By Dylan Roy

“Get on your bike and ride,” my mother often told me in my youth when I would ask for a lift somewhere. Although I would sometimes begrudge her for forcing me to stay active (being the indolent child that I was), looking back, I am glad that I biked to the places I needed to go in my teenage years. Biking provided not only exercise, but also a form of agency and sorely needed sociability.

On reflection, cycling is a virtually ubiquitous phenomenon wherever people live. It came to me as a surprise that even the Canadian military used cycling. I just didn’t think of the reasons why they would. To me, it seemed like a far-fetched thing and an activity in which only civilians partook. However, the Canadian military has implemented the use of cyclists within its ranks throughout much of its history.

This series will focus on the military units who used bicycles as one of their primary duties during their service. The first entry into this series will focus explicitly on the divisions that served during the First World War. So, strap on your helmet and start peddling down the road of the following paragraphs to learn more about the brave bikers who served in our military during the Great War.

Panoramic photograph of the 2nd Division Cycle Corps, Canadian Expeditionary Force. (e010932293)

Before starting, it is important to highlight that Library and Archives Canada (LAC) offers a wide variety of resources to find information concerning the cyclist divisions, companies and Corps that took part in the First World War. One of the handiest is the Guide to Sources Relating to Units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force: Cyclists. This guide can inform a researcher about many aspects of the cyclist units. However, be warned: there are some transcription errors mentioned in the preface to the guides on the Sources Relating to Units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force page. They are, nonetheless, valuable tools for research.

Outside of LAC, the Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War: Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919 is another secondary source that can provide important information concerning the cycling units.

