By Andrew Horrall

A note to users

Many of these records contain terms that were commonly used during the First World War but are now unacceptable and offensive. The use of these terms by military authorities is evidence of the racism faced by Black Canadian soldiers.

As described in the “Serving despite segregation” blog, No. 2 Construction Battalion was the first and only segregated Canadian Expeditionary Force unit in the First World War. Library and Archives Canada (LAC) has identified and digitized records relating to the unit to make its story, and the individual stories of the men who belonged to it, easy to explore and understand.

Attestation page for Arthur Bright, Canadian Expeditionary Force, RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 1066 – 39

Individual experiences

Archival records contain details about the individuals who served in No. 2 Construction Battalion. Each story is unique and evocative.

You can find the men’s individual personnel records by searching their names, or by entering “No. 2 Construction Battalion” in the “Unit” field in our database. Each file has been completely digitized and includes detailed information about the individual’s life, family and military service.

Friends and families serving together

Personnel records can also tell collective stories. We know that men often joined-up in small groups of family, friends or co-workers in hopes of serving together.

Here are two strategies to find and explore these small groups within the unit. Start by identifying all of the men, by entering “No. 2 Construction Battalion” in the “Unit” field in our database, then:

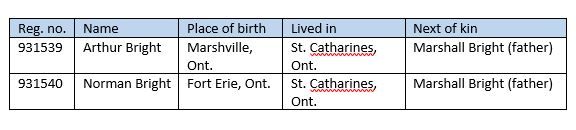

- Sort the list in alphabetical order. You will see that many surnames appear more than once. Open the individual files of men with shared names and look at their places of birth, addresses and next of kin (often a parent) to explore whether and how they were related.

For example, we can see that these two men were brothers:

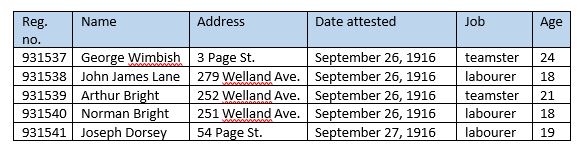

- Sort the list by regimental service number. These were assigned to men in numerical order. Sorting the list in numerical order can recreate the lines of men as they enlisted at a recruiting station. Open the individual files to explore whether a man joined up alone or with a group.

For example, we know that the Bright brothers joined up together because they were assigned sequential service numbers. We also discover that the men with numbers on either side of them—who would have been standing next to them in the recruiting office in 1916—were all of similar age and occupation, and lived within a kilometre of one another in St. Catharines. How did they know each other?

Follow the men in civilian life

To explore Black Canadian history more widely, you can also find out about the civilian lives of many of the men by entering their names in other LAC databases in the “Ancestors Search” section of our website:

- The 1911, 1916 and 1921 Canadian censuses; for example, the 1921 census lists Arthur and Norman Bright living together as lodgers at 3 Brown’s Lane, in downtown Toronto. Neither was married, and they were both working as labourers.

- Passenger lists show when, where and with whom individuals immigrated to Canada.

- Personnel records can open pathways for exploring Canada’s early-20th-century Black community and what it meant to serve in No. 2 Construction Battalion.

Two pages from the personal diary of Captain William “Andrew” White, the unit’s chaplain (e011183038)

Day-to-day life in the unit

Two digitized documents allow you to explore the unit’s daily activities:

- The personal diary of William “Andrew” White, No. 2 Construction Battalion’s chaplain. We believe that this is the only first-hand account written by a member of the unit.

- The War Diary. Units on active service were required to keep a daily account of their activities. While war diaries do not focus on individuals, they describe the events that took place each day.

How the Canadian military managed the unit

LAC has digitized about half of the administrative, organizational and historical records relating to the unit. These documents provide insights into how the Canadian military managed the unit and the men belonging to it.

Digitized resources documenting No. 2 Construction Company held at LAC

Basic information about the unit

Other photographs depicting Black soldiers

- Washing day, September 1916

- Three Black soldiers in a German dug-out captured during the Canadian advance east of Arras

- Black soldiers, who with others, load Canadian Corps Tramways with ammunition, resting

Note that LAC holds many other photos showing Black soldiers, but these cannot be found in a regular search, since that information was not included in the original title.

