By Jill Delaney

When Howard “Fred” Lambart’s (1880–1946) painful, frozen feet finally touched solid ground again on July 4, 1925, he thought he would feel elated. After all, it had been 44 days since he and his fellow mountaineers had made contact with anything other than snow and ice on their ascent of Mount Logan, Canada’s highest peak (5,959 m). The expedition had exhausted them all, and Lambart could only manage a sense of relief at having made it this far. There were still 140 kilometres of hard travel to go before they reached the town of McCarthy, Alaska.

Photograph of the party taken by Captain Hubrick at McCarthy, Alaska. From left to right: N.H. Read, Alan Carpe, W.W. Foster, A.H. MacCarthy, H.S. Hall, Andy Taylor, R.M. Morgan, Howard “Fred” Lambart (e011313489_s1).

Lambart was part of a team of eight climbers assembled by the Alpine Club of Canada and the American Alpine Club in 1925 to tackle Mount Logan, located in the remote southwestern corner of Yukon Territory, in what is now Kluane National Park and Reserve. The mountain is in the Tachal Region of the Kluane First Nation’s traditional territory, “A Si Keyi.” The Lu’an Mun Ku Dan (Kluane Lake People) and the Champagne and Aishihik peoples have lived there for generations.

Most Lu’an Mun Ku Dan, Champagne and Aishihik First Nations people identify themselves as descendants of the Southern Tutchone. Others came from nations such as the Tlingit, the Upper Tanana and the Northern Tutchone. In the Southern Tutchone language, the indigenous peoples of this region are known as “the people who live beside the tallest mountains.”

Lambart had climbed many of the peaks surrounding Mount Logan as a surveyor for the Geodetic Survey of Canada. As part of this work, he had conducted photo-topographic work on the Yukon–Alaska border in 1912–1913.

No European settler had yet attempted to conquer the behemoth that is Mount Logan, the most massive mountain in the world. It was and still is a remote sub-arctic mountain, with notoriously terrible weather due to its proximity to the west coast. The 1925 climbing team, made up of Lead Captain A.H. MacCarthy, Assistant Lead Fred Lambart, Alan Carpe, H.S. Hall, N.H. Read, R.M. Morgan, Andy Taylor and W.W. Foster, hiked 1,025 km in 63 days. They carried packs of up to 38 kilograms for most of this time, and climbed a total of 24,292 metres, or more than four times the elevation of the mountain, in order to transport their supplies up the mountain themselves. Thanks to the Lambart Family Fonds at Library and Archives Canada (LAC), containing both Lambart’s personal diary and over 200 photographs taken during the expedition, we have a detailed and intimate account of the thrills and extreme hardships of this remarkable climb. Alan Carpe also created a documentary film, The Conquest of Mount Logan. It is a fitting time to revisit the event, with the recent completion of the first of two ascents in 2021–2022 by Dr. Zac Robinson, Dr. Alison Criscitiello, Toby Harper-Merrett and Rebecca Haspel, from the Alpine Club of Canada and the University of Alberta. Using photographs from the 1925 expedition, they are conducting a repeat photography project, as well as an ice-coring project, to better understand climate and change.

Fred Lambart came from an upper-middle-class British-Canadian family, and graduated from McGill University with a bachelor’s degree in science. He initially worked on surveys for the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, before becoming a Dominion Land Surveyor in 1905. His daughter Evelyn would go on to an illustrious career as a filmmaker at the NFB. His daughter Hyacinthe was an early female Canadian pilot. Tragically, his two sons, Edward and Arthur, were killed during the Second World War.

The 1925 Mount Logan expedition came during a period of very active mountaineering, when Europeans saw “conquering” summits as moments of national, colonial and imperial prestige. Several attempts to summit Mount Everest were made during this time. In 1897, the Italian alpinist the Duke of Abruzzi (reportedly having his packers carry his brass bed up the mountain for him) summited Mount St. Elias, the second-highest peak in the Canadian northwest. Lambart himself was recorded as the first European to summit Mount Natazhat (4,095 m), in 1913.

