By Dalton Campbell

Library and Archives Canada (LAC) has a collection of approximately 300 labour union charters dating from the 1880s to the 1980s. A sample of the charters has been digitized: the images are available through Collection Search.

These charters were formal documents granted by unions to the locals when they were officially accepted into the union. The charters in the LAC collection can also tell us a lot about the unions, their membership, Canadian workers and work life in the twentieth century.

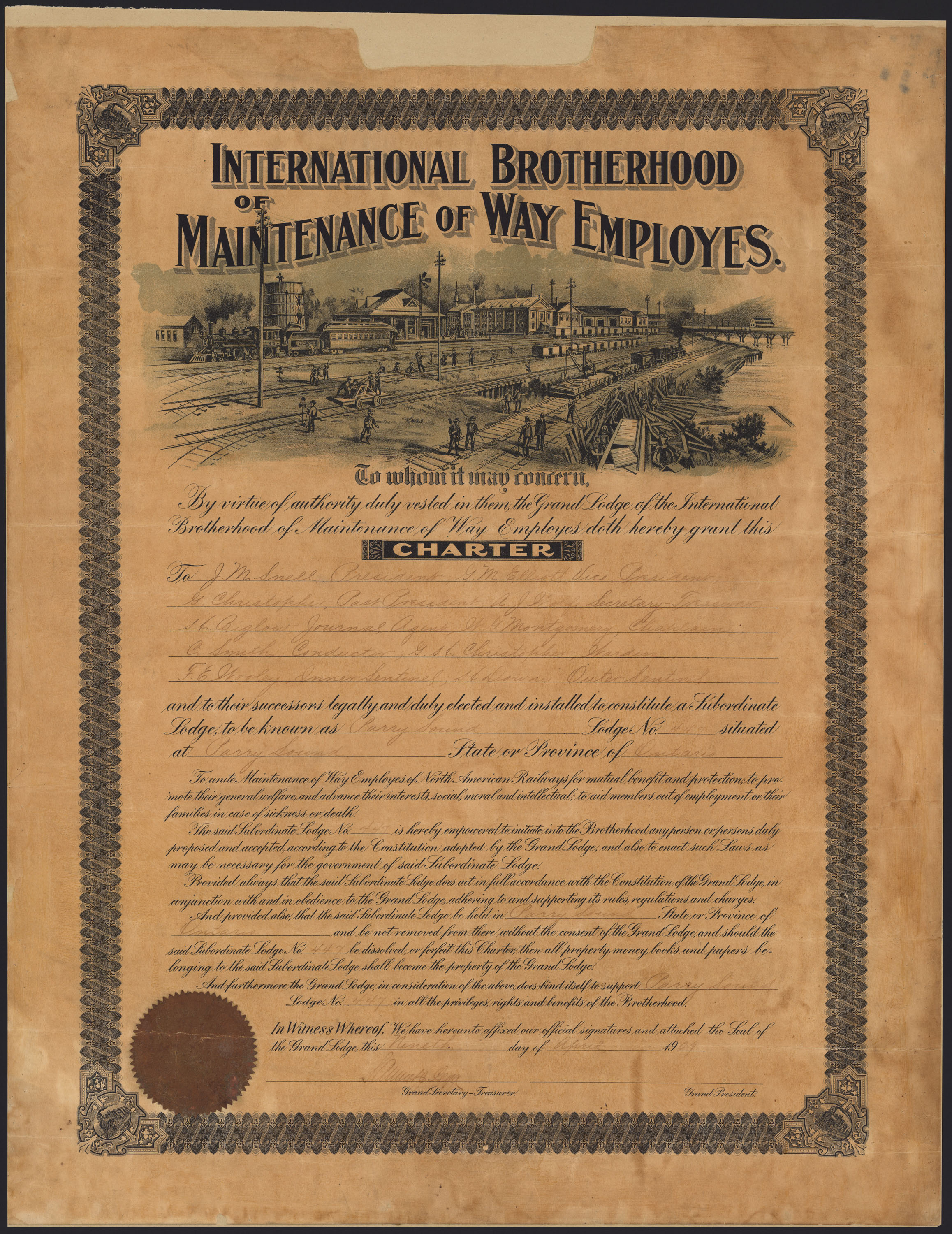

For example, the Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employes charter features a detailed illustration showing the range of jobs done by its members, including tending to trains in the yard, inspecting and maintaining the rails, signals, water towers and buildings, as well as clearing the wreckage of rail cars.

Charter granted by the International Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employes to the Parry Sound Lodge no. 447, Parry Sound, Ontario, April 1909. (e011893857)

This charter, like many of the charters in the LAC collection, includes the names of the members of the local, potentially making charters a small piece of documentation in family history research. Some charters are also a window into social history. For instance, the members’ names listed in the Canadian Congress of Labour (CCL) charters show the industries and companies where women were employed in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s.

