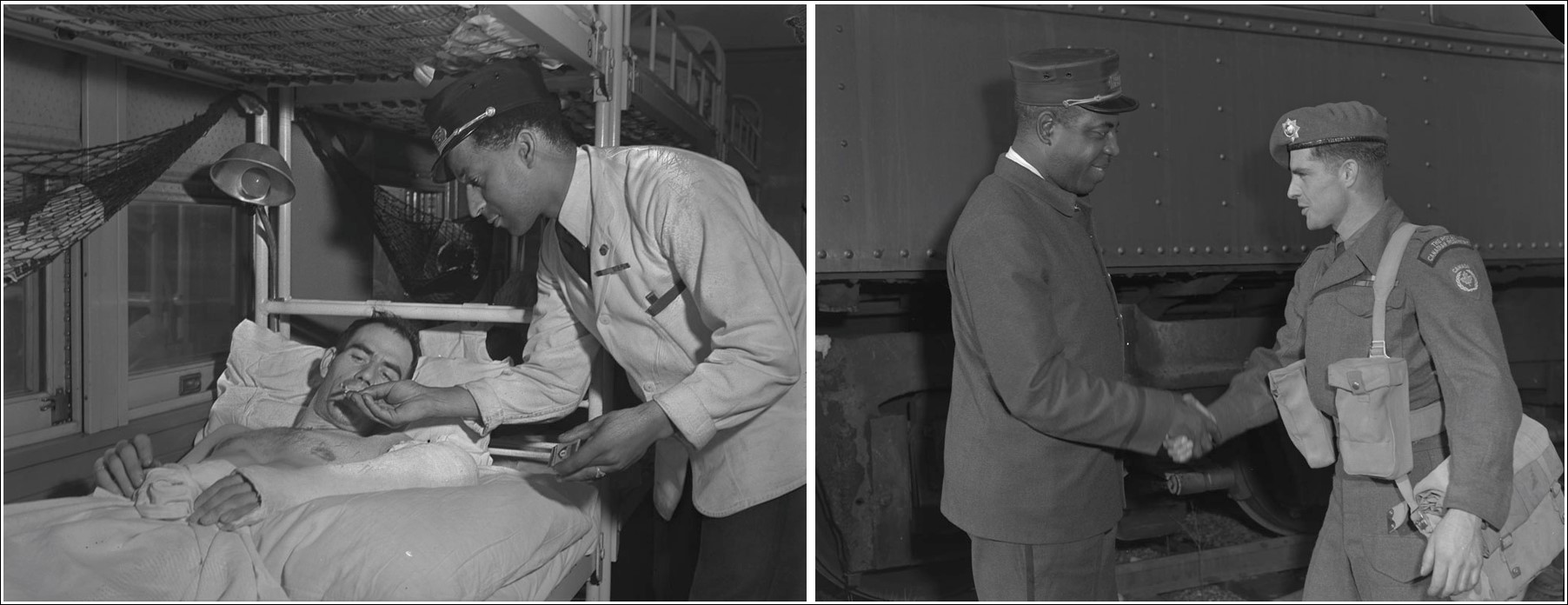

Porter Jean-Napoléon Maurice (right) leans over to light the cigarette of Private Clarence Towne, a patient on a hospital train, August 20, 1944. (e011871941)

The image above comes from a series of photographs of Black sleeping car porters from during and after the Second World War. This series documents service to country through various vantage points. It also forces us to ponder the backstories to the images. Who appears in these photographs? Why were they taken? Why are they significant? And what stories can they help us uncover?

The date and original cataloguing provide enough information to look further into parts of some of these stories. As a photograph taken for public consumption, this image soon appeared in Canadian newspapers, which identified the two men appearing in the image: Porter Jean-Napoléon Maurice and Private Clarence Towne. Newspaper captions also provided some additional information about both men, noting that Maurice had served with the Royal 22e Régiment and had been wounded in Italy, while Towne had been wounded in fighting at Caen, in Normandy. Not mentioned in some instances is Maurice’s earlier service with Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, including his participation in the Dieppe Raid.

While Maurice’s military service is explicitly mentioned in the newspaper caption, it is also conveyed through his uniform. Visible on his white jacket are medal ribbons, along with the shield-shaped General Service Badge that he was entitled to wear because of his military service. Both would have been readily recognized by many viewers at the time. Towne’s service, and his wounds, are clearly depicted by his left arm, encased in a plaster cast. In at least one newspaper, the photograph was retouched to make the white cast more clearly visible against the bedsheets.

