By Beth Greenhorn

By Beth Greenhorn

This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

Who Are the Métis?

The Métis Nation emerged as a distinct people during the course of the 18th and 19th centuries. They are the second largest of the three Indigenous peoples of Canada and are the descendants of First Nations peoples and Europeans involved in the fur trade.

Métis communities are found widely in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and the Northwest Territories, with a smaller number in British Columbia, Ontario, Minnesota, Montana and North Dakota.

Library and Archives Canada (LAC) has a great variety of archival documents pertaining to the Métis Nation (including textual records, photographs, artwork, maps, stamps and sound recordings); however, finding these records can be a challenge.

Challenges in Researching Métis Content in the Art and Photographic Collections

While there are easily identifiable portraits of well-known leaders and politicians, including these portraits of Louis Riel and Gabriel Dumont, images depicting less famous Métis are difficult to find. Original titles betray historical weaknesses when it comes to describing Métis content.

In many cases, the Métis have gone unrecognized or were mistaken for European or First Nations groups—such as the people in this photograph entitled “Chippewa Indians with Red River Carts at Dufferin.”

Chippewa Indians with Red River Carts at [Fort] Dufferin, Manitoba, 1873 (e011156519)

Clad in blankets and wearing feathered headdresses and other hair ornaments, the group on the right appears to belong to the Chippewa (Ojibwe) First Nation, as the title indicates. In contrast, the man on the left is dressed in a European jacket and pants and wears a different style of hat. However, both the man and the group pose in front of Red River carts, which are unique to Métis culture. Given his different style of clothing, coupled with the carts, it is possible that the man was Métis.

In other cases, archival descriptions exemplify colonial views of the “other” culture. Penned over a century ago, the language is often outdated, and the terminology racist, by today’s standards.

A halfcast [Métis] and His Two Wives, 1825-26 (e008299398)

Terms such as “halfcast,” “half-breed,” and “mixed breed” were widely used by the dominant society to describe members of the Métis Nation. This vocabulary is commonly found in older archival records.

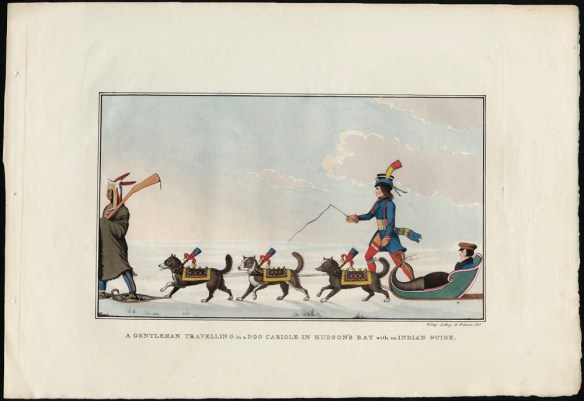

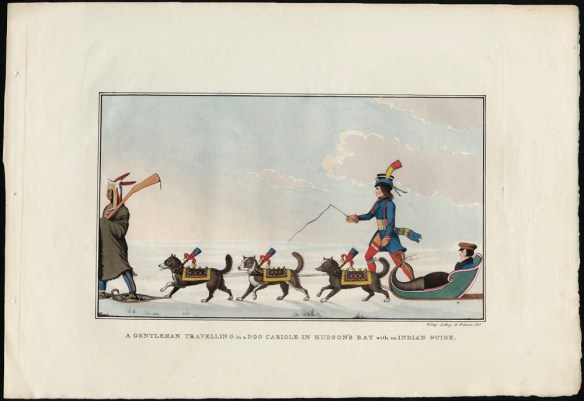

In other instances, descriptions of Métis were completely omitted, as is the case with this lithograph, entitled “A Gentleman travelling in a dog Cariole in Hudson’s Bay with an Indian Guide.”

A Gentleman travelling in a dog Cariole in Hudson’s Bay with an Indian Guide, 1825 (e002291419)

Hiding in Plain Sight: Discovering the Métis in the Collection of Library and Archives Canada

In the fall of 2014, a keyword search for “Métis” in art, photographic, cartographic and stamp records yielded less than 100 documents. LAC has since updated and revised over 1,800 records by adding “Métis” to the titles or descriptive notes in order to make these documents more accessible. In addition to improving existing records, LAC has digitized over 300 new photographic items pertaining to Métis history.

The Hiding in Plain Sight: Discovering the Métis in the Collection of Library and Archives Canada exhibition presents a selection of reproductions of artwork and photographs with Métis content. LAC hopes that the images featured in this exhibition will provide a better understanding of the history of the Métis Nation and that the public will be encouraged to research LAC’s collection.

The exhibition ran from February 11 to April 22, 2016, in the lobby of Library and Archives Canada at 395 Wellington Street, Ottawa.

Additional resources

Beth Greenhorn is a settler living on the unceded, traditional territory of the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg and the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan. She is a Senior Project Manager in the Outreach and Engagement Branch at Library and Archives Canada.