By Ariane Gauthier

I learned about Marcel Gauthier a few years ago when I was visiting the Canadian cemetery in Beny-sur-Mer in France. Although we have the same last name, Marcel is not my ancestor. However, I have always kept a memory of this young man—the only Gauthier buried in this large cemetery. With the release of the 1931 census, I finally had the opportunity to learn more about him. Now, I would like to demonstrate how the many resources of Library and Archives Canada (LAC) can help piece together the life of a person, such as an ancestor or a soldier!

This first part of the blog will cover Marcel Gauthier’s life from his childhood to his military enlistment.

Photograph of Private Marcel Gauthier, age 21, published in an Ottawa newspaper to announce his death overseas (Canadian Virtual War Memorial).

Private Marcel Gauthier (Joseph Jean Marcel Gauthier)

- C/102428

- Le Régiment de la Chaudière, R.C.I.C.

- Date of birth: November 18, 1922

- Date of death: July 15, 1944

- Age at time of death: 21 years old

His military service file is available in LAC’s War Dead database, 1939 to 1947.

Born on November 18, 1922, in Ottawa, Ontario, Marcel Gauthier is the seventh child of a large French-Canadian family of nine. When we look at the Gauthiers in the censuses, we learn that Henri, the father of the family, is from Rigaud, Quebec. When he arrived in Ottawa, he settled in Lowertown with his family. This is where Marcel built his life before enlisting.

At that time, Ottawa’s Lowertown attracted many Franco-Ontarians. The 1931 Census shows that the homes and dwellings of the By Ward – St. George’s Ward sub-district were largely inhabited by French Canadians. Some of them were born in Ontario, others came from Quebec. Several historical studies indicate that the population of Lowertown was mainly Francophone, with a significant Irish population as well. This is one of the reasons why this area has been the site of many language issues in the history of Franco-Ontarians, particularly on the issue of Regulation 17 (available in French only), adopted in 1912. Additional resource: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/ontario-schools-question.

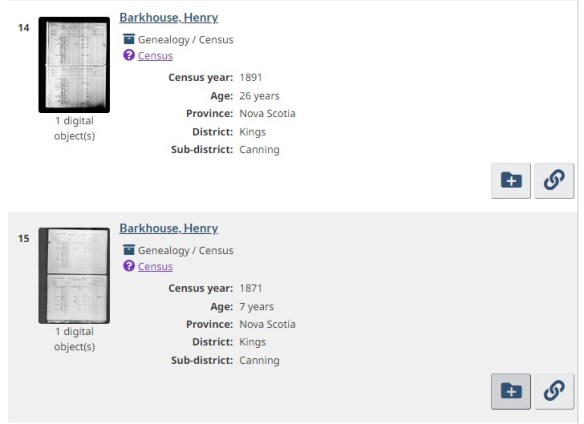

Screenshot of the 1931 Census. Marcel Gauthier’s name is found on the 48th line of the By Ward – St. George’s Ward sub-district, No. 74 (Lowertown), on the 7th page of the document (record 8 of 13). He was nine years old at the time (MIKAN 81022015).

Lowertown was considered a disadvantaged neighborhood with a predominantly working-class population. We can therefore assume that Marcel was not born into wealth. His large family lived in close quarters, first at 199 Cumberland Street, with at least seven children (1921 Census), then at 108 Clarence Street, with nine children (1931 Census).

The absence of his mother, Rose Blanche Gauthier (née Tassé), from the 1931 Census indicates that she had probably died by this time. We can assume, by referring to the 8th page of the document (or record 9 of 13), that she died between 1928 and 1931. This theory is based on the registration of the youngest family member, Serge Gauthier, three years old at the time. Marcel’s military record validates this theory and confirms Mrs. Gauthier’s death on October 6, 1928, possibly due to complications arising from the birth of her last child. She is buried in the Notre-Dame Cemetery in Carleton Place, Ontario, where she was born.

In 1931, Marcel’s father and eight of his children lived in a nine-bedroom apartment at 108 ½ Clarence Street. If it had not been for the help of the older children, Henri’s mail carrier salary would not have been sufficient to support his children and cover their tuition. We can therefore assume that Yvette (24 years old and single), the oldest in the household, looked after the home and the younger siblings. We also know that Léopold (22 years old) worked as a driver and that Marie-Anne (21 years old) was a salesperson. It is very likely that they were helping their father financially, just as their older sister, Oraïda (27 years old), had more than likely done ten years earlier. She had now moved out and married a Mr. Homier.

In 1931, Marcel became a student and learned to read, write and communicate in English. At 16, he completed his education. He entered the workforce as a cook and then moved alone to 428 Rideau Street.

Bowles Lunch restaurant where Marcel Gauthier worked before enlisting in the army in 1943 (a042942).

In Europe, tensions with Hitler’s Germany escalated and led to the outbreak of World War II in 1939. Unlike many young men, Marcel did not immediately feel the need to join the fight, likely because he was satisfied with his job as a cook at Bowles Lunch. He waited until January 11, 1943, before reporting to Enlistment Office No. 3 in Ottawa. We can theorize that, like many, he wanted to help change the course of the war or that he wanted to follow the example of two of his brothers, Conrad and Georges Étienne.

Shortly after, on January 29, 1943, he left Ottawa to begin training in Cornwall, unaware that he was leaving his hometown forever.

Additional resources

- The Life of Private Marcel Gauthier (Part 2) by Ariane Gauthier, Library and Archives Canada Blog

- Have you heard of Léo Major, the liberator of Zwolle? by Gilles Bertrand, Library and Archives Canada Blog

- D-Day and the Normandy Campaign, June 6 to August 30, 1944 by Alex Comber, Library and Archives Canada Blog

- Census Search, database, Library and Archives Canada

- Canadian Virtual War Memorial, database, Veterans Affairs Canada

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission, database, Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Ariane Gauthier is a reference archivist in the Access and Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.