The photograph was very likely intended as part of a wider publicity campaign relating to hospital trains. Maurice was one of four Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) porters who were veterans, had been wounded in service and were chosen to work on such trains. Stories about these four men—along with Maurice, they were identified in newspapers as Randolph Winslow, Sam Morgan and James E. Thompson—their military service and their work as porters, including the photograph seen above, appeared in late August 1944.

The date and original caption also furnish enough information to conduct further research into records held by Library and Archives Canada (LAC). While there was no “Lady Nelson Hospital Train,” one of Canada’s Second World War hospital ships was the Lady Nelson. Originally a civilian ocean liner, in 1942 the ship was sunk in the harbour at Castries, Saint Lucia, by a German submarine. After being salvaged, the Lady Nelson was converted into a hospital ship for transporting wounded, injured and sick military personnel; it would later be used to repatriate other military personnel and their dependents. Its voyages included trips from ports in the United Kingdom to Halifax, Nova Scotia. From there, hospital trains, using equipment provided by both the Canadian National Railway (CNR) and the CPR, transported patients to destinations across the country. The photograph, therefore, depicts a scene aboard a hospital car in one of these trains, carrying patients from the Lady Nelson.

During the Second World War, responsibility for many aspects of these operations fell to the Department of National Defence’s Directorate of Movements. Its records form part of the Department of National Defence fonds at LAC [R112-386-6-E, RG24-C-24]. This substantial collection covers the movement of hundreds of thousands of military personnel to and from Canada, as well as the transportation of cargo and military equipment. It also includes extensive records relating to the movement to Canada of military dependents, including war brides and their children, during and after the war. The records, which were microfilmed around 1950, are now available on digitized microfilm at Canadiana by the Canadian Research Knowledge Network.

Advisory: these records are in English only and can include medical information that some people may find disturbing, offensive or potentially harmful, including historical language used to refer to medical diagnoses. The records can also contain other historical language and content that may be considered offensive or potentially harmful, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. The items in the collections, their content and descriptions reflect the period in which they were created and the views of their creators.

These records include files relating to the movements of hospital ships and the personnel they repatriated, as well as the planning and operation of the hospital trains and other means of transportation that brought these patients to points across Canada and in Newfoundland. In some cases, these voyages extended even further. This included the repatriation of Americans serving in the Canadian military, as well as members of Allied militaries whose lengthy homeward journeys took them through this country.

Since the cataloguing information notes that this photograph was taken on August 20, 1944, it suggests a connection with an arrival by the Lady Nelson a few days before. A search of the LAC catalogue turns up a Directorate of Movements file [RG24-C-24-a, Microfilm reel number: C-5714, File number: HQS 63-303-713] for such an event on August 18, although the ship may in fact have docked just before midnight on August 17. As a result, the photograph offers an entry point into what the records of this specific voyage contain. It also provides an opportunity to discuss how these sorts of records can be useful, as well as some of their inherent limitations, especially with respect to the experiences of sleeping car porters on these hospital trains.

The Canadian hospital ship Lady Nelson in Halifax, Nova Scotia. (e010778743)

This particular file’s hundreds of pages of messages, letters, memos and lists of repatriated personnel provide a general outline of these events. When the Lady Nelson left Liverpool shortly before midnight on August 8, 1944, it was carrying a total of 507 personnel to Halifax for medical reasons. Nearly all were members of the Canadian military, with some 90 percent from the Canadian Army. The ship was also transporting two Newfoundlanders who had served in Britain’s Royal Navy, as well as one Royal New Zealand Air Force officer on his lengthy way home via Canada. Two patients died during the trip and were buried at sea: Private George Alfred Maguire on August 11 and Captain Theodore Albert Miller on August 15. Their service files, digitized and available through LAC’s catalogue, help provide some details of their final voyages.

The file for this trip also reflects a number of broader stories, in particular the way that wounded, injured and sick military personnel were being returned to Canada from overseas. In mid-August 1944, this capacity was about 500 at a time aboard the Lady Nelson. The following month, a second Canadian hospital ship, the Letitia, entered service, with the ability to transport around 750 patients. At that point, some 1,000 or more wounded, injured and sick could be repatriated every month across the North Atlantic to Canada.

