By Ariane Gauthier

As part of my work as a reference archivist at Library and Archives Canada (LAC), I often find myself delving into the many documents in the Second World War collection. Many people around the world are interested in the history of Canadians in this conflict and, more specifically, in the experiences of our soldiers. What I find even more fascinating is how the quest begins for the researchers I am lucky enough to work with. The starting point is often a personal story, passed down in a family or a small community: “I found out that my mother served in the Royal Canadian Air Force” or “I heard that my village hid a Canadian spy during the Second World War.” This is enough to fuel the fire of researchers, who then dig to find evidence or fill in these stories with new details.

My colleagues and I participate in this quest on an ad hoc basis, mainly to facilitate access to documents from LAC’s vast collection. When circumstances allow, we delve into the information in these documents in search of relevant details that can help researchers piece together the story they seek to understand.

That is how I found three letters from Normandy addressed to our Canadian soldiers. Unfortunately, the context of the letters, including the identity of the recipient, remains a mystery. I found these letters in a file from Royal Canadian Air Force headquarters (Reference: R112, RG24-G-3-1-a, BAN number: 2017-00032-9, Box number: 30, File number: 181.009 (D0624)). This file documents the experiences of Canadian soldiers who were captured and interned in prison camps during the Second World War. It also contains transcripts of interviews about the soldiers’ experiences.

In this case, the three letters are not linked to specific interviews and are included in this file as loose sheets. There is no correspondence explaining why they were placed in this file. Nor is it known whether these were letters addressed to soldiers who had been taken prisoner during the war. The information in these letters is truly the only information we have. In reality, though it may not seem like much, these three letters tell us a great deal about the experience of soldiers in Normandy and of the French, especially the risks faced by those who resisted the Germans.

Here are the letters in question:

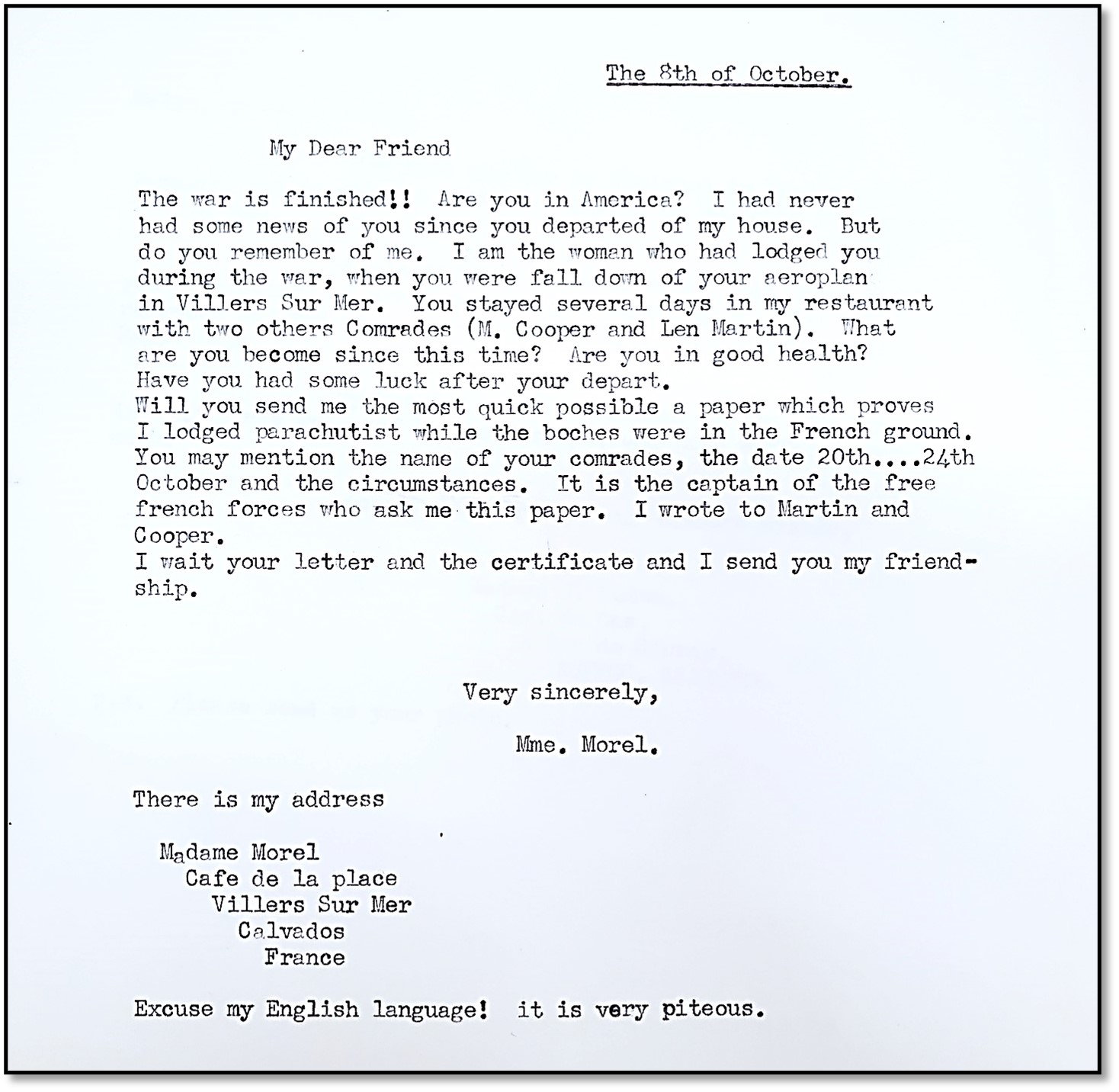

Letter to a Canadian soldier from Mrs. Morel, dated October 8 (MIKAN 5034948)

In this first letter, we discover part of the story of Mrs. Morel, who apparently sheltered one of our soldiers after he jumped from a plane near Villers-sur-Mer. We learn that this soldier was a paratrooper and that he had taken refuge in Mrs. Morel’s restaurant with two of his fellow soldiers, M. Cooper and Len Martin, while the village was still under German occupation.