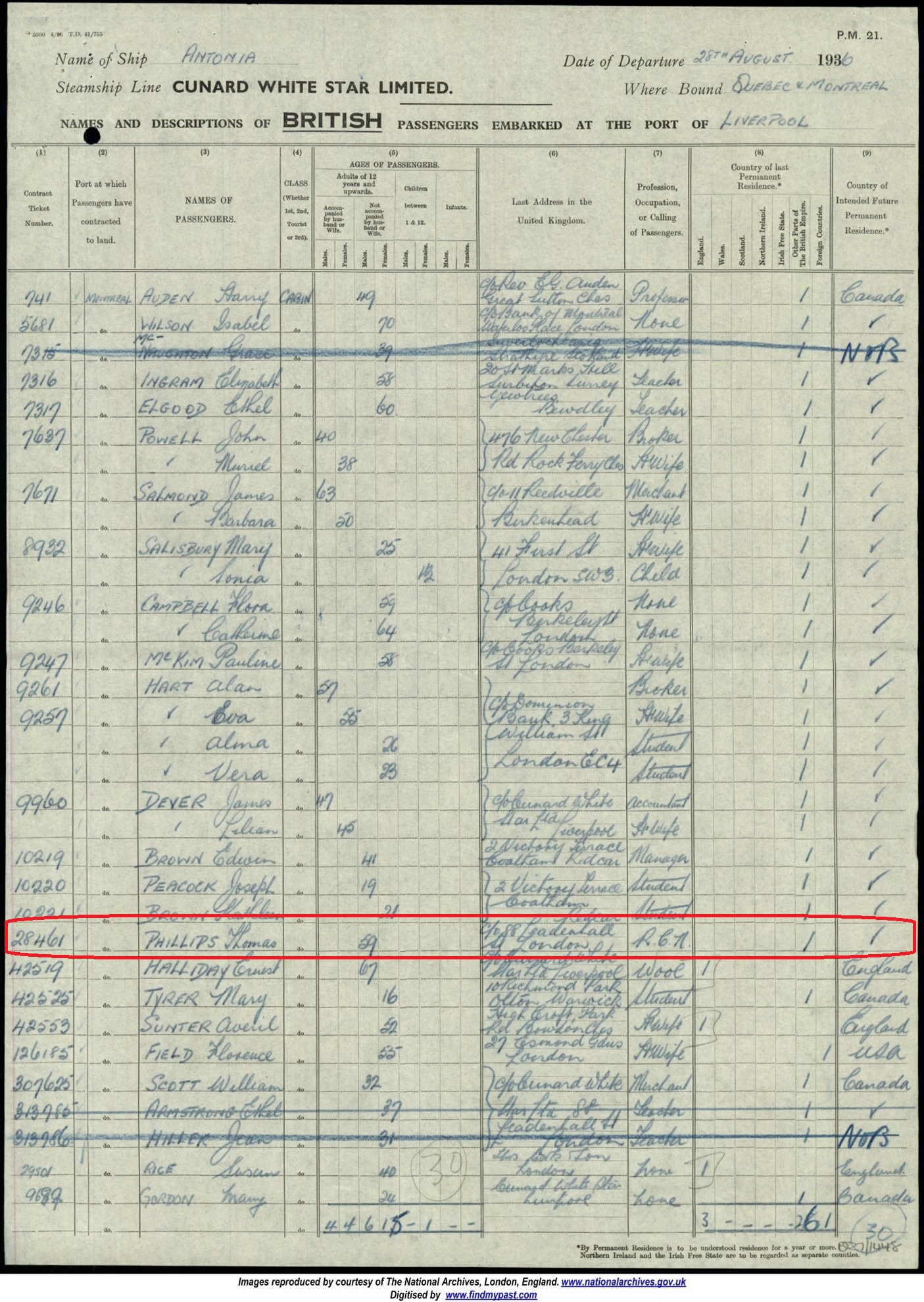

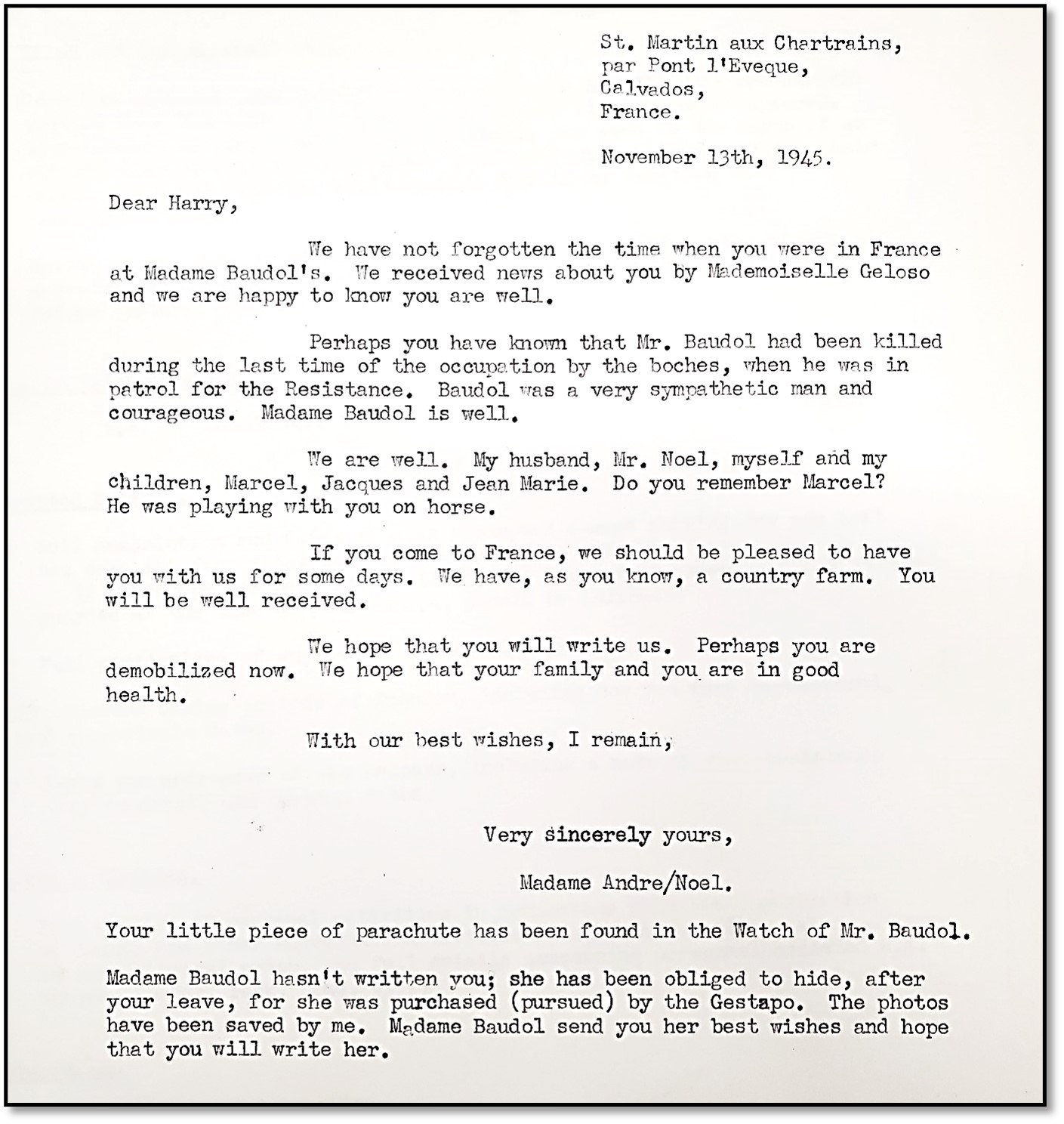

With that out of the way, what did the cyclist units actually do during the war? The Canadian Encyclopedia provides this succinct summary of the cyclist units: “In WWI young men with the cycling urge were encouraged to join the Canadian Corps Cyclists’ Battalion. Over 1000 men eventually did so, their duties ranging from message delivery and map reading to reconnaissance and actual combat.”

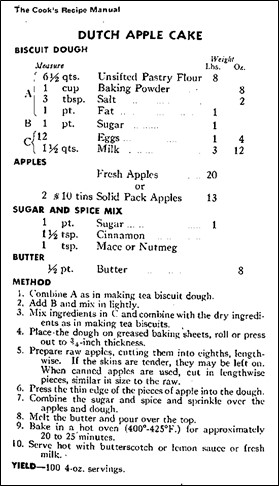

Moreover, since our troops were equipped with bicycles, it meant that they were relatively mobile compared to infantry units. They were therefore considered “mounted” and, in fact, fell under the same umbrella as the Canadian Light Horse regiment. When they said “get off your high horse,” the cyclist units took it very seriously. You can see where the cyclists fell in the military hierarchy with the 1918 Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) organization chart below:

Two screenshots of the 1918 Canadian Expeditionary Force organization chart. Full chart is displayed on top and the section which highlights the Canadian Corps Cyclist Battalion below. (Government of Canada website)

Although the cycling units were actively involved in the war, they first needed to be trained. LAC has a variety of videos on YouTube focusing on the Canadian military, including one that features some of the training aspect of the cyclist units titled The Divisional Cyclists : A Glimpse of a Day’s Training (1916).

The video demonstrates the importance of many topics, such as the more mundane aspects of military life (like laundry), while also shedding light on more crucial elements of training, such as drills, signalling and reconnaissance.

Four scenes from the video The Divisional Cyclists : A Glimpse of a Day’s Training (1916) demonstrating signalling, drill and reconnaissance training initiatives. (ISN 285582)

