By Sacha Mathew

Did you know that you can easily make your own military heritage display by using the tools and digitized records found on the Library and Archives Canada website? Using the display we presented at a recent event as an example, I’ll show you step-by-step how you can make your very own display at home or at school.

Library and Archives Canada held a hugely successful Open House event in May, welcoming more than 3000 visitors to our Gatineau facilities and allowing them to enjoy an opportunity to view treasures in our vaults.

This small display of photographs and textual documents from our military collection was very popular. It had a personal touch, and many visitors asked us how we selected the records to display.

Your display can easily be tailored to present a person, an anniversary or a specific military unit. In our case, we wanted to highlight the 100th anniversary of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) taking place this year. That was our starting point.

Next, we needed to narrow our focus to make it easier to tell a story. Records give facts, but they don’t tell a story — that’s where interpreting the records comes in. Since the event was in Gatineau, we thought the public would be interested in exploring the personal stories of servicemen from the local area. We started by choosing the 425 “Alouette” Squadron, an RCAF unit. This is a French-Canadian bomber squadron established at the outbreak of the Second World War. By researching the 425 Squadron personnel roster and cross-referencing it with a list of RCAF casualties provided by the RCAF Association, we were able to find two local airmen: one from Montreal and the other from Ottawa.

Pilot Officer J.W.L. Tessier; Pilot Officer J.A. Longmuir, DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross) of the Royal Air Force, attached to the Alouette squadron as Bomber Section Training Officer; and Flight Lieutenant Claude Bourassa, DFC, Commander of the French-Canadian squadron’s bomber section. 425 Squadron. 24 April 1945, PL-43647, e011160173.

For our display, we looked for specific individuals to feature in our display, which can also be done for local service members from your community or school. Choosing an individual is even easier if you are making a display for a family member, since you may already have someone in mind.

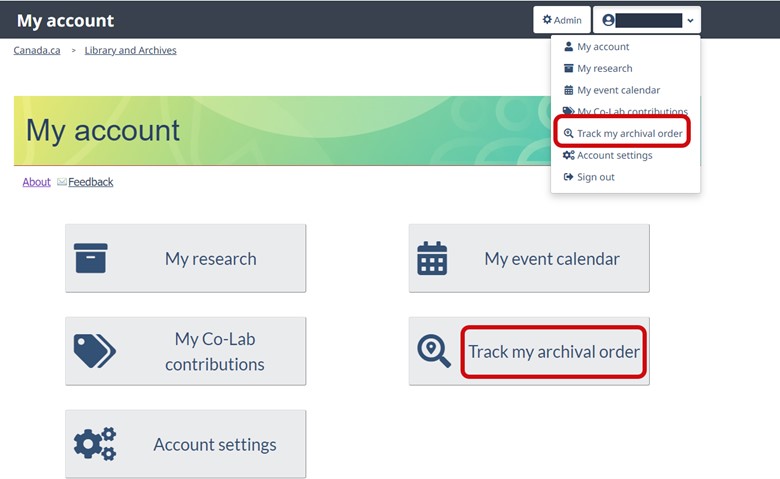

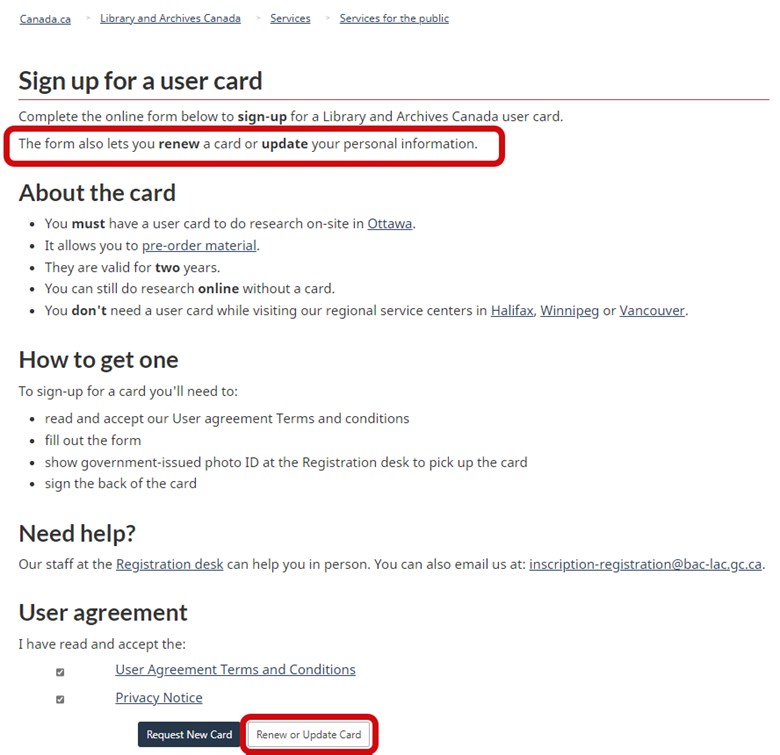

Once you’ve chosen an individual, you may look for their military personnel file. This file provides a tremendous amount of information and includes personal details (ever wonder what your great-grandfather’s address was in 1914?). The file can be easily found on the LAC website. However, it should be noted that not all records are open to the public and available online. All personnel files for the First World War are open and have been digitized (First World War Personnel Records), but only “War Dead” files are available online for the Second World War. “War Dead” refers to members that died during the war (Second World War Service Files – War Dead). Other Second World War and post-Second World War service files can still be obtained, but they must be requested through an Access to Information and Privacy request (Records you may request).