Letter to a Canadian soldier from Mrs. J. Cottu (MIKAN 5034948)

This second letter gives us a glimpse into the story of Mrs. J. Cottu and could possibly be related to that of the paratrooper mentioned in Mrs. Morel’s letter. Without more specific information, it is difficult to confirm this hypothesis, but the second letter refers to a Sergeant Martin (possibly Len Martin?) and places his departure in November. Mrs. Morel stated that she had taken in the soldier at the end of October, without specifying the year, so everything could fit together chronologically.

Mrs. J. Cottu mentions having housed three soldiers in her house in Ruffec in November 1943: the recipient of the letter, Sergeant Martin and Captain Ralph Palm. Although this story seems to have gone well, she said that she was arrested by the Gestapo in 1944 because of her husband’s activities. The seriousness of the situation is clear from this confession: “I was arrested by the Gestapo, and have suffered very much.”

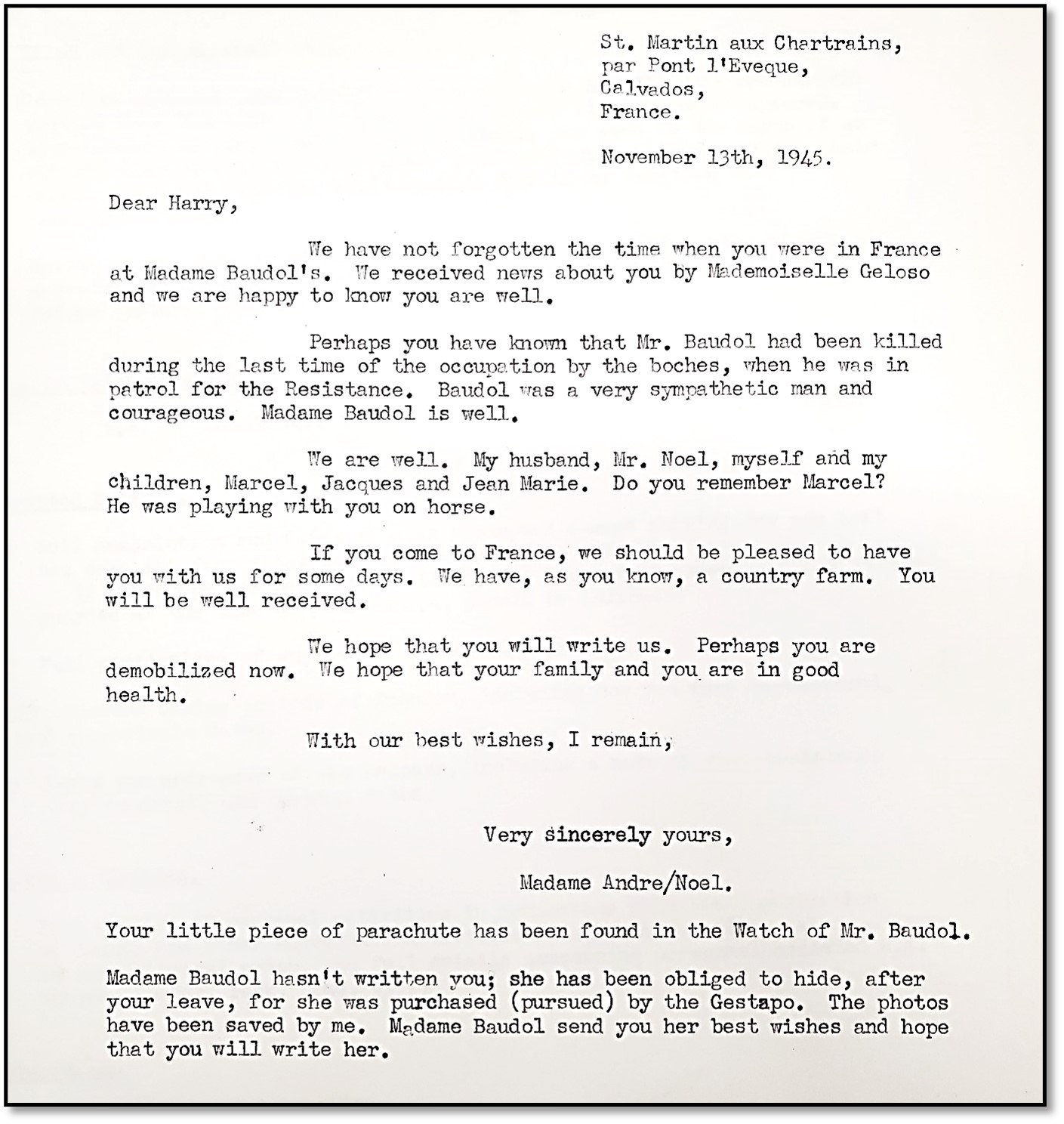

Letter to Harry from Mrs. Andre Noel, dated November 13, 1945. (MIKAN 5034948)

In this third letter, Mrs. Noel clearly illustrates the dangers that members of the Resistance faced. She bears the burden of announcing the death of Mr. Baudol, a member of the Resistance, who was killed while on patrol. She also shows us the strong bonds that Harry seems to have formed with the residents of Saint-Martin-aux-Chartrains. Although this letter expresses suffering, grief and fear, it also highlights the bravery and sacrifice of three families who came to the aid of a Canadian soldier.

Ariane Gauthier is a reference archivist with the Access and Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.