By Ariane Gauthier

I first learned about Marcel Gauthier a few years ago when I was visiting the Bény-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery, in France. Although we share the same surname, Marcel is not my ancestor. Still, I have always remembered this young man—the only Gauthier buried in this large cemetery. With the release of the 1931 Census, I finally had the opportunity to learn more about him. As a result, I would like to share with you how the many resources of Library and Archives Canada (LAC) can be used to piece together a person’s life, such as an ancestor or a soldier.

The second part of this blog will explore Marcel Gauthier’s life, from his military enlistment to his death.

Photograph of Private Marcel Gauthier, age 21, published in an Ottawa newspaper to announce his death overseas (Canadian Virtual War Memorial).

Private Marcel Gauthier (Joseph Jean Marcel Gauthier)

- C/102428

- Le Régiment de la Chaudière, R.C.I.C.

- Date of birth: November 18, 1922

- Date of death: July 15, 1944

- Age at time of death: 21 years old

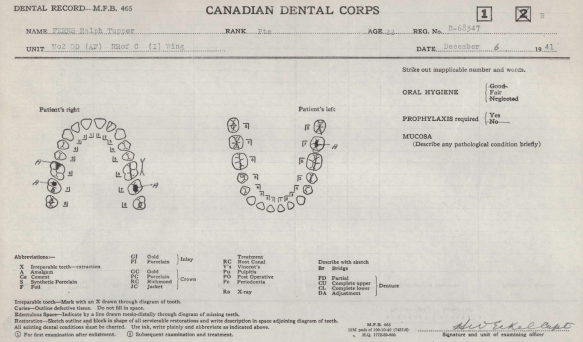

His military record is available in LAC’s database Second World War Service Files—War Dead, 1939 to 1947.

On January 29, 1943, shortly after enlisting, Marcel left Ottawa to begin training in Cornwall, unaware that he would never see his hometown again.

Despite the convictions that led him to join the army, Marcel is not a model soldier. In Cornwall, he left his station, the camp hospital, without official permission. His seven-day absence resulted in disciplinary action being taken against him in the form of monetary penalties—in this case, the loss of three days’ pay—for being AWOL (absent without official leave). The rest of his training is without further incident. On April 1, 1943, Marcel is transferred to the Valcartier base where he joins the Voltigeurs de Québec infantry unit. On July 11, 1943, Marcel embarked on a ship bound for England, where he would train alongside 14,000 other Canadian soldiers in preparation for the Normandy landings. On September 3, 1943, he was transferred to the Régiment de la Chaudière, with which he would storm Juno Beach on the fateful day of June 6, 1944.

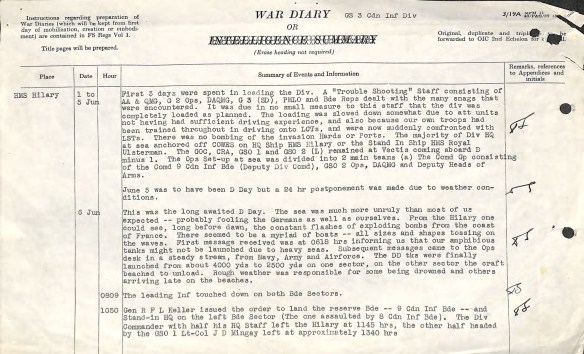

Training for the Normandy landings is very well documented, thanks in particular to war diaries. Produced by each regiment of the Canadian Army, these documents make it possible to follow their actions and activities. For example, the war diary of the Régiment de la Chaudière tells us that shortly after Marcel’s assignment on September 4, 1943, the order was given to move to Camp Shira, in Scotland, to carry out exercises in preparation for the landings. In the same month, the war diary describes the training and progress of the Régiment de la Chaudière’s four different companies, A, B, C and D, in reaching their targets, as well as incidents along the way.

The regiment’s war diary also includes regimental orders, which are precise enough to trace Marcel’s route at the time of the landings and during the Battle of Normandy, since they include his company and its movements. According to the regimental orders of September 1943, Marcel was assigned to D Company. On D-Day, Marcel was to remain on the landing craft until A and B companies had reached their objectives in the Nan White sector, before disembarking on the beach as reinforcements. To this end, the diary provides the training syllabus and describes the exercises carried out in preparation for the landing.

