By Isabelle Charron

This article contains historical language and content that may be considered offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

First page of the journal of John Norton (item 6251788)

Portrait of John Norton by Mary Ann Knight, 1805 (e010933319)

Library and Archives Canada (LAC) recently acquired an unpublished autograph journal by John Norton (Teyoninhokarawen) (1770–1827), along with letters (John Norton Teyoninhokarawen fonds*). This acquisition was made possible by a contribution from the Library and Archives Canada Foundation. The journal’s existence was documented in correspondence from the early 19th century, but its location remained unknown until recently. These documents are an important link in the life and literary production of Norton, a fascinating character, as well as essential evidence for understanding the history of the Six Nations (Haudenosaunee), Canada and North America.

Born in Scotland, Norton had Indigenous ancestry: his father was Cherokee, brought to Great Britain by a British officer following the Anglo-Cherokee War, and his mother was Scottish. His family background shaped his astonishing journey. In addition, he was marked by military life from a very young age. His father, a soldier in the British army, took part in several campaigns in North America, during which his family followed him. In fact, Norton mentions in a letter that one of his earliest memories was the Battle of Bunker Hill (Boston, June 17, 1775) (item 6252667). Back in Scotland at an unknown date, he received an excellent education.

Norton and his parents were in the city of Québec in 1785. Like his father, he joined the army, but he deserted in 1787 at Fort Niagara. He later travelled and may have lived with the Cayuga Nation. In 1791, he worked as a schoolteacher in the Mohawk community of Tyendinaga (Bay of Quinte, Ontario). He then took part in battles in the Ohio Valley with various allied Indigenous peoples against American forces. He was also involved in the fur trade for Detroit merchant John Askin before being hired as an interpreter by the Department of Indian Affairs. He then lived with the Six Nations (Haudenosaunee) at the Grand River (Ontario) and became close to Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea). The latter adopted him as a nephew in 1797, and in 1799 Norton became chief for diplomacy and war for the Six Nations. He was given the Mohawk name of Teyoninhokarawen.

