By Andrew Elliott

In the first post of the Black Porter Perspectives series, Rebecca Murray highlighted a wartime photograph that identified a railway sleeping car porter: Jim Jones of Calgary. In the Canadian National (CN) fonds, with which I work, it is worth noting that finding a porter’s name is rare. This collection (RG30/R231), one of Library and Archives Canada’s (LAC) largest private acquisitions, should logically contain a plethora of records about porters due to their central role in railway service. Sadly, until recently, this has not been the case. A basic keyword search for “porter” often yielded few, if any, results. I am working hard to correct this situation.

Over the last few months, my work has involved sifting through backlogged material relating to the CN Passenger Services Department. I recently found a collection of files from the late 1960s documenting employees who worked for the CN Sleeping, Dining, and Passenger Car Department. These files cover a range of issues, including accidents, insurance claims, thefts of company property, and retirements, as well as provide insight into the lives of cooks, waiters, stewards, and porters. Among these, I discovered an important and interesting personnel file for a Black porter named Mr. Thomas Nash. His file stood out due to his remarkable 42-year career, spanning from his hiring on June 23, 1927, to his retirement in August 1969. This documentation sheds light on who Nash was and offers a deeper understanding of what portering looked like for him and other Black men during this period.

Who was Mr. Thomas Nash?

Nash’s personnel file is rich with details, allowing us to begin to piece together his biography. Raised by his adoptive parents in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Nash later moved to Montréal, where he worked as a CN porter. The path to learning this information is particularly interesting.

In the late 1940s, CN’s Staff Record Bureau began seeking Nash’s birth date to determine his retirement eligibility. Like many Black citizens in Canada and the United States, Nash faced challenges with recordkeeping, which were compounded by his adoption. He offered several possible birth years, including 1899, 1900, 1902, 1904, 1905, and 1907, which further complicated the Bureau’s task.

Documentation from the CN Staff Record Bureau detailing various possible birth dates for Thomas Nash, dated June 10, 1952. (MIKAN 6480775)

Due to Nash’s inability to provide accurate information about his birth, the CN Bureau contacted the principal of St. Ninian School in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, which Nash had attended as a youth. This inquiry in 1952 proved unsuccessful. The following year, the CN Bureau contacted the Dominion Bureau of Statistics, which confirmed that Nash had actually been born on August 26, 1904. The 1911 Census further revealed that Nash lived with his adoptive parents in Antigonish, a detail that is recorded in his personnel file. Interestingly, while his personnel file does not address the matter explicitly, Nash’s last name appears to have changed between his youth and his move to Montréal. As a child, he went by the surname “Ash,” which later became “Nash” before he began his job with the CN. Was this a recording error? Determining his correct birth details led to Nash’s eligibility for the CN Pension Plan, which went into effect on January 1, 1935.

In addition to learning a little bit about his early life, we also see that upon relocating to Montréal, Nash became part of the city’s tight-knit Black community, living in what was then known as the St. Antoine District. This is unsurprising given the racial segregation in housing and the community’s proximity to the train station.

While his early years in Montréal are undocumented in his personnel file, we see that Nash resided at 729 Seigneurs Street in the 1950s and early 1960s. A 1968 letter he wrote to the CN Staff Record Bureau reveals that he had married and later resided with his wife at 2458 Coursol Street, just a few streets over from his former residence.

Nearly every household in the St. Antoine District had ties to portering. This profession was deeply respected, as evidenced by a community ritual honouring retiring porters: family, friends, colleagues, and bosses gathered at the train station to welcome these men home from their final runs. The Black Worker, the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters’ union newsletter, often documented these special moments. Nash undoubtedly experienced such recognition when he retired in 1969.

Letter detailing Thomas Nash’s upcoming retirement in August 1969. (MIKAN 6480775)

The rights and experiences of porters

Nash’s career began in 1927, a pivotal year for both CN and its employees. That year, CN and its union, the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees (CBRE), created a segregated system dividing employees into two groups. Group 1 included dining car employees and sleeping car conductors (white men), while Group 2 consisted of sleeping car porters. These separate collective agreements restricted seniority and promotion opportunities within each group, effectively locking Black workers into portering and barring them from advancing within CN’s ranks.