Preparations for the 1925 Mount Logan expedition began in 1922. They included fundraising and the selection of the team. All agreed that A.H. MacCarthy should lead, with Lambart named as assistant. MacCarthy scouted three different routes in the years leading up to the official expedition, returning to the mountain again in February 1925 to cache 8,600 kilograms of supplies in advance, at various points along the route.

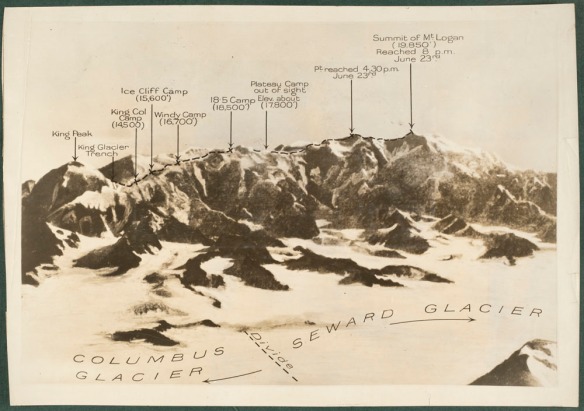

Annotated photograph showing the route of the 1925 expedition (e011313492).

The team leaves McCarthy, Alaska, on May 12 and begins its climb on May 18. Much of the ascent is taken up with grinding slogs by the team members (they have no packers once they step foot onto the mountain) relaying their supplies up and down the glaciers to their various camps. Nevertheless, the alpinists do find moments to note the incredible beauty of their surroundings. On June 6, Lambart writes, “the early morning lighting on the mountains and lakes on the day developing into one of perfect clearness was a vision not to be forgotten.”

By June 11, while camping at King Col (5,090 m), the climbers’ exertion is beginning to show, along with signs of elevation sickness amongst a few of the members. Lambart reports shortness of breath, and Morgan and Carpe both vomit during the night, while MacCarthy’s eyes begin to suffer. “If Mac doesn’t let up there are a few that will not get through who otherwise could have done so,” writes Lambart. Discussions are held to try to convince MacCarthy to slow the pace.

The food supply begins to be something of an obsession, with Lambart’s calculations taking up more and more space on the pages of his diary. Lambart also notes that they plan to leave King Col the next day to try to make it to the summit and back in four days.

Team members working a way up through the ice wall above King Col, King Peak towering above (e011313500_s1).

In reality, it takes another 10 days of exhausting climbing with snowshoes and crampons before they finally summit on June 23. The team begins to use ropes to keep team members safe as they tackle bad weather, steep climbs across icefalls, extreme cold and constant fatigue. Morgan, accompanied by Hall, turns back due to poor health. The remaining six continue to push upward, not knowing what lies ahead. While ascending what they think is the summit, Logan wrote the following:

[…] we saw straight off east about 3 miles the real summit of Logan which up to this time, I don’t think any of us had seen before. This was our goal, it was now 4:30 and the weather was holding.

A bit of up and down and a few switchbacks up the final steep, icy slopes—and, finally…

[…] we are on the top of the highest point in the Dominion of Canada. […] We all congratulated Mac and shook hands. […] Carpe ran the Bell and Howell a few seconds, Read took some snaps, but we were reminded by Andy that there was a storm brewing […]

Just 25 minutes is spent savouring their achievement. Almost immediately, the weather begins to close in around them, and the temperature drops rapidly. The sunshine they had enjoyed at the peak disappears as a heavy fog moves in, completely hiding any signs of the trail leading back to their camp. “We are in real peril,” Lambart later notes in his diary. Conditions are deteriorating so rapidly they decide to bivouac on a patch of steep hard snow, where they “were all burrowing like a bunch of rabbits,” to create shelters for the night. Lambart shares a burrow with Read, and gives his heavy coat to Taylor, who is on his own in another burrow. Much to his later misfortune, Lambart overcompensates with four pairs of socks in his boots, restricting the circulation to his toes. He wakes in the middle of the night to try to stamp some feeling back into them, but he will suffer from this miscalculation for the remainder of the expedition and beyond. Several of his toes were amputated later in life.