Illustrations of union members at work and their workplaces are a common theme in the charters. The Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners charter uses a series of illustrations of workers in different workplaces as well as illustrations of workers receiving benefits from their union.

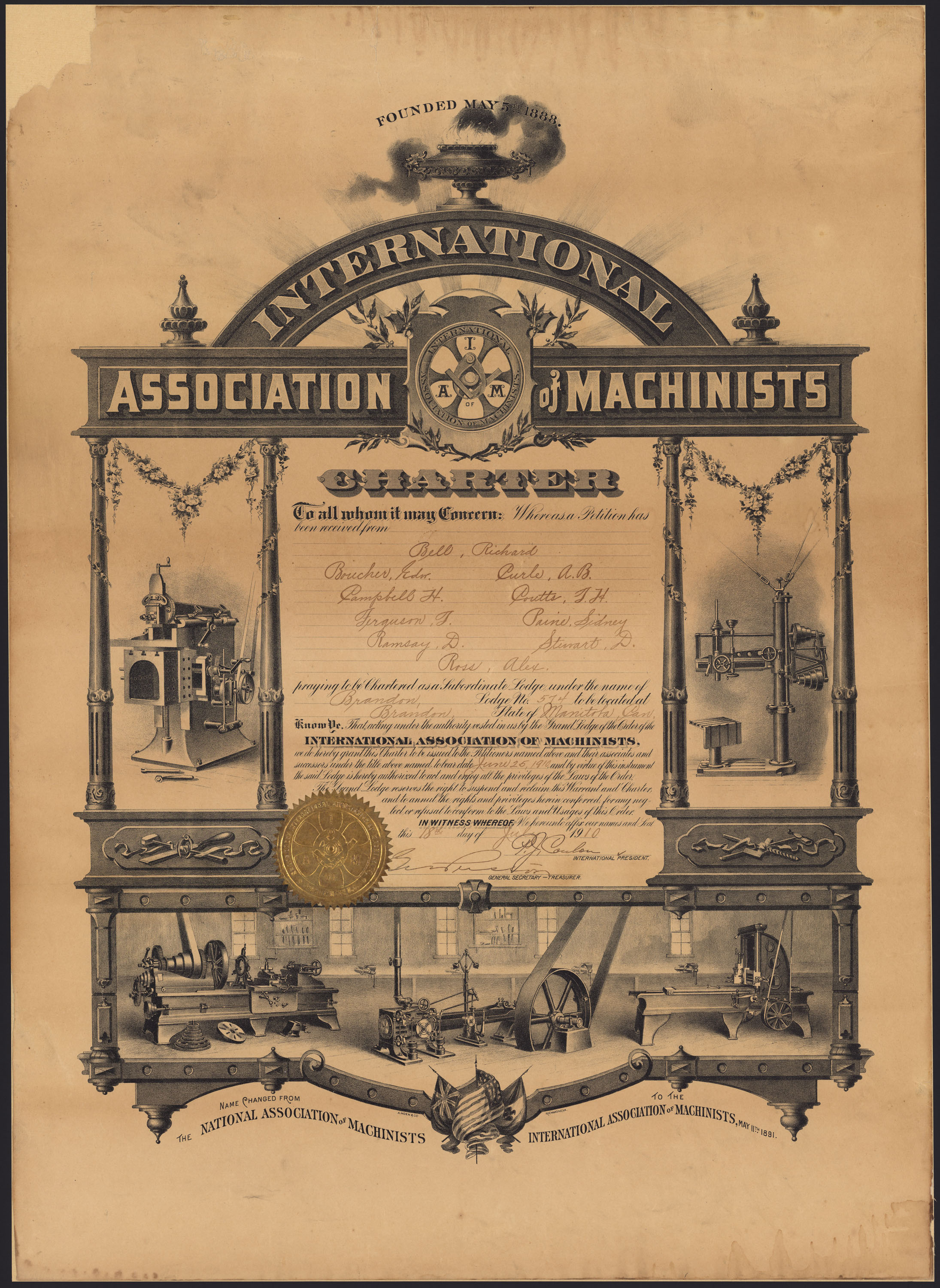

The International Association of Machinists charter features a workshop scene without any workers, showing only a lathe, drills, workbenches, clamps and hand tools—leaving it to the viewer to picture the tasks performed at each workstation.

Charter granted by the International Association of Machinists (IAM) to Local 574, Brandon, Manitoba, July 1910. (e011893856)

This charter is very different from the charter granted by the same union 20 years earlier, in 1890, to Pioneer Lodge no. 103, Stratford, Ontario. (See: MIKAN 4970006)

The International Chemical Workers Union used the same theme, featuring the beakers, flasks and glass tubing of a laboratory in the foreground with an external view of a chemical plant in the background. The Brotherhood of Painters, Decorators and Paperhangers took a different approach, using text to list the many trades and industries in which the union membership worked.