The need for this augmented capacity speaks to the growing number of repatriations arising from increased combat activity overseas following the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944, and the subsequent campaign in Normandy. The casualties from this fighting added to the ongoing toll of the land campaign in Italy and the war at sea and in the air; a mid-August memorandum refers to a “back log” of casualties in the United Kingdom awaiting repatriation to Canada. The records also make it clear that in addition to those whose wounds, both physical and psychological, were suffered in battle, the patients included those being repatriated for non-combat injuries and for illnesses of various sorts.

The focus of the Directorate of Movements for these voyages was on the personnel returning home, including identifying their medical requirements during their travels and at their destinations. The records consequently provide details of personnel down to the individual level, with lists of those being transported to various locations across Canada, their medical status and their care needs, as well as information about their next of kin.

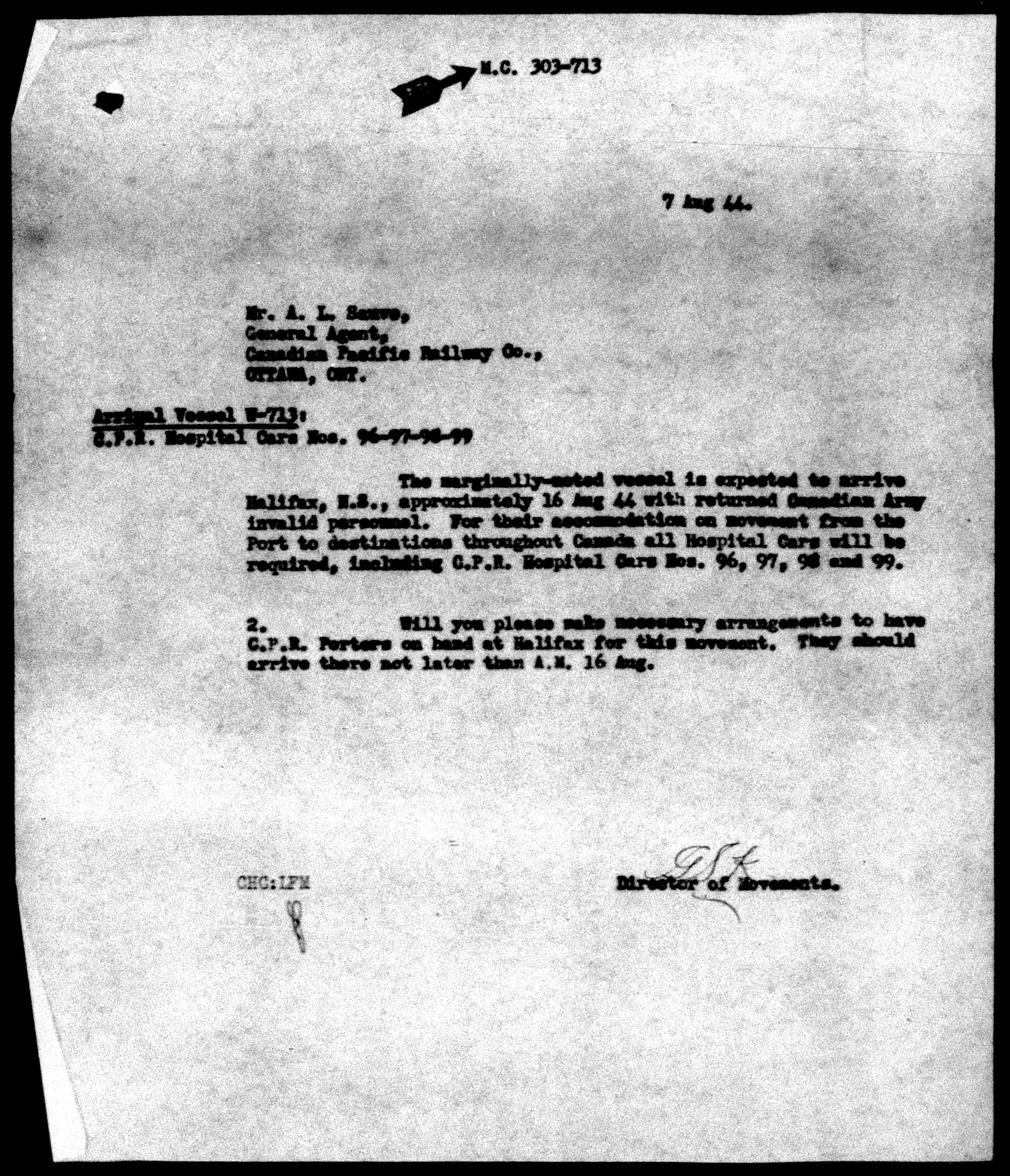

The records also detail the provision of services to help make these voyages happen, but generally do not discuss those who did this work. Hospital train crews and staff provided by the railways, including porters, do not appear as individuals. While there was one porter assigned to each hospital car in addition to medical staff, as well as porters in other passenger and sleeper cars that made up the trains, the porters themselves and their experiences do not truly speak in these documents. They appear briefly and anonymously in the files as requirements for the hospital trains and indirectly in comments that are made about the train staff and crews more generally. As part of a service being provided by the railways, the porters were an operational requirement, who the military wrote about and recorded in the same way that the remainder of the personnel operating the trains were described.

In the roughly four hundred pages of documents relating to this voyage of the Lady Nelson and the hospital train in Canada, there is only one clear and unambiguous mention of porters. A letter from the Directorate of Movements to the Canadian Pacific Railway in early August 1944 alerted the company to the anticipated arrival of the Lady Nelson on or around August 16. In addition to noting that hospital cars would be required for the movement of patients, the letter also requested that porters be on hand for the train. Four CPR hospital cars were identified, each of which required a porter. Given the railway’s decision to provide hospital car porters who had been wounded during their military service, this would have meant Jean-Napoléon Maurice and his three comrades.

This letter from the Directorate of Movements to the Canadian Pacific Railway Company is the only clear and direct reference to porters in the Directorate of Movements file relating to the arrival of the Lady Nelson in mid-August 1944. (MIKAN 5210694, oocihm.lac_reel_c5714.1878)