Nash would have quickly realized that upward mobility was impossible for him. Dr. Steven High helps us contextualize Nash’s experience, noting that porters in the 1920s and 1930s worked very long hours with a fixed monthly salary, regardless of the actual number of hours worked. On average, porters were allowed just three hours of sleep per day while in transit. Needless to say, their working conditions were difficult and highly exploitative. Unfortunately, Nash’s early years on the job, including his contributions during the Second World War, are undocumented in his personnel file—a troubling omission given the essential nature of his work.

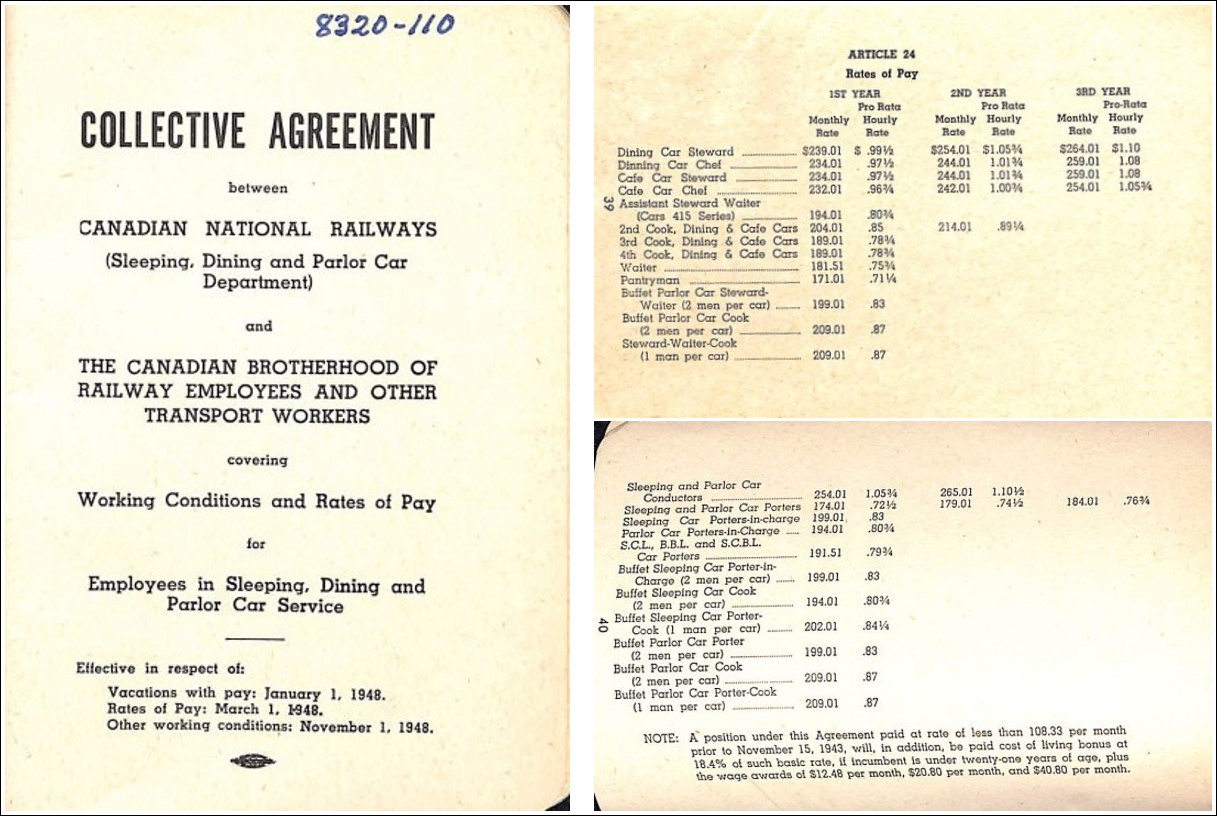

Despite their invisibility in these records, Black porters began agitating for improved conditions. In 1945, Canadian Pacific Railway sleeping car porters successfully negotiated a new collective agreement that including better wages, vacation time, and reduced hours. These union gains, however, did not extend to CN employees who remained bound by CBRE’s more restrictive agreement. The agreement featured below, dated 1948, shows that all porters remained among the lowest-paid employees, second only to pantrymen, with monthly salaries ranging between $174 to $209. Also, unlike some of the other occupations listed, porters’ salaries would not increase in years two or three. In truth, these men saw little improvement to their working conditions until 1964, when the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway, Transport and General Workers came into existence, ending occupational colour barriers and creating a combined seniority list.

