This article contains historical language and content that some may consider offensive, such as language used to refer to racial, ethnic and cultural groups. Please see our historical language advisory for more information.

In early 2002, Library and Archives Canada (LAC) teamed up with the Nunavut Sivuniksavut Training Program and the Government of Nunavut’s Department of Culture, Language, Elders and Youth, to create Project Naming. The goal was to digitize photographs of Inuit from present-day Nunavut in LAC’s photographic collections in order to identify the people depicted in the images. At the time of the launch, LAC expected that the project would be concluded the following year. We never imagined that this initiative would become such a successful and popular project with the public.

To mark the annual National Aboriginal History Month in June 2015, LAC is pleased to announce the launch of Project Naming. While the project still includes communities located in Nunavut, it will be expanded to Inuit living in Inuvialuit (Northwest Territories), Nunavik (northern Quebec) and Nunatsiavut (Labrador), as well as First Nations and Métis communities in the rest of Canada. Project Naming: 2002–2012 will still be available online, but new content will only be added to the new project site.

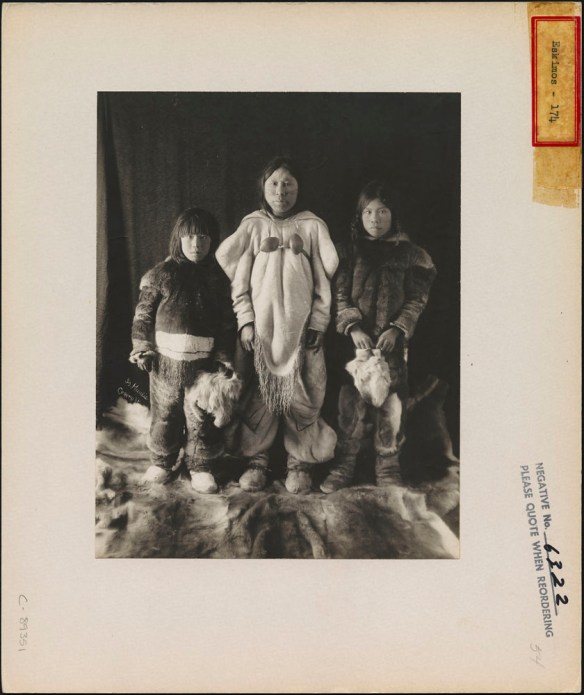

Project Naming: 2002–2012 began with the digitization of 500 photographs from the Richard Harrington fonds. Since then, LAC has digitized approximately 8,000 photographs from many different government departments and private collections. Thanks to the enthusiasm and support from Inuit and non-Inuit researchers, nearly one-quarter of the individuals, activities or events portrayed in the images have been identified, and this information along with the images is now available in the database.

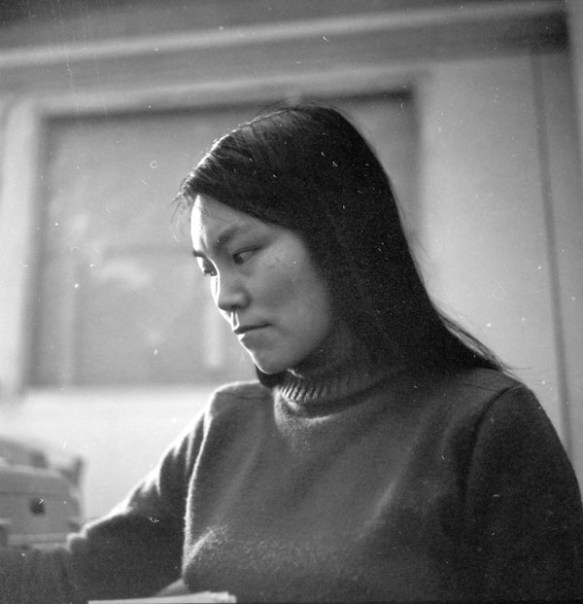

Over the years, LAC has received many wonderful stories and photographs from members of the public who have reconnected with their family and friends through the photographs. Among these was a photograph shared by the Kitikmeot Heritage Society that organized several community slide shows during the winter of 2011. Mona Tigitkok, an Elder from Kugluktuk, discovered her photograph as a young woman during one of these gatherings.

