By Normand Laplante

December 21, 2016 marks the 125th anniversary of the invention of basketball by Canadian James Naismith and of the first game ever played. In the fall of 1891, Naismith was studying to become a YMCA physical education instructor at the International YMCA Training Institute in Springfield, Massachusetts. He was given the task of finding a suitable indoor recreational sport for a physical education class for men aspiring to become executive YMCA secretaries. This group of “incorrigibles” had shown little interest in undertaking traditional calisthenics and gymnastics exercises and their reluctance had led the two previous physical instructors assigned to the group to quit. Naismith first attempted to have the class play modified indoor versions of football, soccer and even the Canadian game of lacrosse. However, these initiatives proved unsuccessful, largely due to the physical restraints imposed by a small gymnasium. Naismith then came up with the idea of a new sport, based on a children’s game Duck on the rock, where two teams would battle each other to throw a ball into the opposing team’s basket to score points. On December 21, 1891, Naismith presented his 13 rules for the new game to the class and separated the group into two teams of nine players. While the final score of the game was only 1-0, the new sport proved to be a big hit with the players.

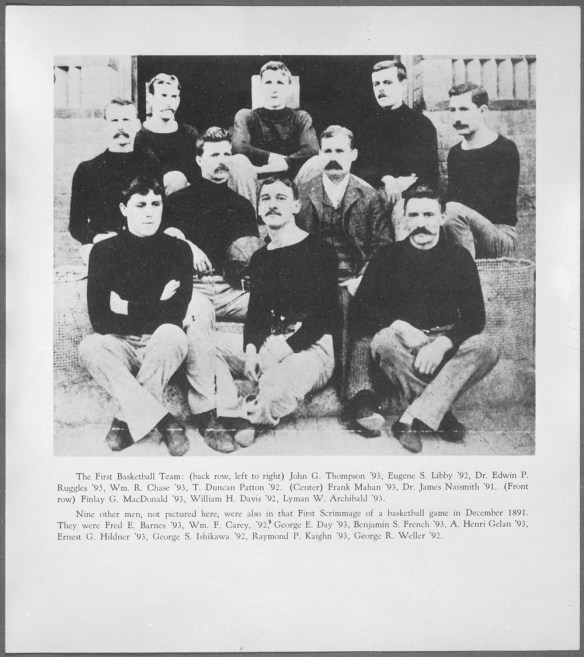

Members of the world’s first basketball team, Springfield, Massachusetts, 1891 (c038009-v8)

The participants in the first game included four Canadians who, like Naismith, were studying at the International YMCA Training Institute in Springfield: Lyman W. Archibald, Finlay G. MacDonald and John George Thompson, from Nova Scotia, and Thomas Duncan Patton, from Montreal. As graduate trainees of the Institute returning to their new duties in Canada, some members of the “First Team” were

instrumental in spreading the new sport through the YMCA network in different regions of Canada.

Lyman W. Archibald, Springfield, Massachusetts, 1891 (c038009-v8)

Originally from Truro, Nova Scotia, Lyman W. Archibald (1868-1947) became general secretary and physical director of the St. Stephen, New Brunswick, YMCA in 1892 and organized one of the first basketball games played in Canada in the fall of 1892 in this town on the Canada-US border. In 1893, Archibald moved on to Hamilton, Ontario where, as a YMCA physical instructor, he brought the sport to that region.

Update (January 2024): While the St. Stephen court is the oldest surviving basketball court in the world, new research reveals that it is highly probable Ottawa is the birthplace of the sport in Canada, since it was the first place on record to organize a game of basketball. As described in The Ottawa Journal newspaper, the first recorded game took place at the Ottawa YMCA on Monday, October 3, 1892, when the facility reopened for the winter. This was less than 10 months after the first ever basketball game played at Springfield College under Dr. Naismith.

John G. Thompson, Springfield, Massachusetts, 1891 (c038009-v8)

After graduating from the YMCA Training Institute in 1895, John G. Thompson (1859-1933), from Merigomish, Nova Scotia, returned to his home province and, in 1895, was appointed physical education director at the new YMCA building in New Glasgow, where he introduced basketball to the Pictou County region.

T. Duncan Patton, Springfield, Massachusetts, 1891 (c038009-v8)

T. Duncan Patton (1865-1944), originally from Montreal, was one of the two team captains selected by Naismith for the first game. He is said to have introduced the sport to India as a YMCA missionary in 1894. Later on, as YMCA secretary in Winnipeg in the early 1900s, Patton influenced the early organizers of the game in that city.

Library and Archives Canada (LAC) holds the D. Hallie Lowry collection which includes photographs of Naismith and of participants of the first basketball game in Springfield. The National Council of Young Men’s Christian Associations of Canada fonds includes a copy of James Naismith’s 1941 book, Basketball: Its Origins and Development, autographed by some of the members of the first basketball team, including Canadians T. Duncan Patton and Lyman W. Archibald; and Patton’s personal published account of the origins of the sport, Basketball: How and When Introduced, written before 1939. LAC’s collection also has photographs of early basketball teams which provide visual documentation of the development of the sport in Canada.

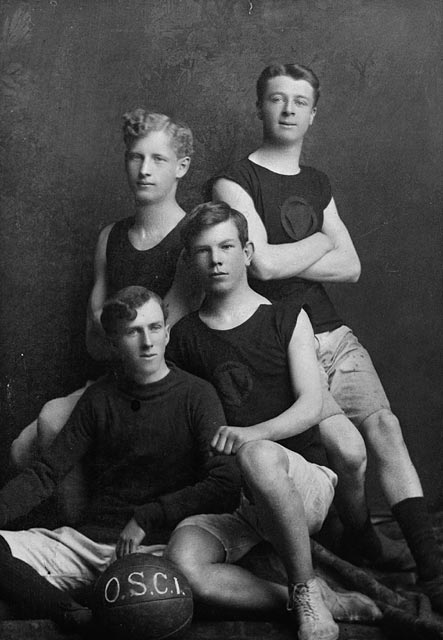

An early photograph of a Canadian basketball team which included Norman Bethune (second from the bottom) with Clark, Lewis and McNeil, members of the Owen Sound Collegiate Institute basketball team, ca 1905 (a160721)

Related Links

Normand Laplante is a senior archivist in the Society and Culture Division of the Private Archives Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

Update (January 2024): Leo Doyle is the founder of the Ottawa Basketball Network, a not-for-profit organization that advocates for improved growth and equitable access to the game of basketball.