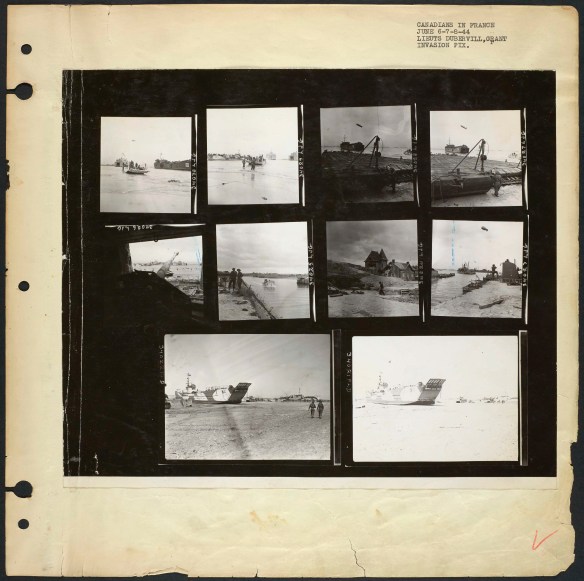

On June 6, 1944, Marcel embarked with D Company on the ship Clan Lamont, which was preparing to cross the English Channel. The last breakfast was served at 4:30 a.m. and then, by 6:20 a.m., everyone was aboard the ship that set off in turbulent seas toward Bernières-sur-Mer. Many were ill due to anxiety and seasickness. At 8:30 a.m., the Régiment de la Chaudière disembarked to join the fight in which the Queen’s Own Rifles Regiment was already engaged. But a storm the night before, which disrupted the tidal currents, combined with fierce resistance from the Germans, delayed the arrival and progress of the Queen’s Own Rifles. While they should have already taken Bernières-sur-Mer before the Régiment de la Chaudière arrived, they were trapped on the beach under enemy fire, unable to advance.

Detail from a map of the Juno Beach area (e011297133). The Régiment de la Chaudière landed in the Nan White sector at Bernières-sur-Mer.

Ultimately, the German defence gave way under pressure, allowing the Canadian Army to enter Bernières-sur-Mer and to secure the surrounding area. By day’s end, the companies of the Régiment de la Chaudière regrouped at Colomby-sur-Thaon, thus helping establish a bridgehead for the Allies in France. It was an important victory, but only the beginning of the Battle of Normandy, which would last for more than two months and claim many more lives.

Advances continued throughout the month of June. The Régiment de la Chaudière gradually approached the city of Caen to seize control of it. However, there was still one vital objective to conquer: Carpiquet. This village with its airfield had been fortified by the Germans, who relied heavily on it to resist the Allies. Taking Carpiquet and its airfield would be tantamount to dismantling the strategic point of the German air force closest to the Allies. It would also open the doors to the conquest of Caen.

The offensive on Carpiquet began on July 4 at 5:00 a.m. B and D companies were part of the first Allied assault group, advancing under cover of an enormous barrage provided by 428 guns and the 16-inch cannons of Royal Navy battleships HMS Rodney and HMS Roberts. However, the enemy’s defence was fierce. The Germans were better positioned and organized; they had even had time to fortify their positions with concrete walls at least six feet thick. That morning, they rained down a veritable deluge of artillery shells and mortar rounds. The first day’s action left many members of the Régiment de la Chaudière dead or wounded.

Briefing of Canadian infantrymen outside a hangar at the airfield, Carpiquet, France, July 12, 1944 (a162525). Taken after this vital point was seized, this photo reveals the ravages of this bloody battle.

On July 8, 1944, Marcel Gauthier was hit by shell fragments. The explosion left him with a serious head wound and his regiment quickly brought him to the nearest Canadian Army Medical Corps station. He was taken to the 22nd Canadian Field Ambulance, then sent to Casualty Evacuation Station No. 34, and was finally admitted to the 81st British General Hospital where, despite the personnel’s best efforts, he succumbed to his injuries on July 15, 1944. He was posthumously awarded the France and Germany Star for his service.

A soldier of the Régiment de la Chaudière who was wounded on July 8, 1944, during the battle for Carpiquet receives care from the 14th Field Ambulance of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (a162740). This is not Marcel Gauthier, but one of his fellow soldiers.

Marcel Gauthier is buried in lot IX.A.11 at the Bény-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery. His gravestone bears the inscription submitted by his father, Henri: “Our dear Marcel, so far away from us, we will always think of you resting in peace,” where his name liveth for evermore.

Additional resources

- The Life of Private Marcel Gauthier (Part 1), by Ariane Gauthier, Library and Archives Canada Blog

- Have you heard of Léo Major, the liberator of Zwolle?, by Gilles Bertrand, Library and Archives Canada Blog

- D-Day and the Normandy Campaign: June 6 to August 30, 1944, by Alex Comber, Library and Archives Canada Blog

- Census Search, database, Library and Archives Canada

- Canadian Virtual War Memorial, database, Veterans Affairs Canada

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission, database, Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Ariane Gauthier is a Reference Archivist with the Access and Services Branch of Library and Archives Canada.