Recruiting poster

Digitised textual records

-

-

- Canadian Expeditionary Force service files (unit members are identified by “No. 2 Construction Battalion” in the database’s “Unit” field; Users should be aware that the military service files of over 800 men indicate No. 2 Construction Company as their unit, though many of these men never actually served with No. 2 Construction Company. Instead, they served with other CEF units. The reasons for the discrepancy between the information in personnel files and unit files is not entirely clear. It is likely that Canadian military authorities intended for the men to serve with No. 2 Construction Company, but pressing needs caused them to assign the men to other units. In other cases, the war may have ended before individuals could physically join No. 2 Construction Company.)

- Chaplain’s personnel file for Reverend William Andrew White (The digitised file is accessible at Canadiana.org.) RG24, C-1-A, reel T-17604. The file begins at image 2602. Militia and Defence personnel files : T-17604 – Image 2602 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- 2nd Canadian Construction Battalion – nominal roll of officers, non-commissioned officers and men, RG9-II-B-3, Vol. 80

- 2 Construction Battalion, RG9-II-B-9, Vol. 39, file 748

- Part II Daily Orders, No. 2 Canadian Construction Company, RG150-7, Vol. 460

- 2 Construction Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, composed of Black Canadian men, RG24, vol. 4680, file MD12-18-24-1

- Transfer of coloured soldiers to No. 2 Construction Battalion, RG24 vol. 4680, file MD12-18-25-2

- Documents – Selected re: No. 2 Construction Battalion, RG 9 III-C-7, vol 4472, folder 3, file 2, part 3.2

- 2 Construction Battalion, RG24 vol. 1374, file HQ-593-6-1CONST-2

- Establishment – No. 2 Construction Company, RG9-III-B-1-9, Vol. 1608, file E-186-9

- NO 2 Construction Battalion – pay and paysheets, RG24, Vol. 1695, file HQ-683-401-8

- 2 Construction Battalion – Demobilization, RG24 vol. 1695, file HQ-683-401-9

- Organization – including a historical summary of events, RG 9 III-C-7 Vol. 4464, file 9.1

- Correspondence – re: location of depot, RG 9 III-C-7, Vol. 4464, file 9.3

- Construction – No. 2 Company, Canadian Forestry Corps, RG 9 III-C-8, vol. 4516, file 11

- 2 Railway construction draft, RG9-II-B-10, Vol. 16

- Correspondence re: reinforcements – No. 2 Construction Company, RG 9 III-C-7, vol 4464, file 9.2

- Units – No. 2 Construction Company, RG 9 III-A-1, Vol. 81, file 10-9-40

- 2 Construction Battalion – Epidemic of pneumonia, RG24, Vol. 1695, file HQ-683-401-7

- General correspondence, No. 2 Construction Company, RG 9 III-B-1, Vol. 3310, file C-214-43

- Historical Section files, No. 2 Construction Company, R611-362-1-E, RG9-III-D-1

- 2 Construction Company – Badges, RG24, Vol. 1695, file HQ-683-401-4

- 2 Construction Battalion – Battalion fund, RG24, Vol. 1695, file HQ-683-401-6

- List of officers, No. 2 Construction Company – Jura group, RG150-7, Vol. 460

- 2 Construction Battalion, nominal roll, RG9-II-B-10, vol. 51

- 2 Construction Battalion, RG9-II-B-9, vol. 39

- 2 Construction Battalion, RG9-II-B-9, vol. 45

- Sailing list, RG9-II-B-9, vol. 50

- 1st Depot Battalion, Western Ontario Regiment – 43rd Reinforcing Draft, RG9-II-B-9, Vol. 53, file 1310