Transcript for the letter above:

M.C. 303-713

7 Aug 44.

Mr. A.L. Sauve,

General Agent,

Canadian Pacific Railway Co.,

OTTAWA, ONT.

Arrival Vessel W-713:

C.P.R. Hospital Cars Nos. 96-97-98-99

The marginally-noted vessel is expected to arrive Halifax, N.S., approximately 16 Aug 44 with returned Canadian Army invalid personnel. For their accommodation on movement from the Port to destinations throughout Canada all Hospital Cars will be required, including C.P.R. Hospital Cars Nos. 96, 97, 98 and 99.

2. Will you please make necessary arrangements to have C.P.R. Porters on hand at Halifax for this movement. They should arrive there not later than A.M. 16 Aug.

[Signature]

Director of Movements.

CHC:LFM

Directorate of Movements records are more forthcoming about Clarence Towne. They note that he had served with the North Nova Scotia Highlanders and had been wounded in the left elbow and arm by German machine gun fire. Assigned to one of the beds in hospital car 98, he was travelling home to his wife Jane in St. Catharines, Ontario. Towne might have been chosen as a representative patient because, while he was travelling in a hospital car, his wounds would not have been graphic, disfiguring or unsettling for viewers on the home front. The same could not be said for some of the other personnel being repatriated. Towne’s injuries were safely and indirectly depicted by the cast encasing his left arm. Unlike some of the other patients aboard the train, they were also physical and the direct result of combat, rather than being psychological or the result of accident or illness, which may also have played a role in his selection.

In addition to serving as an entry point for unpacking individual stories using a variety of sources, this photograph makes visible the wider history of the essential service of porters in the functioning of hospital trains during and immediately after the Second World War. At the time of its creation, it also likely served other functions. By showing Jean-Napoléon Maurice lighting Clarence Towne’s cigarette, it may have been intended to build on and reinforce popular perceptions and depictions of Black railway porters, the nature of their jobs and their racial and social status, especially how these were manifested through their role in serving travellers.

The photograph also incidentally serves as a reminder of the prevalence of tobacco and smoking in the 1940s. Among their many features, the specially modified hospital cars were equipped with an ashtray for each of the patient beds—something that would be unbelievable today. By depicting personal interactions such as the lighting of a cigarette, the scene was likewise meant to show the attention being paid to military patients. Images such as this provided an opportunity for the Canadian military and government to demonstrate the care being provided to those being repatriated, an important consideration given that the hospital trains and their passengers were a powerful home front manifestation of the increasing human costs of the Second World War.

Additional Resources

Jeff Noakes is Historian, Second World War, at the Canadian War Museum.