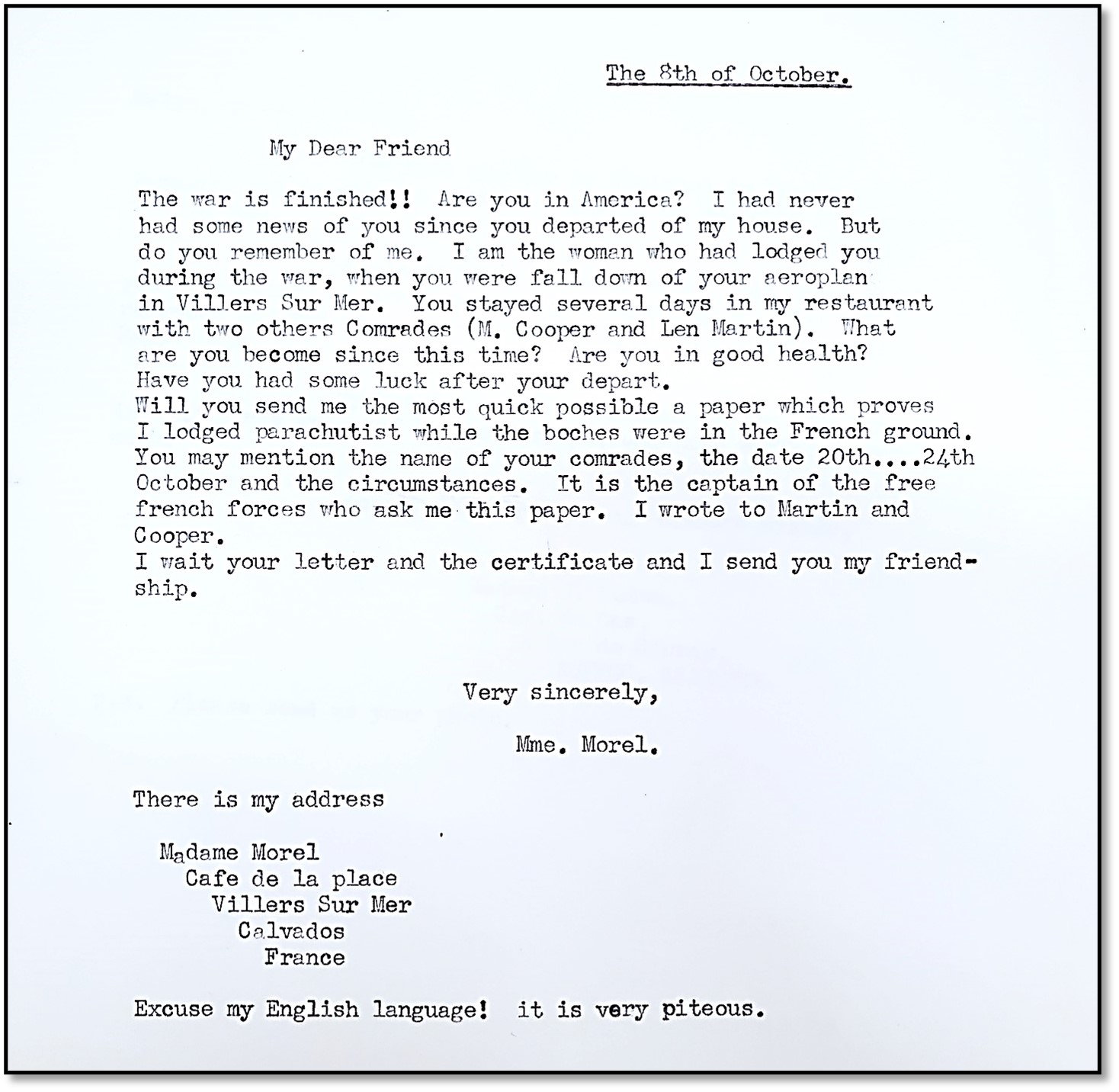

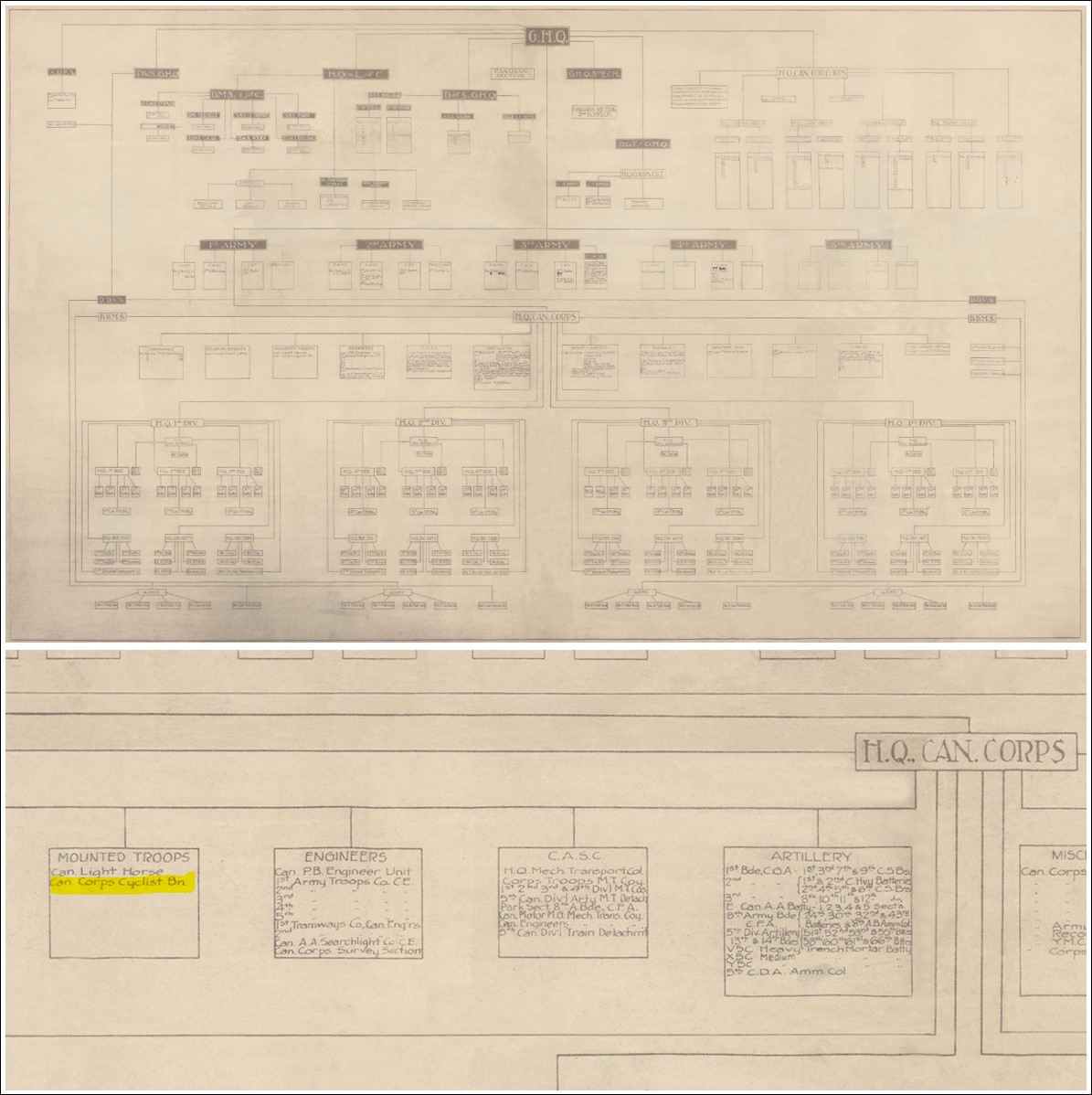

Once the cycling units had completed their training, they could partake directly in the war efforts. Our hardworking biking men-at-arms were no strangers to conflict, and they were part of some of the most notable battles of the First World War such as Ypres and Vimy. The following entry below from a war diary by the 1st Canadian Divisional Cyclist Company covers the horrific aspects of the battle of Ypres and how the division was involved on April 22nd, 1915, near Elverdinghe:

Terrific bombardment started on the front immediately EAST of here about 4:30 P.M. The whole line appeared to be enveloped by cloud of greenish smoke. At 6:30 P.M. requested arrival of many stragglers of the South African troops from the first line trenches all in a state nearing on collapse complaining of a new and deadly gas which had been wafted from the enemy’s trenches by a gentle NORTH-EAST wind, orders were given to D.M.T. to “stand-to.” At 7:15 orders came from DIV. H.Q. to proceed with all possible speed to there, which place was CHATEAU DES TROIS TOURST. Cyclists were ordered to “stand to” on the avenue leading to the ELVERDINGHE – YPRES road. Communication being down with various infantry, and artillery units of Division H.Q. from time to time asked for orderlies from the cyclists to report to different BRIGADE H.Q. as despatch riders. At 10:10 P.M. LIEUT. CHADWICK and No 1 Platoon were sent on a reconnoitering patrol on our immediate front across the canal. Corpl WINGFIELD with his section was despatched as a reconnoitering patrol behind the trench lines on our left.