- After Orders, RG9-II-F-9, vol. 11

- Daily Orders (July–October 1916), RG9-II-F-9, vol. 1079

- Daily Orders (October 1916–March 1917), RG9-II-F-9, vol. 1080

- Daily Orders (October 1916–March 1917), RG9-II-F-9, vol. 1081

- Canadian Record Office in London, RG9-III-B-1, vol. 1147, file R-175-4

- Financial conditions, RG9-III-B-1, vol. 1722, file F-22-13

- Argyll House, London, RG9-III-B-1, vol. 3010, file V-179-33

- 2 Construction Company, RG9-III-C-7, vol. 4464

- 2 Construction Battalion, RG24, vol. 1469, file HQ-600-10-35

- Band, RG24, vol. 1550, file HD-683-124-2

- Mobilization accounts, RG24, vol. 1695, file HQ-683-401-1

- Telephones, RG24, vol. 1695, file HQ-683-401-2

- Clothing and equipment, RG24, vol. 1695, file HQ-683-401-3

- Audit reports, RG24, vol. 1695, file HQ-683-401-5

- Organization of Battalion CEF, coloured battalion, RG24, Vol. 4562, file: MD6-133-17-1

- NO 2 Construction Battalion organization, RG24, Vol. 4393, file MD2-34-7-171

- 2ND Construction Battalion , CEF, RG24, Vol. 4486, file MD4-47-8-1

- Organization – NO 2 Construction Battalion, CEF, RG24, Vol. 4558, file MD6-132-11-1

- Organization – NO 2 Construction Battalion, RG24, Vol. 4599, file MD10-20-10-52

- Mobilization – NO 2 Construction Battalion, CEF, RG24, Vol. 4642, file MD11-99-4-63

- 2 Construction Battalion, RG9-II-B-10, Vol. 45

- Organization of the 2nd Canadian Railway Construction Corps, RG24 Vol. 1469, file HQ-600-10-25 (bac-lac.gc.ca)

- Enlistment of coloured men in the Canadian militia, RG24 volume 1206, file HQ-297-1-21

- 7th Company, Canadian Forestry Corps, RG150, vol 191

- 8th Company, Canadian Forestry Corps, RG150, vol 192

- No 2 railway construction draft organisation. Lieutenant W. Boke – RG24 vol 4399, file MD2-34-7-204

- Returns of coloured men in units, RG 9 III-B-1, Vol. 794, file R-94-2

- Organization of coloured platoons, RG24 Vol. 4387, file MD2-34-7-141

- Dominion Police – Treatment of colored soldiers at Port Arthur, RG13-A-2 vol 229, file 1918-2464

- Governor General – Complaint of coloured man that colour line is drawn in St. John in recruiting, RG13-A-2 vol 199, file 1916-148

- Reinforcements – Gen. [General] file, request for, clerks, stenographers, skilled men, Russians, coloured labour, arriving, cooks, vol. 2, RG9-III-C-8 vol 4508, file 2-72

- Coloured battalion for Alberta, RG24 vol 4739, file MD13-448-1-259

- Disturbance and Riots, RG-9-III, Vol. 1709, file D-3-13, part 6

- Enlistment of Indigenous men for overseas service , WW1, RG24, Vol. 1221, file 593-1-7, parts 1&2

- WAR 1914-1918 – Reports and correspondence regarding recruits and enlisted Indigenous men, RG10, Vol. 6766 file 452-13ESPONDENCE REGARDING RECRUITS AND ENLISTED INDIANS (bac-lac.gc.ca)

-

Courts martial

Digitised records of courts martial involving members of No. 2 Construction Company and other Black men are available on Canadiana.org (Please note that the list below may not be complete)

