By François Larivée

The CIL name is a commercial brand that immediately evokes something in the collective consciousness, namely paint. However, for those who explore the history behind this well-known brand, it probably comes as a surprise to learn that CIL’s origins are in the manufacturing of explosives and munitions.

CIL advertising billboard on Monkland Boulevard, Ville LaSalle, Quebec, circa 1950 (a069072)

Explosive beginnings

The origins of CIL can be traced back to 1862, before Confederation. That year, the Hamilton Powder Company was formed in Hamilton, Ontario. The company specialized in the production of black powder, which was then used as an explosive for a variety of purposes, particularly for railway construction, a booming industry at the time.

The Hamilton Powder Company’s activities culminated in 1877, when it was awarded a major contract to participate in the construction of the national railway linking Eastern Canada and British Columbia. (This railway was famously a condition set by British Columbia for joining Confederation.) The black powder produced by the company was then used to enable the railway’s perilous crossing of the Rocky Mountains in 1884 and 1885.

Following its expansion, the Hamilton Powder Company moved its head office to Montréal. It was also near Montréal, in Belœil, that from 1878 onward, the company developed what would become its main explosives production site.

In 1910, it merged with six other Canadian companies, most of which also specialized in the production of explosives. Together, they formed a new company: the Canadian Explosives Company (CXL). Although explosives remained the bulk of the company’s production, new activities were added, including the manufacture of chemical products and munitions.

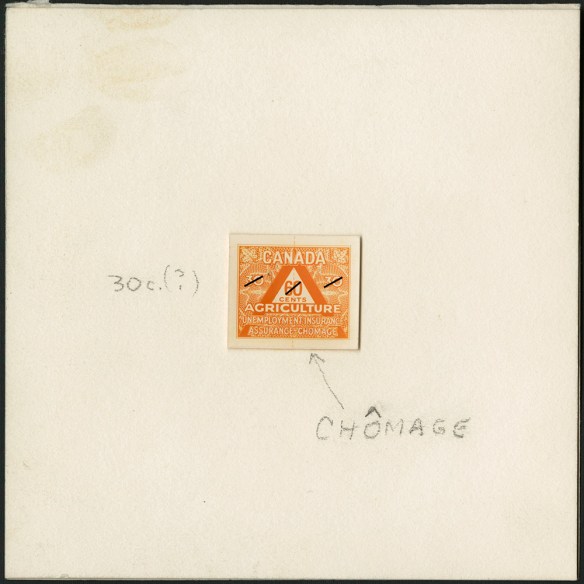

One of the companies involved in the merger, the Dominion Cartridge Company, already specialized in the manufacture of munitions, particularly rifle cartridges (used mainly for hunting). It was founded in Brownsburg, Quebec, in 1886 by two Americans—Arthur Howard and Thomas Brainerd—and Canadian John Abbott, who would later become the country’s third prime minister. In 2017, Library and Archives Canada acquired a significant portion of CIL’s archival holdings relating to its Brownsburg plant.

World wars and munitions

During the first half of the 20th century, the company produced more and more munitions. Indeed, as a consequence of the two world wars, the demand for military ammunition in particular increased sharply.