Screenshot of War diaries – 1st Canadian Divisional Cyclist Company / Journal de guerre – 1re Compagnie divisionnaire canadienne de cyclistes. (e001131804, image 53)

The entry highlights the chaos of war and the hardships that many men suffered on that fateful day in April 1915. It also shares some of the more haunting aspects of the First World War, such as the use of gas described as green clouds of smoke. Additionally, it provides insight into some of the main tasks accomplished by the cyclists including communication, acting as despatches and reconnaissance.

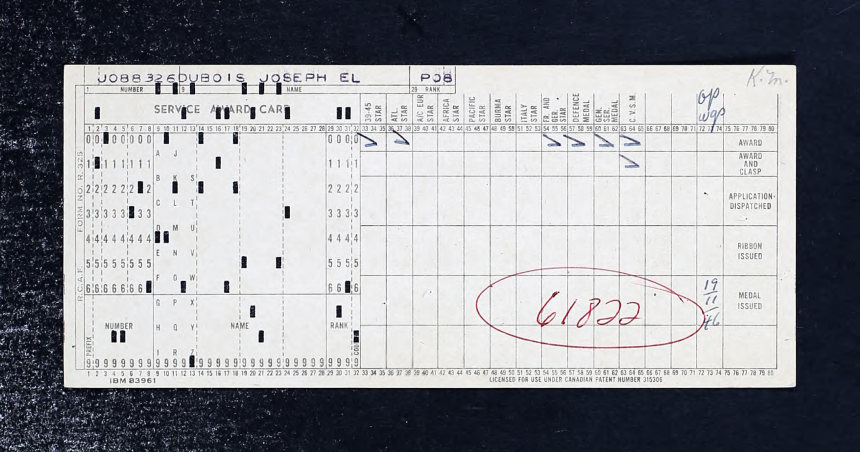

The cyclist divisions continued to expand during the war and, as highlighted earlier, an entire battalion was eventually formed called the Canadian Corps Cyclist Battalion. At LAC, there is an entire sub-series devoted to this battalion that shares further information in the Biography/Administrative history section on how it was formed and eventually disbanded. It reads:

The Canadian Corps Cyclist Battalion was organized at Abeele in May 1916 under the command of Major A. McMillan, and was formed by amalgamating the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Canadian Divisional Cyclist Companies. The battalion was demobilized at Toronto in April 1919 and was disbanded by General Order 208 of 15 November 1920. In Canada Cyclist Companies advertised for recruits “possessing more than average intelligence and a high standard of education.” (MIKAN 182377)

By viewing the lower-level descriptions from this sub-series, one can see records that pertain to the battalion. The sub-series includes a variety of topics such as a training syllabus of the reserve cyclist company and statements by Canadian prisoners of war (among others).

Photograph of officers in the Canadian Corps Cyclist Battalion from January 1919. (PA-003928)

The Canadian cyclist units were no slouches, and they had a definitive impact on the war effort by facilitating reconnaissance, communication, signalling and direct combat. It is impressive to think that these men, who used very archaic forms of bicycles were able to tread the perilous terrain of Europe during the First World War to accomplish their duties while I, using a much better modern bike, complain about having to bike up a small hill on my way to work. It shows how much determination and bravery the men within the cyclist units of the Canadian military exerted during the First World War.

Additional Sources

- Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War: Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919

- Canadian Encyclopedia: Bicycling

- 1918 Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) organization chart

Dylan Roy is a reference archivist in the Access and Services Branch at Library and Archives Canada.