By Dalton Campbell

Labour Day first became a national holiday 130 years ago in 1894. In April of that year, labour leaders met with Prime Minister Sir John Sparrow David Thompson. They made a number of demands; he agreed to only one, saying that he would work towards establishing Labour Day. By summer, legislation was enacted to make the first Monday of September a statutory holiday.

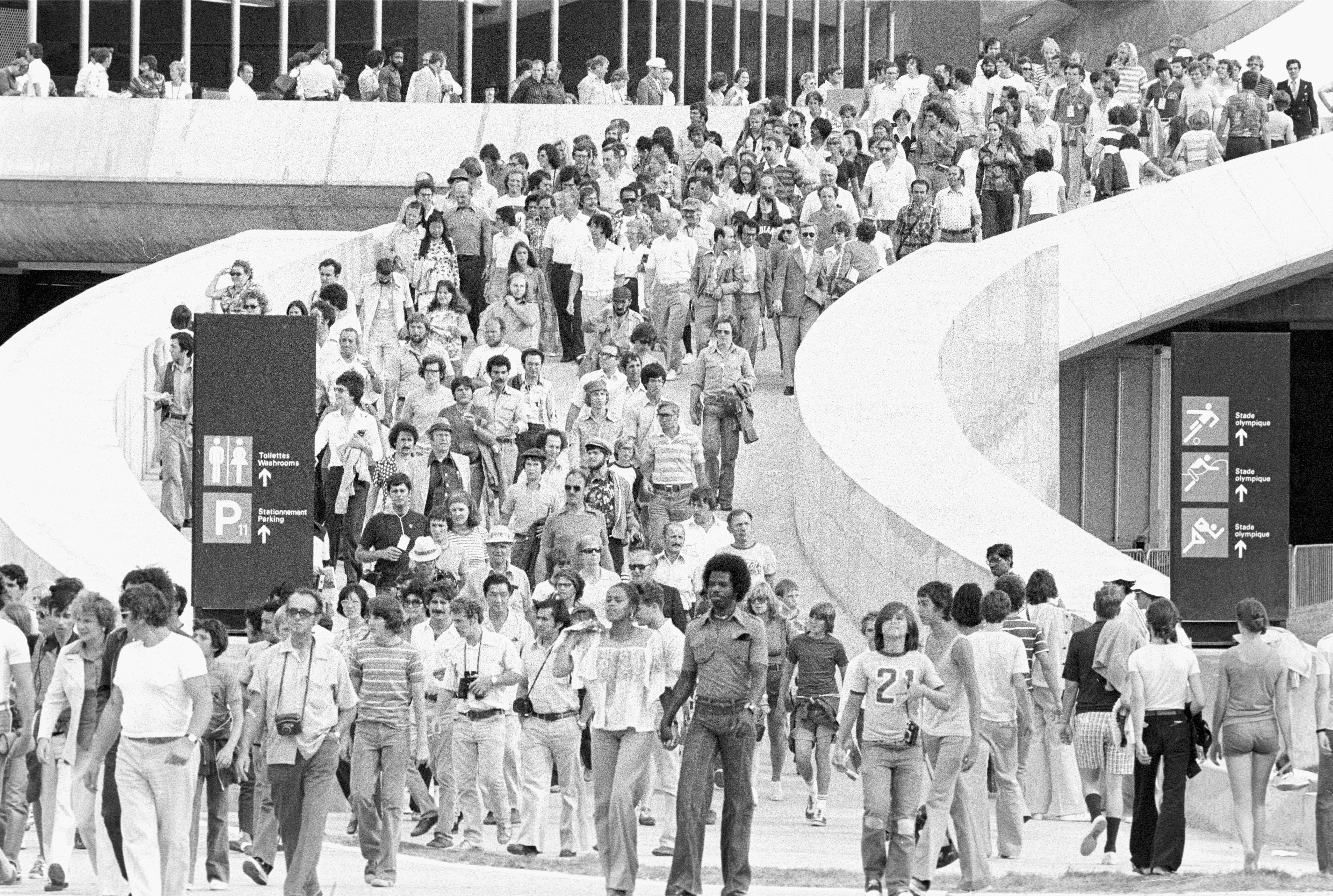

Labour Day parade, Main Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba, 1895. Sir William Van Horne fonds (e011367824-005). Desmond Morton writes that in the 19th century, “[p]rocessions, with floats, banners, and regalia, were a form of mass entertainment and a demonstration of order and respectability rather than militancy.”