Mona Tigitkok posing with a picture of herself taken more than 50 years ago, Kugluktuk, Nunavut, February 2011. Credit: Kitikmeot Heritage Society.

Author and historian, Deborah Kigjugalik Webster, has used Project Naming, both personally and professionally. In her words:

I was first introduced to Project Naming a few years ago through my work in the Inuit heritage field, but there is also a personal connection for me—the database allows people to search by communities in Nunavut so I’ve discovered photographs of relatives and community members.

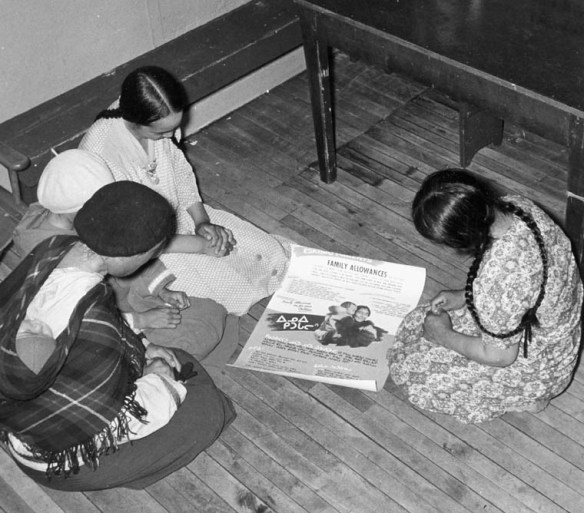

It was not uncommon in the past for photographers not to name the subjects of images. Often photo captions were simply “group of Eskimos” or “native woman” and so on. One afternoon, over tea, I showed some of the photographs from the Project Naming database to my mother, Sally Qimmiu’naaq Webster, and we were able to add a few names to faces from our home community of Baker Lake (Qamanittuaq). I felt a sense of satisfaction in identifying unnamed individuals in photographs and providing names to replace nondescript captions provided by the photographer. In a sense, when we do this we are reclaiming our heritage.

Photograph of the late Betty Natsialuk Hughson (identified by her relative Sally Qimmiu’naaq Webster). Taken in Baker Lake (Qamanittuaq), Nunavut, 1969 (MIKAN 4203863)

Project Naming allows people to not only identify individuals in images, but to add information including corrections to the spelling of names in an online form. It is well worth checking out the database, especially with an Elder, because seeing the image opens up discussion.

As part of my work I manage a Facebook page Inuit RCMP Special Constables from Nunavut to acknowledge the contributions of our Inuit Specials and pay tribute to them. Last year I posted a portrait photograph that I found on the Project Naming database of Jimmy Gibbons, taken in Arviat in 1946. Special Constable Gibbons was a remarkable man who joined the RCMP in 1936 and retired to a pension in 1965. This post was met with many enthusiastic likes, shares and comments from S/Cst. Gibbons’ descendants saying that he was their father, uncle or great-grandfather. Some people also simply said “thank you.” Shelley Ann Voisey Atatsiaq proudly commented, “No wonder I wrote earlier that I highly respect the R.C.M.P. I’ve got some R.C.M.P-ness in my blood. Thank you for sharing!”

Jimmy Gibbons, Royal Canadian Mounted Police Special Constable, Arviat, Nunavut, August 1, 1946 (MIKAN 4805042)

For more information about the history of the project, read the article Project Naming / Un visage, un nom, International Preservation News, No. 61, December 2013, pp. 20–24.

As with the first phase of the project, LAC wants to hear from you through The Naming Continues form.