Many of the charters in the LAC labour collection rely primarily on text, with few or no illustrations. Some feature a small illustration such as the union’s seal or logo, something associated with the industry, or something representative of union membership in general (such as a handshake). In some cases, illustrations of figures such as Benjamin Franklin or a bald eagle clearly show that the Canadian local was part of a U.S.-based international parent union.

Some of the text-only charters use detailed, colourful and eye-catching lettering, as seen in those from the International Typographical Union and the Hotel and Restaurant International Employees’ Association.

Charter granted by the International Typographical Union (ITU) to the Ottawa Typographical Union, Local 102, Ottawa, Ontario, 1883. The charter states the local was in “Ottawa, Canada West;” Canada West had been renamed Ontario in 1867. (e011893860)

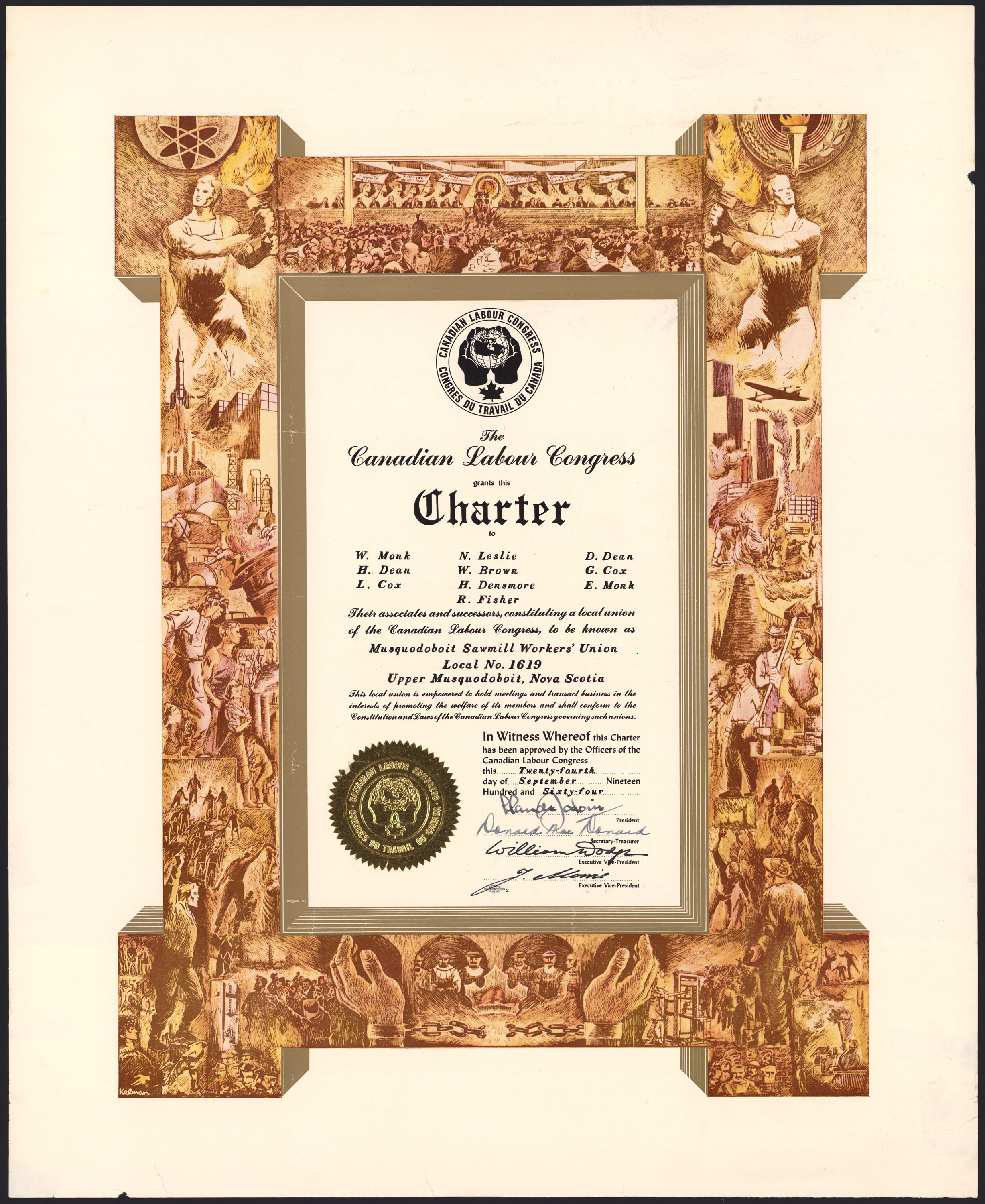

The most ambitious and arguably most artistically successful charter in the collection is the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) charter, designed by CLC artist Harry Kelman in the 1950s.