Labour Day parade, Front Street, Belleville, Ontario, 1913. Topley Studio fonds (a010532).

A national day celebrating labour was not a new idea in 1894. The holiday had been recommended five years earlier in the final report (1889) of the Royal Commission on Relations of Labor and Capital in Canada.

The Commission’s recommendations were not implemented. However, the report still represents a significant document in Canadian labour history. It included testimonies from workers and their family members discussing the unsafe working conditions, long work hours, low wages, workplace fines, discipline, child labour and other problems. Factories in 19th century Canada were, as Jason Russell describes, “dark spaces with machinery that lacked guards to protect the workers operating them. The factories were places of boilers, steam engines and open flywheels […] and achieving even a 10-hour workday was a major objective for craft unions.”

Before Labour Day was proclaimed, local labour day celebrations had been, as Craig Heron and Steven Penfold write, “an established event on the local holiday calendar in several cities and towns.” There was a long tradition of people taking over public spaces for parades and festivals throughout the 19th century in Canada; in the 1880s, “unionized craft workers in the country took over the traditions [of parades] and made up a new one.”

Knights of Labor procession, King Street, Hamilton, Ontario, 1880s. Edward McCann collection (a103086). Originally from the United States, the Knights of Labor entered Canada when they became established in Hamilton in 1881. They quickly expanded to become one of the most important labour organizations in 19th century Canada.

Miners in Nova Scotia organized what appears to have been the first local labour holiday in 1880, followed by Toronto in 1882 and then by Hamilton and Oshawa (1883), Montreal (1886), St. Catharines (1887), Halifax (1888), Ottawa and Vancouver (1890) and London (1892).

The Trades Union Advocate, a weekly labour newspaper, described the July 1882 labour parade in Toronto in detail.

The parade featured workers from various craft unions with small workstations set up on flatbed wagons. As they went through the city, they presented their work to the crowds: the lithographers printed leaflets and pictures, the cigar makers rolled tobacco “with remarkable dexterity and nimbleness,” the seafarers had equipped their trailer as a ship and so on. The parade included dignitaries, union members marching on foot holding banners and signs and a dozen marching bands scattered among the floats. The Toronto Globe reported that at least 3 000 people marched in the parade and 50 000 watched from the sidewalks.

In addition to the Trades Union Advocate, the LAC labour collection also has a number of Labour Day photographs: some of these images are included here and others are available in this LAC Flickr album, with all of them being available through Collection Search.

Labour leader and social activist Madeleine Parent at the microphone. Labour Day, Valleyfield, Quebec, 1948. Madeleine Parent and R. Kent Rowley fonds (a120397).

The LAC labour collection also includes approximately 50 Labour Day messages from the 1930s to the 1970s by labour leaders A.R. Mosher, Pat Conroy, Jim MacDonald, Donald MacDonald, Jean-Claude Parrot and others. The messages touch on universal themes: the gains of labour unions, the need to organize more workplaces and the vital role of workers to corporate profits, production and the economy. Each year’s message also touched on contemporary events, making the speeches a small historical snapshot of that year. The perennial message, however, was one of support for workers. In 1966, Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) president Claude Jodoin captured this in words that still resonate in the 21st century, “Trade unions have devoted a major part of their efforts to obtaining for workers the right to leisure and relaxed enjoyment of the fruits of their labour.” Labour Day, a holiday enjoyed today by millions of Canadians, is one of the results of those efforts.

Further research:

- Trades Union Advocate (MIKAN 107136)

- Labour Day messages (digitized copies)

- Sir John Thompson fonds (MIKAN 104457)

- Madeleine Parent and R. Kent Rowley fonds (MIKAN 105430)

Published sources:

- Craig Heron and Steven Penfold, The workers’ festival: a history of Labour Day in Canada (OCLC 58545284)

- Jason Russell, Canada, a working history (OCLC 1121293856)

- Desmond Morton, Working people: an illustrated history of the Canadian labour movement (OCLC 154782615)

- Report of the Royal Commission on the Relations of Labor and Capital in Canada (OCLC 1006920421, Government of Canada publications publications.gc.ca 472984)

- Greg Kealey, ed., Canada investigates industrialism: the Royal Commission on the Relations of Labor and Capital, 1889 (OCLC 300947831)

Dalton Campbell is an archivist in the Science, Environment and Economy section of the Private Archives Division at Library and Archives Canada.