(For more information about the long fight for porters’ rights, listen to “Porter Talk: The Long Fight for Porters’ Rights.”)

Pages from the 1948 CBRE Collective Agreement, covering working conditions and rates of pay for employees in sleeping, dining, and parlour car service. (MIKAN 1559408)

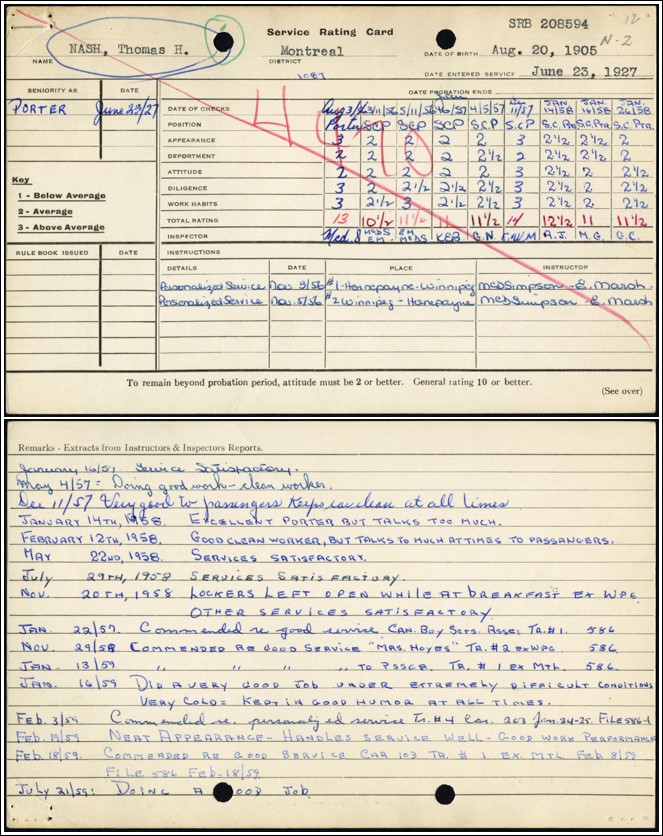

A cursory engagement with the CN fonds might obscure the contribution of porters, but Thomas Nash’s personnel file provides valuable insight into the nature of their work. His employee service rating card, in particular, emphasized the stresses inherent in portering. This card was designed to document and rank the quality of service provided, a reminder that Nash and his colleagues were under constant scrutiny—whether by CN staff or passengers. It is interesting to point out that even minor infractions could result in demerit points, colloquially known as “brownies.” Accumulating 60 demerit points led to automatic termination without the possibility of appeal. Remarkably, Nash’s record stands out: in his 42-year career, he never incurred a single demerit point. The comment card below showcases a passenger’s remark from 1958, providing a vivid anecdote and serving as a testament to Nash’s exceptional service: “Excellent Porter but talks too much.” While seemingly contradictory, this remark sheds light on Nash’s engaging personality and unwavering commitment to his duties.

Front and back of Thomas Nash’s employee service rating card. (MIKAN 6480775)