Charter granted by the Canadian Labour Congress to the Musquodoboit Sawmill Workers’ Union, CLC Local 1619, Upper Musquodoboit, Nova Scotia, September 1964. (e011893866)

For a detailed explanation of the illustrations in this charter, please consult: MIKAN 2629372.

The CLC also printed this same charter in a different colour scheme: see, for example, Buckingham Plastic Workers’ Union, Local 1551, Buckingham, Quebec. (e011537977)

The illustration in this charter uses realistic figures and symbols to show a brief history of the Canadian labour movement from the nineteenth century to the 1950s. The bottom panel shows working conditions in the nineteenth century. This was the time when, as historian Desmond Morton wrote, there was the “harsh reality of […] appalling rates of sickness, death and injury” in lumber camp bunkhouses, high rates of death in mining, and an “appalling toll of life and limb, often of young children” in factories and mills.

The vertical panels on the left and right of the charter show life in the twentieth century. The workers step into the light to work in an industrialized Canada, manufacturing cars and refining minerals; they then move into the “space age,” where they are building and operating rockets, aircraft, skyscrapers and telecommunication systems. The horizontal panel at the top shows the founding convention of the CLC in 1956. The CLC charter has an optimistic tone. The workers contribute to economic and technological progress and they share in the benefits. The present is bright and the future will be brighter.

Looking at the LAC collection of charters, it’s also interesting to look at what is under the surface and what that can show us of life in the early- to mid-twentieth century.

The workers depicted in the charters have little or no safety equipment, reflecting the standards of the era. The charters feature few images of desk workers, but it seems that only a small percentage of locals in the early to mid-twentieth century represented clerical and other office workers.

Additionally, the flag shown in the charters of the Machinists, the Brotherhood of Painters and other unions was the old Red Ensign. The unions designed these charters years, and sometimes decades, before the current Canadian flag was adopted in 1965.

The smokestacks in the CLC charter are symbols of progress and wealth and not pollution and environmental damage.

As well, the workers depicted in the charters are almost entirely white men. The CLC charter includes a few women workers; the only other depictions of women in charters are as customers or grieving widows. Racialized workers and workers with disabilities are absent from the illustrations.

According to files in the labour fonds, it appears that many of the charters in the LAC collection were returned to the union, and later donated to LAC, when the local dissolved, the membership of the local voted to move to another union, the union merged into another union or the union asked the local to leave the union.

In some cases, locals in good standing sometimes had old charters in their offices. In 1972, the CLC asked its locals to return any old charters to the head office and then the CLC would in turn donate the old charters to LAC.

Originally created as official documents to mark the affiliation between locals and the unions, these charters also fostered a sense of shared identity and membership while providing a visually appealing addition to the offices and meeting rooms of the locals. Today, the charters have a secondary value as a window into the unions, workers, workplaces and work life of the twentieth century—and as an introduction to LAC’s collection of labour archives.

Further research:

- Charters of the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) (MIKAN 107969)

- The Canadian Labour Congress Charter. Development and interpretation of its imagery (MIKAN 2629372)

- Charters of the Canadian Congress of Labour (CCL) (MIKAN 107924)

- Charters of the All-Canadian Congress of Labour (ACCL) (MIKAN 107906)

- Charters of the Trades and Labor Congress (TLC) (MIKAN 107903)

- Charters of the International Association of Machinists (IAM) (MIKAN 191424)

- Charters of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE) (MIKAN 130940)

Published sources on Canadian labour history:

- Titles available to read online:

- Carmela Patrias and Larry Savage, Union power: solidarity and struggle in Niagara (OCLC 806034399)

- David Frank and Nicole Lang, Labour landmarks in New Brunswick = Lieux historiques ouvriers au Nouveau-Brunswick (OCLC 956657952)

- Eric Strikwerda, The wages of relief: cities and the unemployed in prairie Canada, 1929-39 (OCLC 847132332)

- Other titles:

- Desmond Morton, Working people: an illustrated history of the Canadian labour movement (OCLC 154782615)

- Steven C. High, One job town: work, belonging, and betrayal in Northern Ontario (OCLC 1035230411)

Dalton Campbell is an archivist in the Science, Environment and Economy section of the Private Archives Division at Library and Archives Canada.

![A black-and-white photograph of a group of people marching in the street, carrying a banner that reads “Travailleurs et Travailleuses du Textile, CSD [Centrale des syndicats démocratiques], Usine de Montmorency” [Textile workers, CSD (Congress of Democratic Trade Unions), Montmorency factory].](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/e011213559-v8.jpg?w=584)