Two members of the expedition looking out from King Ridge (e011313497_s2).

Although the mountain top remains shrouded in fog the next morning, they have no real choice but to continue in order to locate the trail to find their way back. In the process, both Taylor and Mac walk off cliffs they cannot see, falling several metres each, but without serious injury. Eventually they locate one of the willow poles they had placed every 150 feet as markers on the way up. Nevertheless, the ordeal is not over. The first rope becomes confused and marches in the wrong direction at one point, leaving them several hours behind the others in returning to camp. Lambart begins to hallucinate:

My glasses were dark and the scene ahead was of two figures constantly silhouetted against a dead whiteness where ground and sky was one. A strange imagination possessed me all the while that I could not drive away, namely, the presence of fences and fields and farms with habitations to right and left of us.

A much deserved day of rest follows, but they are back on the trail the day after, which Lambart finds to be “one of the most [difficult] tests of endurance and suffering of the whole trip.” MacCarthy’s obituary for Lambart later revealed that, on what is likely this same day (June 26), Lambart became exhausted in another bout of severe weather, and collapsed face down on their descent to the high-level campsite (5,640 m). He begged MacCarthy to leave him in order to save the others, “a murderous proposal” in MacCarthy’s mind, and Taylor supported him until they stumbled back to camp. Lambart remembers nothing of this.

The remainder of the descent goes relatively smoothly, with the temperature and the weather improving most days, and with the climbers having less equipment and supplies to carry. Additional days of rest are taken from time to time. The team begins abandoning supplies along the route, including Read’s diary, which is never retrieved. On July 1, the first signs of life are joyfully spotted—a bird at Cascade camp and bumble bees and flies at the Advance Base Camp below.

On July 4, their feet finally touch land again. Their relief is quickly dampened by the realization that bears had destroyed not just one, but two, caches of food the team had stowed for their return. Luckily, the next day, they find food that had been left hanging in a tree for them by a colleague. They celebrate that evening, but the next day are back hard at work, constructing rafts to carry them down the Chitina River in order to shorten their trek into town. The raft in which Lambart, Taylor and Read are travelling quickly transports them 72 km downstream to a meadow, from which they begin the final long hike of their journey. The raft conveying MacCarthy, Carpe and Foster follows, but “shot by us in a wider and better channel to our left. Mac held up his hand triumphantly as they went by. This was the last we saw of them.” Lambart, Taylor and Read arrive back in town late at night on July 12, racing each other the last few kilometres in their haste to arrive (in spite of Lambart’s very painful feet). There is no sign of the MacCarthy raft for several worrying days. MacCarthy, Carpe and Foster are finally located on July 15, having overshot their mark, tipped their raft and walked back toward McCarthy until they happened upon a road crew.

Lambart called the expedition “one of the strangest ventures of my life.” The men returned to their homes to much acclaim and publicity, with The New York Times naming Lambart one of the world’s greatest climbers. They wrote their report and printed their photos. Carpe developed and edited his motion picture, to be shown to appreciative audiences in the comfort of heated movie theatres and plush seats.

It would be 25 years before another team would attempt to climb Mount Logan. Today, climbers can fly onto one of the glaciers to avoid the long trek to the base of the massif. It is nevertheless considered to be one of the most challenging climbs in the world.

Our latest Co-Lab challenge allows users to tag images and transcribe entries from Lambart’s diary!

Other LAC resources:

This blog was written by Jill Delaney, Lead Archivist, Photography, in the Specialized Media Section of the Private Archives Division at Library and Archives Canada. Assistance was provided by Angela Code of the Listen Hear our Voices initiative.