By Emily Monks-Leeson

The subject of today’s post in our blog series, First World War Centenary: Honouring Canada’s Victoria Cross recipients, is one of the best-known Canadians of the First World War: flying ace William “Billy” Bishop.

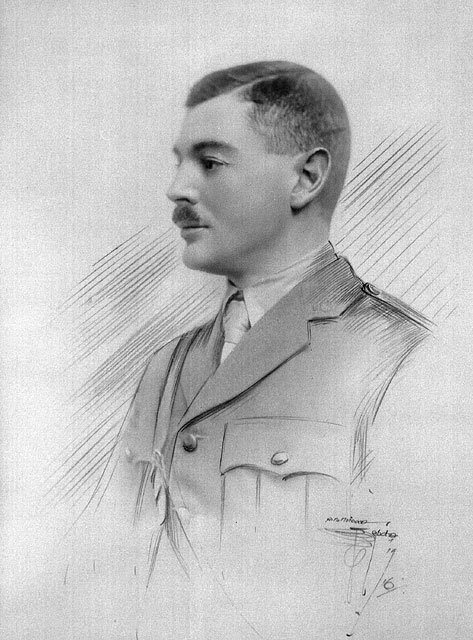

Lieutenant-Colonel W.A. Bishop, VC, in Lieutenant Quinn’s studio, undated, London, England (MIKAN 3191874)

William Avery Bishop was a cadet in the Royal Military College of Canada when he enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force on September 30, 1914. After briefly serving in the trenches, Bishop transferred to the Royal Flying Corps. He received his wings in November 1916, and shot down a total of 12 planes in April 1917 alone, which won him the Military Cross and saw his promotion to Captain. By the end of the First World War, Billy Bishop had been promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and was credited with 72 victories.

Captain W.A. Bishop, VC, Royal Flying Corps, August 1917. Photographer: William Rider-Rider (MIKAN 3191873)

Bishop was the first Canadian airman to be awarded the Victoria Cross for his single-handed attack on a German airfield near Cambrai, France, on June 2, 1917. According to his citation in The London Gazette:

Captain Bishop, who had been sent out to work independently, flew first of all to an enemy aerodrome; finding no machine about, he flew on to another aerodrome about three miles south-east, which was at least twelve miles the other side of the line. Seven machines, some with their engines running, were on the ground. He attacked these from about fifty feet, and a mechanic, who was starting one of the engines, was seen to fall. One of the machines got off the ground, but at a height of sixty feet Captain Bishop fired fifteen rounds into it at very close range, and it crashed to the ground.

A second machine got off the ground, into which he fired thirty rounds at 150 yards range, and it fell into a tree.

Two more machines then rose from the aerodrome. One of these he engaged at the height of 1,000 feet, emptying the rest of his drum of ammunition. This machine crashed 300 yards from the aerodrome, after which Captain Bishop emptied a whole drum into the fourth hostile machine, and then flew back to his station (The London Gazette, no. 30228, Saturday, 11 August, 1917).

Air Marshal William Avery Bishop died on September 11, 1956 in Palm Beach, Florida. He is interred in the Bishop family plot in Greenwood Cemetery in Owen Sound, Ontario.

Library and Archives Canada holds the CEF service file of William Avery Bishop.

Related Resources

- Personnel Records of the First World War Database

- William Avery Bishop fonds

- William Avery Bishop on The Canadian Encyclopedia

Emily Monks-Leeson is an archivist in Digital Operations at Library and Archives Canada.

![A black-and-white photograph of two men adorning a makeshift grave with white stones in a desolate landscape that has patches of snow and frost on the ground. The grave is marked by a cross with the words “L.S. [Lance-Sergeant] E.W. Sifton, VC” and adorned with a maple leaf. Beside the grave is a larger cross with the words “RIP Canadian soldiers killed in action 9-4-17.”](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/a0024151.jpg?w=584&h=453)

![A typewritten account of the actions that led to Lance-Sergeant Sifton’s Victoria Cross medal: “An act of conspicuous gallantry was performed by Sergt. E.W.Sifton of ‘C’ Coy [Company]. A M.G. [machine gun] was holding up his Company and doing considerable damage. Sergt. Sifton, single-handed, attacked the Gun crew and bayoneted every man, but was unhappily shot by a dying Boche.”](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/e0010994131.jpg?w=584&h=355)