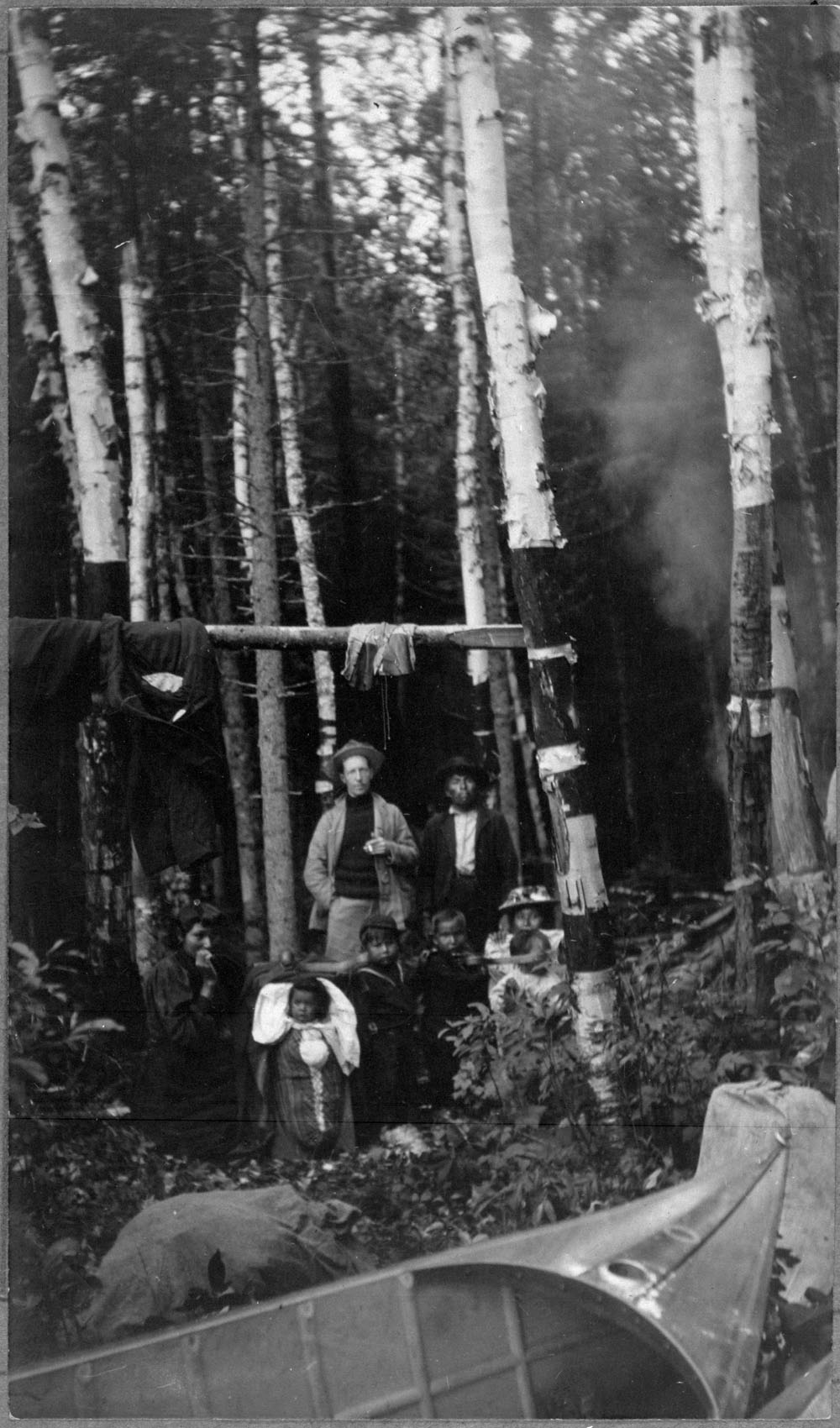

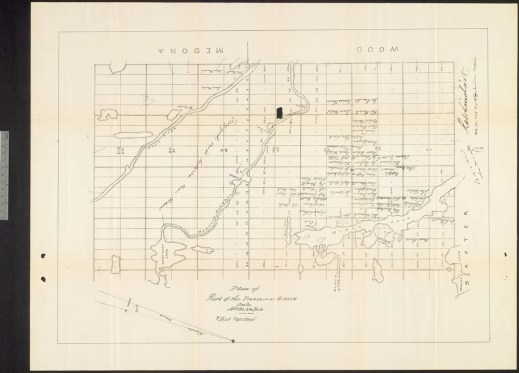

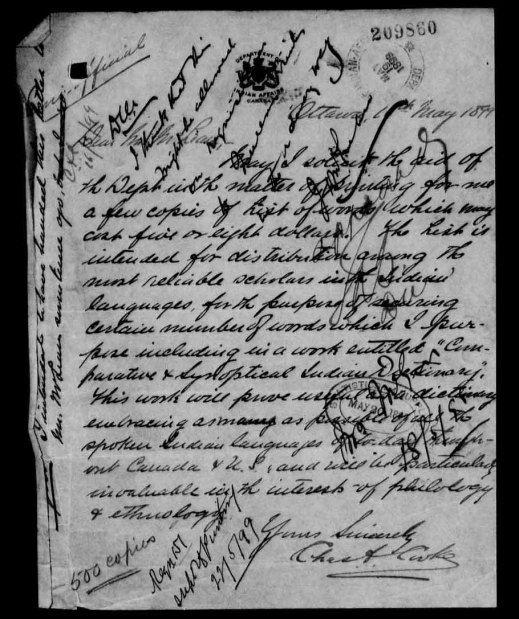

The Norton journal acquired by LAC is 275 pages long (item 6251788). He wrote it at the Grand River between 1806 and 1808 in the form of letters to a friend. He recounts his journey to England and Scotland in 1804–1805. It was at Brant’s request that he made this trip to clarify issues relating to Six Nations land ownership at the Grand River, in connection with the Haldimand Proclamation (October 25, 1784). His diplomatic mission failed because his authority was challenged by some, including William Claus, superintendent of Indian Affairs. However, on a personal level, Norton was able to reconnect with his maternal family and became a very popular figure among the political, business, religious, intellectual and aristocratic elite. He participated in social events and attended scientific conferences and debates in the House of Commons. He made valuable friends, including the brewer Robert Barclay, the Reverend John Owen and the second Duke of Northumberland (Hugh Percy), also a friend of Brant. During this time, Norton translated the Gospel of John into Kanien’kehá (Mohawk language), published by the British and Foreign Bible Society as of 1804 (OCLC number 47861587). In London, in 1805, artist Mary Ann Knight painted his portrait, now in LAC’s collection (item 2836984).