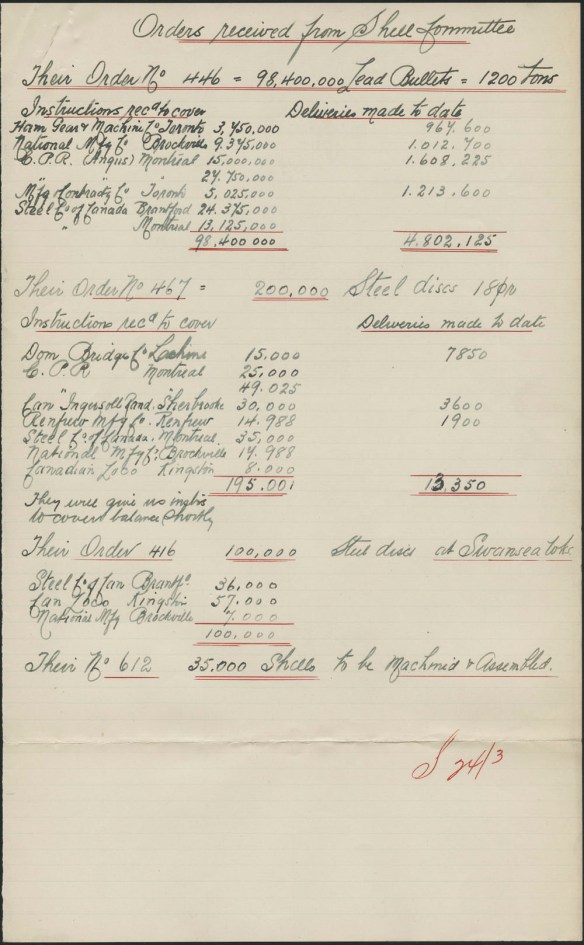

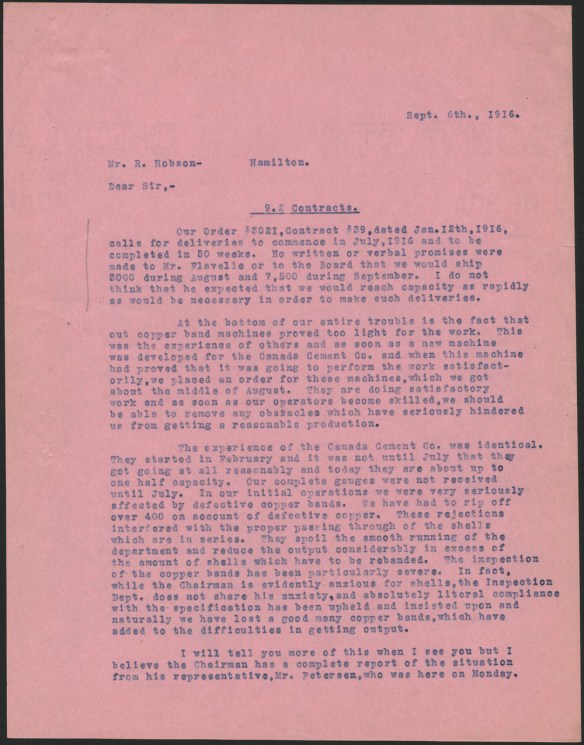

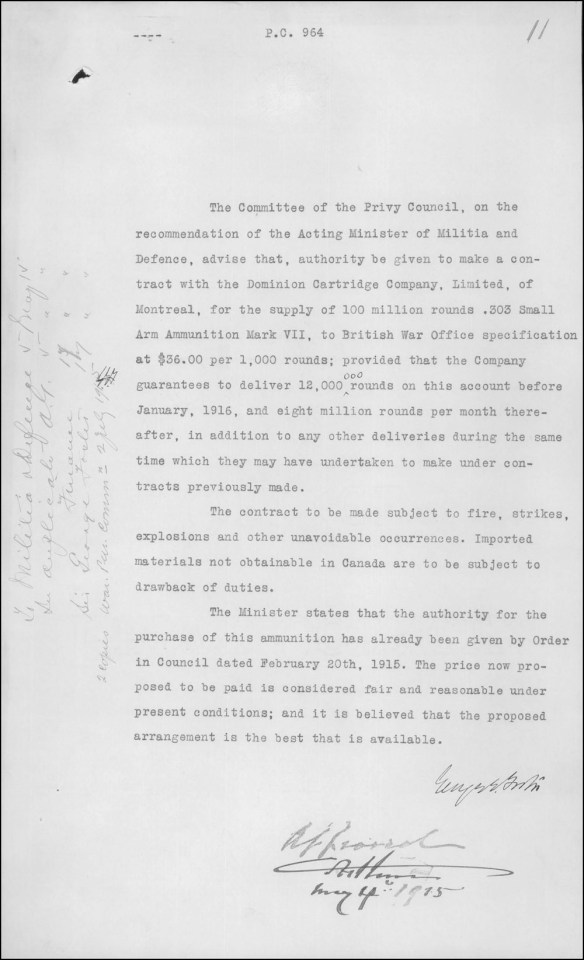

As early as 1915, the Dominion Arsenal (responsible for the production of military ammunition in Canada) could not meet the demand on its own. The Canadian government therefore sought the help of Dominion Cartridge, then one of the largest private companies in this sector. The company thus obtained major contracts to produce military ammunition.

Privy Council Office Order-in-Council approving a contract with the Dominion Cartridge Company for the production of munitions, May 1915 (e010916133)

To reflect the gradual diversification of its operations, the company changed its name to Canadian Industries Limited (CIL) in 1927.

After the outbreak of the Second World War, CIL further increased its production of munitions. In 1939, in partnership with the Crown, it established a subsidiary company dedicated exclusively to this sector of activity, Defence Industries Limited (DIL). The Crown owned the factories and equipment, but it delegated the management of operations to CIL. The Crown also provided CIL with the funds to operate the plants, although it did not purchase their production.

Given the considerable ammunition requirements of the Allied forces, DIL expanded rapidly. It opened many factories: in Ontario, in Pickering (Ajax), Windsor, Nobel and Cornwall; in Quebec, in Montréal, Brownsburg, Verdun, Saint-Paul-l’Hermite (Cherrier plant), Sainte-Thérèse (Bouchard plant), Belœil and Shawinigan; and in Manitoba, in Winnipeg.