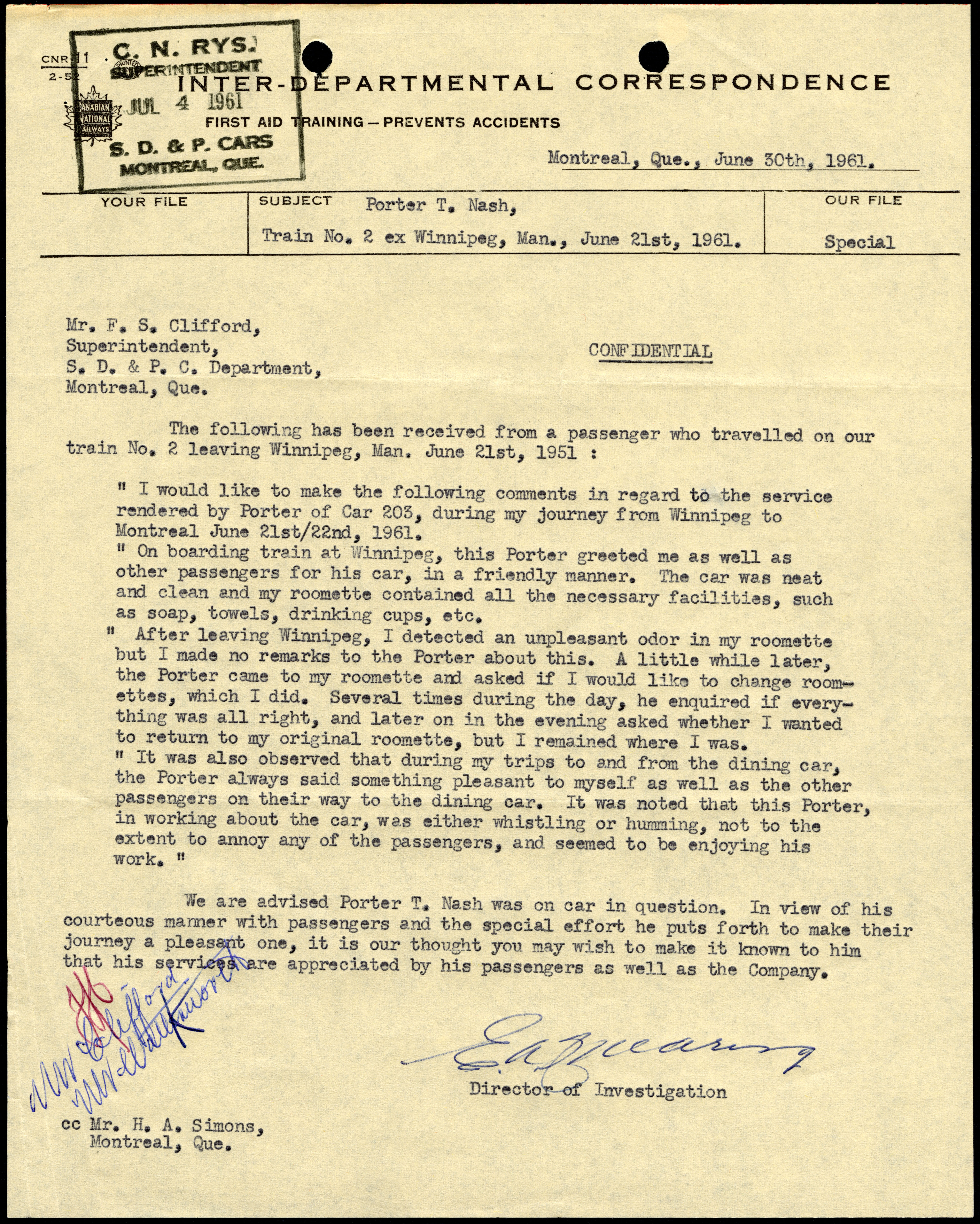

In 1961, another passenger went further, commending Nash for his service:

Letter documenting a passenger’s commendation of CN porter Thomas Nash for service excellence, 1961. (MIKAN 6480775)

Making porters’ service visible

My team remains committed to uncovering more information about the lives porters led and the experiences they had on the rails. Since last year, we have uploaded over 21 000 service files related to employees who worked for CN and its predecessor companies—including records for 1 066 porters—to the series entitled Employees’ provident fund service record cards. Slowly but surely, we are uncovering records within the CN fonds that shed light on the invaluable contributions of porters, making their essential service visible. In many ways, this work allows us to honour their legacy and bring their stories back to life, contributing to a new understanding of their profound impact in shaping modern Canada.

Andrew Elliott is an archivist in the Archives Branch at Library and Archives Canada.