Pages 183–185 of the journal of John Norton (e011845717)

In 1808, Norton sent his journal to Robert Barclay in England, who planned to publish it with the accompanying letters. This project, on which the Reverend Owen also worked, never materialized, and the documents remained in the Barclay family. In his journal, Norton describes his encounters and the places he visited. He expresses his thoughts on a variety of topics typical of his era and touching on colonial reality, such as the British army, American independence (and its consequences for Indigenous peoples on both sides of the border), freedom, slavery (he is an abolitionist), education, the status of women among Indigenous people, agriculture, trade (including the fur trade), business and land exploration. He plans several projects for the Haudenosaunee and is concerned about the education of young people. He questions the image of the Haudenosaunee portrayed by certain authors and insists on the refinement of their language. Christianity is also of great importance to Norton.

Norton’s correspondence reveals some details about his biography and his family (items 6252667 and 6258811). In it, he recalls his return to the Grand River in 1806, divisions in his community and his desire to take part in campaigns with the British army (item 6251790). He speaks about different Indigenous peoples and their relationships with British colonial authorities (items 6251794 and 6252528, for example). He promotes the alliance between Indigenous peoples and Great Britain but is very critical of the Department of Indian Affairs. This alliance proved essential in the War of 1812, during which Norton distinguished himself by leading groups of Indigenous warriors. He refers to this conflict in his letters (item 6258793), as well as his visit to the Cherokee in 1809–1810 (item 6258679). The correspondence also includes a transcript of a letter from chiefs of the Six Nations to Francis Gore, lieutenant governor of Upper Canada (item 6252665). Finally, a letter from someone close to Barclay confirms that George Prevost, governor-in-chief of British North America, held Norton in high regard (item 6258814).

It should be noted that Norton wrote a second journal while in England in 1815–1816, which covers his visit to the Cherokee, the War of 1812 and the history of the Six Nations. Still preserved in the Archives of the Duke of Northumberland at Alnwick Castle in England, this journal was published in 1970 and 2011, and the War of 1812 section was also published in 2019 (see references below).

A great traveller, polyglot, author, translator, letter writer, diplomat, politician, warrior, activist, trader, farmer, father, Scotsman, Cherokee, Haudenosaunee … so many epithets characterize John Norton, who already fascinated people during his lifetime. He is said to have been the inspiration for the main character in John Richardson’s 1832 novel Wacousta, a Canadian literary classic. Richardson had known Norton and was the grandson of John Askin, the fur trader for whom Norton had worked in his youth.

We hope that these newly acquired documents, which are important additions to our collection, will generate much interest and shed new light on Norton’s life and work, as well as on the history of the Haudenosaunee and Canada in the early 19th century.

Happy exploring!

To learn more

- Alan James Finlayson, “Emerging from the Shadows: Recognizing John Norton,” Ontario History, vol. 110, No. 2, fall 2018.

- John Norton, A Mohawk Memoir from the War of 1812: John Norton—Teyoninhokarawen, Carl Benn, ed., Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2019 (OCLC 1029641748).

- John Norton, The Journal of Major John Norton, 1816, Carl F. Klink, James J. Talman, ed., introduction to new edition and additional notes by Carl Benn, Toronto, The Champlain Society, vol. 72, 2011 (1970) (OCLC 281457).

- Carl F. Klinck, “Norton, John,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003 (1987).

- Cecilia Morgan, Travellers Through Empire: Indigenous Voyages from Early Canada, Montréal & Kingston, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017 (OCLC 982091587).

- Guest Curator: Shane McCord, Library and Archives Canada Blog, posted on September 14, 2017.

*Since these documents were created in English, their individual descriptions are also in English.

Isabelle Charron is a Senior Archivist in the Private Archives and Published Heritage Branch at Library and Archives Canada.

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/blog-banner.jpg)

![On the left of the graphic, Tatânga Mânî [Chief Walking Buffalo] [George McLean] in traditional regalia on horse. In the middle, Iggi and girl engaging in a “kunik”, a traditional greeting in Inuit culture. On the right, Maxime Marion, a Métis guide stands holding a rifle. In the background, there is a map of Upper and Lower Canada, and text from the Red River Settlement collection.](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/blog-banner-1.jpg)