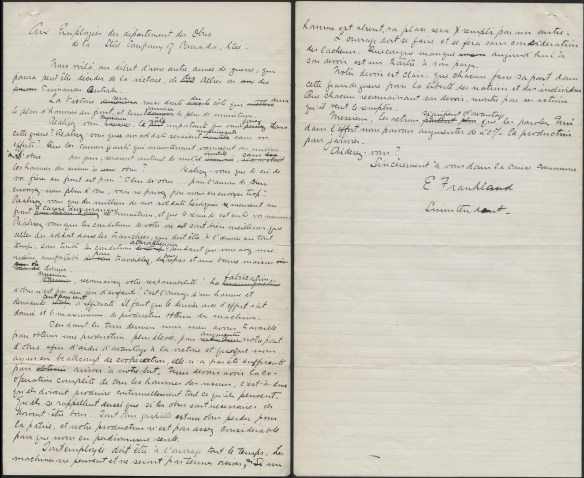

Some occupied huge sites, turning DIL into one of the largest industrial complexes of the time. In 1943, at the peak of its activity, it employed more than 32,000 people, the vast majority of whom were women.

Edna Poirier, an employee of Defence Industries Limited, presents the Honourable C.D. Howe with the hundred-millionth projectile manufactured in the Cherrier plant, Saint-Paul-l’Hermite, Quebec, September 1944 (e000762462)

Workers leaving the Cherrier plant of Defence Industries Limited to take the train, Saint-Paul-l’Hermite, Quebec, June 1944 (e000762822)

New products and a centennial

After the Second World War, CIL gradually reduced its production of munitions, which it abandoned definitively in 1976 to concentrate on chemical and synthetic products, agricultural fertilizers, and paints. It then began to invest a large part of its operating budget into the research and development of new products. Its central research laboratory, which was established in 1916 near the Belœil plant, grew in size, as evidenced by a large part of CIL’s archival holdings held at Library and Archives Canada.

The development of the explosives factory and laboratory in the Belœil region led to the creation of a brand-new town in 1917: McMasterville, named after William McMaster, first chairman of the Canadian Explosives Company in 1910.

Worker pouring liquid nylon from an autoclave, Canadian Industries Limited, Kingston, Ontario, circa 1960 (e011051701)

Bagging of chemical fertilizer at the Canadian Industries Limited plant, Halifax, Nova Scotia, circa 1960 (e010996324)

Although CIL was diversifying its operations, the production of explosives remained the company’s main driver of growth and profitability. These explosives were used in many major ventures, including mining projects in Sudbury, Elliot Lake, Thompson, Matagami and Murdochville, and hydroelectric projects in Manicouagan, Niagara and Churchill Falls. They were also used in the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway and the Trans-Canada Highway.

To mark its centennial in 1962, the company had a major building constructed in downtown Montréal: the CIL House (now the Telus Tower). The work was carried out between 1960 and 1962 and is a testament to CIL’s growth.

Around the same time, the company bought a heritage house in Old Montréal, which it restored and named the CIL Centennial House initially, then the Del Vecchio House (in honour of the man who had it built). The company periodically exhibited collection pieces there from its weapons and ammunition museum in Brownsburg.

The company faded, but the brand endures

In 1981, CIL moved its head office from Montréal to Toronto. Its central research laboratory was moved from McMasterville to Mississauga. The McMasterville explosives factory remained in operation, despite the many workplace accidents—some fatal—that happened there. It gradually reduced its production before closing for good in 2000.

However, CIL’s heyday had long since passed. From 1988 onward, the company had just been a subsidiary of the British chemical company ICI (which was itself acquired by the Dutch company AkzoNobel in 2008).

But to complete the story, in 2012, the American company PPG purchased AkzoNobel’s coatings and paint production division, thereby acquiring the well-known CIL paint brand, which still exists today.

Related resources

- Canadian Industries Limited fonds

- National Film Board fonds

- Hayward Studios fonds

- Malak Karsh fonds

- Durflinger, Serge. Fighting from Home: The Second World War in Verdun, Quebec. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006. 296 p.

François Larivée is an archivist in the Science, Environment and Economy Section of the Archives Branch.

![A black-and-white photograph of a group of people marching in the street, carrying a banner that reads “Travailleurs et Travailleuses du Textile, CSD [Centrale des syndicats démocratiques], Usine de Montmorency” [Textile workers, CSD (Congress of Democratic Trade Unions), Montmorency factory].](https://thediscoverblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/e011213559-v8.jpg?w=584)