- Sydney Blackmore, regimental # 213912: RG150, series 8, file 649-B-18466, microfilm T-8654. File begins at image 3289. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 3289 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Arthur Bright, regimental # 931539: RG150, series 8, file 649-B-27441, microfilm T-8658. File begins at image 2596. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 2596 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Garfield Bushfan, regimental # 931149: RG150, series 8, file 649-B-27011, microfilm T-8658. File begins at image 2476. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 2476 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- John Butler, regimental # 931589 RG150, series 8, file 649-B-37429, microfilm T-8661. File begins at image 441. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 441 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Vincent Carvery, regimental # 931395: RG150, series 8, file 649-C-26887, microfilm T-8659. File begins at image 1069. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 1069 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Albert Lindsay Cross, regimental # 455644: RG150, series 8, file 649-C-9221, microfilm T-8653. File begins at image 5165. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 5165 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- William Ambrose Dolman, regimental # 931749: RG150, series 8, file 649-D-8079, microfilm T-8655. File begins at image 5003. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 5003 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Ralph Simpson Freeman, regimental # 931683: RG150, series 8, file 649-F-12706, microfilm T-8665. File begins at image 125. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 125 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Joseph Gilkes, regimental # 931350: RG150, series 8, file 649-G-21050, microfilm T-8667. File begins at image 3494. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 3494 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Carl Grey, regimental # 931660: RG150, series 8, file 649-G-20612, microfilm T-8667. File begins at image 3245. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 3245 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Frederick Henry, regimental # 931026; RG150, series 8, file 649-H-28783, microfilm T-8668. File begins at image 2554. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 2554 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- William Higdon, regimental # 931742: RG150, series 8, file 649-H-30012, microfilm T-8668. File begins at image 3565. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 3565 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- William L. Hogan, regimental # 83666: RG150, series 8, file 649-H-29825, microfilm T-8668. File begins at image 3522. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 3522 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Clinton Hollie, regimental # 931818: RG150, series 8, file 649-H-28402, microfilm T-8668. File begins at image 2178. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 2178 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Lawrence Jackson, regimental # 931351: RG150, series 8, file 649-J-11546, microfilm T-8670. File begins at image 4064. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 4064 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Walter A Johnson, regimental # 931079: RG150, series 8, file 240-J-14, microfilm T-8691. File begins at image: 3439. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 3439 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- George Kelly, regimental # 931830: RG150, series 8, file 649-K-5044, microfilm T-8669. File begins at image 2746. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 2746 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Ralph Middleton, regimental # 931315: RG150, series 8, file 649-M-53878, microfilm T-8683. File begins at image 1599. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 1599 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Russell Miller, regimental # 931530: RG150, series 8, file 649-M-53734, microfilm T-8683. File begins at image 902. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 902 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- John Monroe, regimental # 931715: RG150, series 8, file 649-M-47292, microfilm T-8679. File begins at image 4268. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 4268 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Louis Nealy, regimental # 931629: RG150, series 8, file 649-N-5494, microfilm T-8673. File begins at image 2084. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 2084 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Louis Nealy, regimental # 931629: RG150, series 8, file 649-N-5494, microfilm T-8673. File begins at image 2104. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 2104 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- William Smith, regimental # 931134: RG150, series 8, file 649-S-17749, microfilm T-8685. File begins at image 2785. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 2785 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- John L. Sullivan, regimental # 931736: RG150, series 8, file 649-S-33131, microfilm T-8688. File begins at image 2760. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 2760 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- William John Talbot, regimental # 931021; RG150, series 8, file 649-T-13757, microfilm T-8686. File begins at image 2192. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 2192 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Joseph Trotman, regimental # 888: RG150, series 8, file 649-T-3240, microfilm T-8683. File begins at image 3343. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 3343 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Harry Henry Tynes, regimental # 931044: RG150, series 8, file 649-T-13666, microfilm T-8686. File begins at image 2166. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 2166 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Reggie Tynes, regimental # 931247: RG150, series 8, file 649-T-13818, microfilm T-8686. File begins at image 2360. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 2360 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Earle St Clair, regimental # 684608: RG150, series 8, file 649-S-7774, microfilm T-8682. File begins at image 4691. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 4691 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Earle St Clair, regimental # 684608: RG150, series 8, file 649-S-7774, microfilm T-8682. File begins at image 4714. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 4714 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

- Archer Walton, regimental # 931764: RG150, series 8, file 649-W-27226, microfilm T-8690. File begins at image 2816. Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Can… – Image 2816 – Héritage (canadiana.ca)

Andrew Horrall is an archivist at Library and Archives Canada. He wrote the blog and, with Alexander Comber and Mary Margaret Johnston-Miller, identified records relating to the battalion.