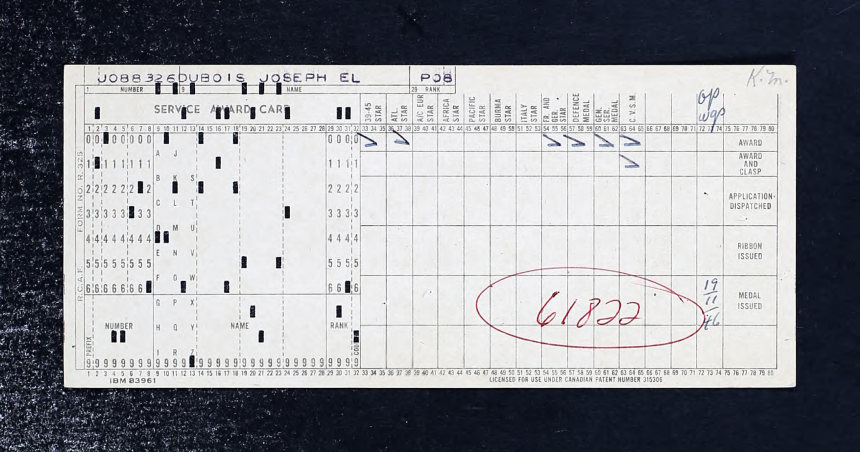

DUBOIS, JOSEPH EDWARD LAWRENCE, Service Award Card “Medal Card”, Second World War Service Files – War Dead, 1939 to 1947.

Now that you have the service file, you can decide what you want to display. For our display, we were limited by the size of the display case. If you have more space, you can pick as many documents as you like. You’ll find a variety of documents in the service file. For our airman, Pilot Officer (PO) J. Dubois, we selected a few documents that we found interesting: a letter of recommendation from his employer (T. Eaton & Co), his attestation papers, his medal card, his pay book, official correspondence with his parents in French and the report on his death. You can scroll through and read the digitized service file, then choose what you’d like to feature. Please remember to cite your sources, including reference numbers for archival documents.

DUBOIS, JOSEPH EDWARD LAWRENCE, RCAF Service Book “Pay Book”, Second World War Service Files – War Dead, 1939 to 1947.

As mentioned, interpreting the records you find can help you tell a story rather than just display your research. In the case of PO Dubois, we looked to his squadron records from the day he died, and we were able to better understand the circumstances of his final flight. Each of the three services has an official unit journal of their daily actions. They are called “War Diaries” for the Army, “Ship’s Logs” for the Navy and “Operations Record Books” for the RCAF. The personnel file gives you biographical information, and the unit journal gives you the context. The journal allows you to understand how the individual fits into the unit’s operations. You would interpret the documents by examining them together, giving you a much broader picture. That picture is the story, which you could write up or present orally.

The only thing remaining is to add some photos to make the display more visually compelling. You may find the member’s photo in the service file, but this is not common for files from the World Wars. To find photos, I suggest setting Collection Search to “Images”. Here you can search by the unit designation and choose a few photos that are appropriate to the time frame that you are looking at. For our display, we easily found a few photos of 425 Squadron in England during the 1940s. Like the textual documents, it is important to give accurate photo credits for any photographs used in your display.

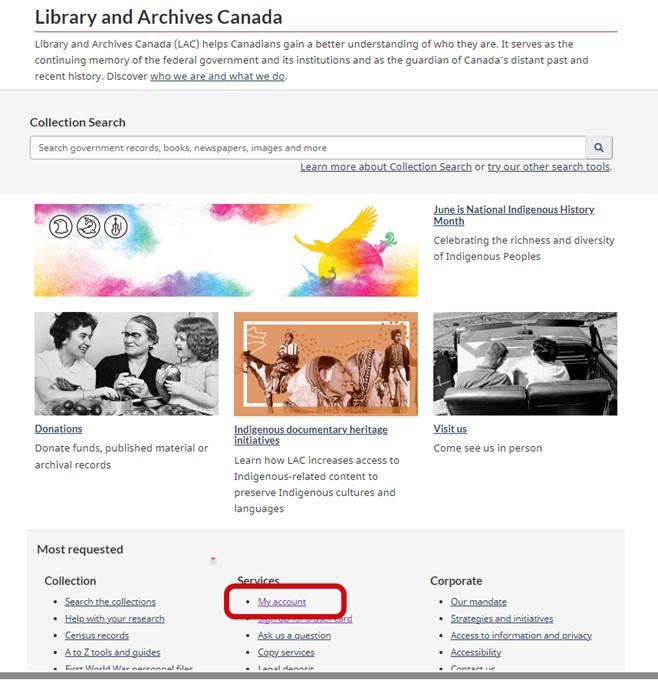

Collection Search, LAC website.

By using the tools and resources from LAC’s online collection, you can make your own custom display for an individual or for a unit. It’s your choice how you’d like to present your display: you can print copies of documents and photos to make a framed display or scrapbook, or you can make a digital presentation. Making a display is an excellent way to connect with ancestors by learning about their lives, and it allows people to explore Canadian military heritage in a personal way. It is also an excellent research exercise and would prove a wonderful Remembrance Day project for young students.

Sacha Mathew is an archivist in the Government Archives Division at Library and Archives Canada.